You probably remember sitting in a stuffy middle school classroom when a teacher first scrawled a rectangular prism on the chalkboard. "Length times width times height," they said. It felt simple. Maybe even a little boring. But honestly, the volume in physics formula is one of those fundamental concepts that starts easy and then gets incredibly weird once you move into the real world of fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and even quantum mechanics.

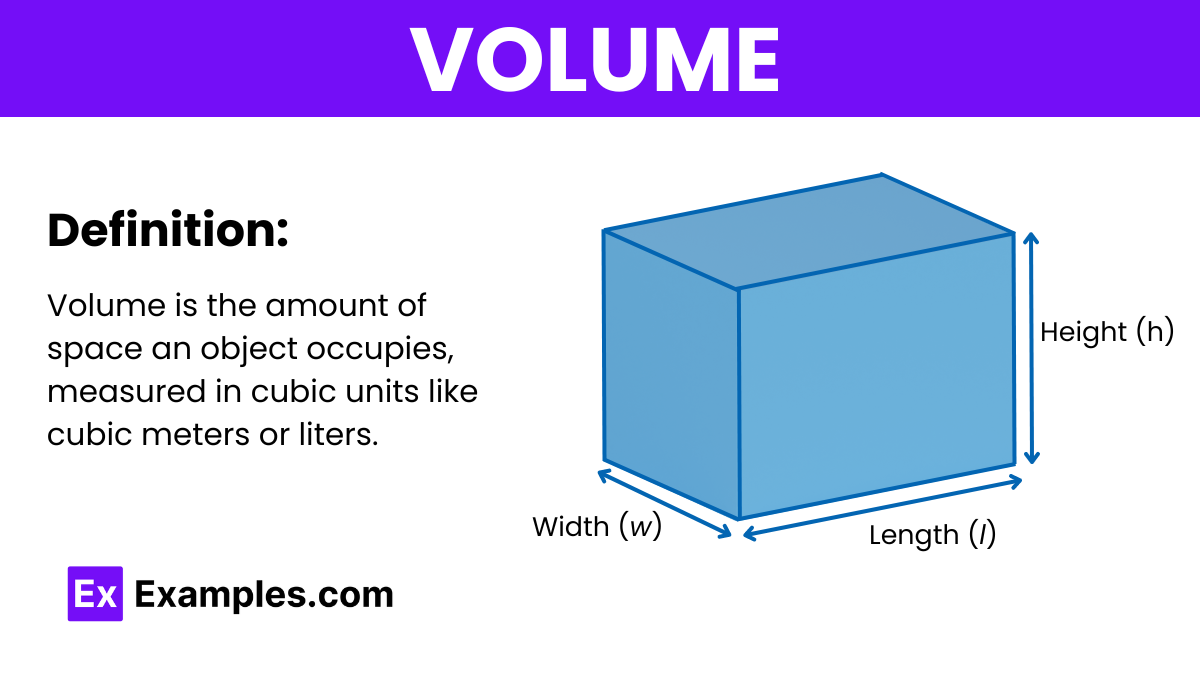

Volume is just space. That’s the easiest way to think about it. It is the three-dimensional "bucket" that an object occupies. If you have a solid gold bar, the volume is how much room that gold takes up in your safe. If you have a lungful of air, it’s the capacity of your chest cavity. In the International System of Units (SI), we measure this in cubic meters ($m^3$), though in a lab, you're much more likely to see milliliters or cubic centimeters.

The Basics Everyone Forgets

We usually start with the "nice" shapes. You’ve got your cubes where $V = s^3$. You’ve got your spheres where $V = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3$. These are the "spherical cows" of the physics world—idealized versions of reality that make the math clean. But nature rarely hands you a perfect sphere.

If you are dealing with a gas, volume isn't even a fixed property of the object itself. It’s a property of the container. This is where the volume in physics formula shifts from geometry into the territory of the Ideal Gas Law:

$$PV = nRT$$

In this context, $V$ (volume) is inextricably linked to $P$ (pressure) and $T$ (temperature). If you squeeze a balloon, the volume decreases because the pressure increases. If you heat that same balloon, the volume expands. This isn't just a math trick; it's why car tires look flat on a freezing January morning and why aerosol cans have "do not incinerate" warnings. If the volume is fixed by a metal can and you crank the temperature, the pressure has nowhere to go but out through the seams.