You’re sitting at a red light. Your left foot is buried in the floorboard, holding back a heavy spring. Your right hand rests on a plastic or leather knob. When the light turns green, a series of mechanical handshakes happens within milliseconds. If you've ever looked at a diagram of manual transmission components, it looks like a nightmare of spinning clocks. But honestly? It’s a masterpiece of simple physics that we’ve somehow convinced ourselves is "voodoo."

Most people think the gears are just sliding back and forth like LEGO bricks. They aren't. In a modern constant-mesh gearbox, those gears are always touching. Every single one of them. They’re spinning at different speeds, just waiting for you to tell them it’s their turn to carry the load. If you actually tried to slide moving gears into each other while driving, you’d hear a sound like a woodchipper eating a silverware drawer.

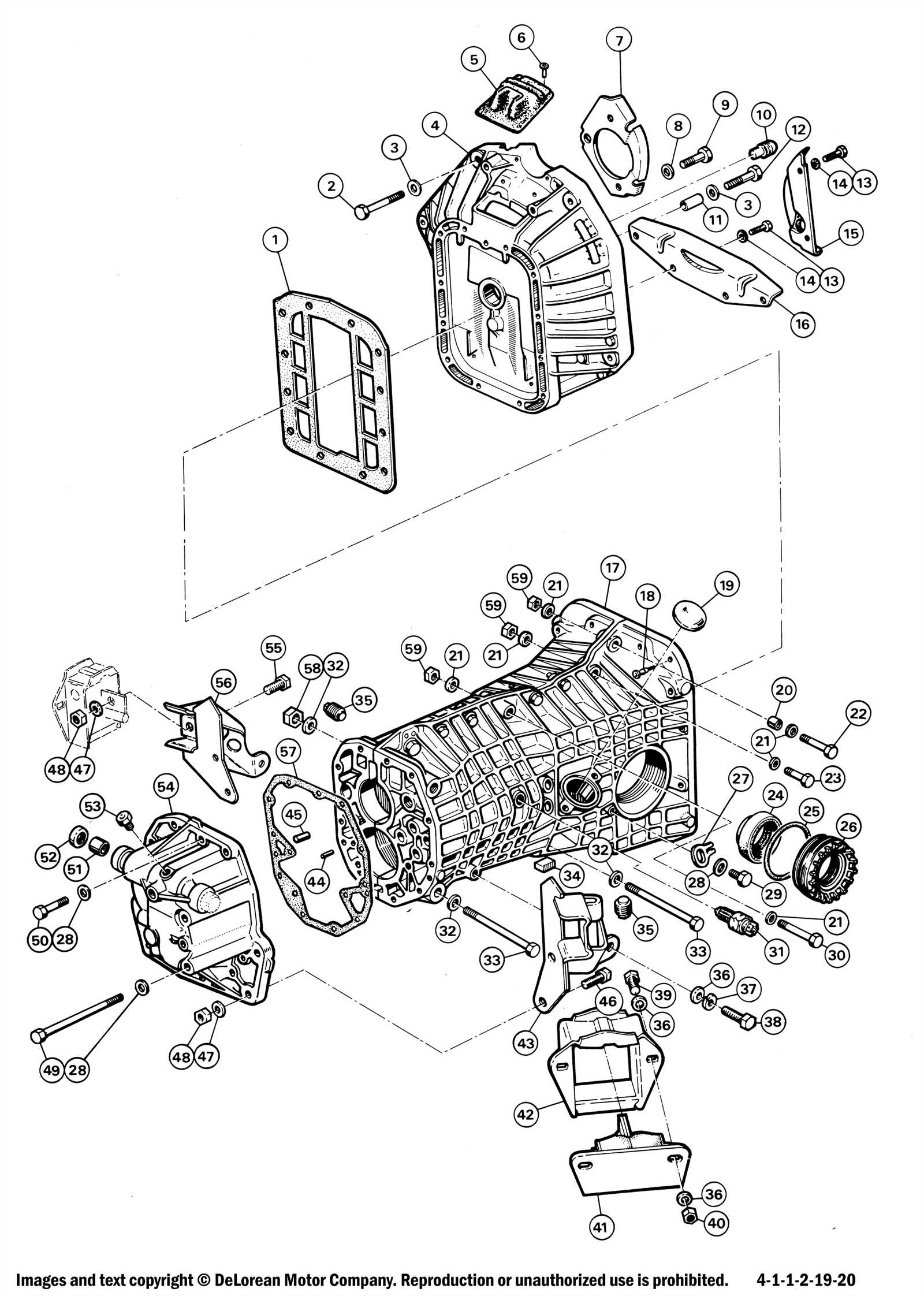

The Three Shafts That Do All the Work

To understand any diagram of manual transmission layouts, you have to visualize three distinct paths for power. First, there’s the input shaft. This is the "bridge" from your engine. It’s got one job: spin at whatever speed the engine is spinning. Then you have the countershaft (or layshaft). This is the middleman. It sits at the bottom of the casing, bathed in heavy oil, and it receives power from the input shaft to distribute it to all the gear sets.

Then comes the output shaft. This is where the magic—and the confusion—happens.

The output shaft holds the gears you actually select. But here’s the kicker: those gears aren't actually "fixed" to the shaft. They sit on bearings and spin freely. You could spin the first gear with your finger while the car is in neutral and the shaft itself wouldn't move an inch. The diagram of manual transmission internals often shows these as "floating" elements, and that’s exactly what they are until you move the shifter.

📖 Related: Why You Should Understand How to Create Fake News Article Templates for Digital Literacy

Why You Don't Hear Grinding Every Time You Shift

You’ve probably heard of "synchros." If you haven't, they are the unsung heroes of your commute. Back in the day—think early 20th century—drivers had to "double-clutch." You had to manually rev the engine to match the speed of the gear you wanted to enter. If you missed the mark, you'd grind the dog teeth. It was an art form.

Today, we use synchronizers.

Imagine a brass cone. When you push the shifter toward second gear, you’re actually pushing this brass cone against the side of the gear. Friction causes the gear to speed up or slow down until it’s spinning at the exact same RPM as the output shaft. Only then do the "dog teeth" lock into place. It’s a mechanical negotiation.

The Role of the Shift Fork

The shift fork is the physical extension of your arm. When you move that stick in the center console, you’re sliding a rail. That rail moves a fork. That fork grabs a collar (the slider).

- You move the stick.

- The fork pushes the slider.

- The slider hits the synchro.

- The synchro matches speeds.

- The slider locks onto the gear.

It happens in a heartbeat. But if your synchros are worn out, that negotiation fails. That’s why your old Honda might "crunch" when you try to shift into third too fast on a cold morning. The brass is tired. It can’t grab the gear hard enough to synchronize the speeds before the teeth try to meet.

Power Flow: Following the Torque

Let’s trace a path. You’re in first gear. Power comes off the flywheel, through the clutch disc, and into the input shaft. The input shaft turns the countershaft. Because the first gear on the countershaft is small and the first gear on the output shaft is huge, you get massive torque. This is "gear reduction." You need it to move two tons of steel from a dead stop.

As you move up to fifth or sixth gear, the ratio flips. Now, the gear on the countershaft is almost the same size (or larger) than the one on the output shaft. This is "overdrive." The engine can relax at 2,000 RPM while the wheels are screaming at highway speeds.

Without a clear diagram of manual transmission ratios, it’s hard to see how much work that countershaft is doing. It’s the backbone of the entire unit. If the bearings on that shaft go bad, you’ll hear a low-pitched whirring sound in every gear except fourth (usually, because fourth is often a 1:1 direct drive where the input and output shafts are basically locked together).

The Reverse Gear Oddity

Have you ever noticed that reverse sounds... different? It whines. It sounds like a remote-controlled car.

There’s a reason for that.

Forward gears use "helical" teeth. They are cut at an angle. This allows the teeth to engage gradually, which makes them quiet and strong. But reverse usually uses "spur" gears—straight-cut teeth. When straight teeth hit each other, they trap air and oil between them, creating that signature "whirrr" sound. Also, a diagram of manual transmission reverse sets will show a third "idler" gear. To make the car go backward, you have to insert a third gear between the countershaft and the output shaft to flip the direction of rotation.

It’s the only time gears actually "slide" into mesh in a modern car, which is why you sometimes have to wiggle the shifter to get it into reverse. The teeth are literally hitting each other head-on.

Maintenance Reality Check

We need to talk about "Lifetime Fluid." Many manufacturers claim the oil inside your manual gearbox never needs to be changed. Honestly? That’s nonsense.

While a manual transmission is vastly more durable than an automatic or a CVT, it still generates heat. It still has metal-on-metal wear. Those brass synchronizers we talked about? They wear down over time, leaving microscopic gold-colored flakes in the oil.

📖 Related: Latest Mac Software Update: Why the macOS Tahoe 26.3 Beta Is Polarizing Users

If you want your transmission to last 300,000 miles, change the gear oil every 50,000 to 60,000 miles. Use exactly what the manual calls for. Some gearboxes need thin ATF; others need thick 75W-90 GL-4. If you put GL-5 (which has sulfur additives) into a transmission designed for GL-4, you can actually chemically corrode your brass synchros. It’s a slow death for your gearbox.

The Future of the Manual

The manual transmission is a dying breed, mostly because computers can shift faster than humans can blink. A dual-clutch transmission (DCT) is technically an automated manual, using two separate shafts and two clutches to "pre-select" the next gear. It’s faster. It’s more efficient.

But it’s not as visceral.

There is a psychological connection when you perfectly rev-match a downshift into a tight corner. You feel the mechanical gate. You hear the engine sing. A diagram of manual transmission mechanics shows a system that requires a human in the loop to function correctly. That’s why enthusiasts still hunt for them.

Diagnosing Problems by Sound

- Whining in all gears: Likely the input shaft or countershaft bearings.

- Grinding only during the shift: Worn synchronizer rings.

- Popping out of gear: Worn shift forks or rounded "dog teeth" on the gears themselves.

- Vibration through the shifter: Could be a failing transmission mount or a badly balanced driveshaft.

Practical Next Steps for the DIYer

If you’re looking at a diagram of manual transmission parts because your car is acting up, don't panic. Start with the basics.

First, check your clutch hydraulics. A lot of "transmission" problems are actually just a leaking slave cylinder that isn't fully disengaging the clutch. If the clutch doesn't fully let go, the synchros can't do their job, and you'll get grinding.

Second, check your shift bushings. If your shifter feels like a "spoon in a bowl of oatmeal," it’s probably just the cheap plastic bushings at the base of the lever. Replacing those costs $20 and can make an old car feel brand new.

Finally, if you do decide to crack the case open, keep everything sterile. A single grain of sand in a needle bearing can end a transmission's life in a few hundred miles. Lay everything out on a clean bench in the exact order it came off the shaft. Take photos of every step. Even a pro can get confused when looking at fifteen different gears that all look slightly similar.

Understanding the mechanics doesn't just make you a better mechanic; it makes you a better driver. You start to "feel" what the synchros need. You stop rushing the shifts. You become part of the machine.

Next Steps:

If you suspect internal damage, your first move should be to drain the gear oil into a clean pan. Inspect the oil for "glitter." Small amounts of fine dust are normal, but chunks of steel or heavy gold flakes mean it's time for a rebuild or a replacement unit. If the oil is clean, look toward your clutch master and slave cylinders as the likely culprits for shifting issues.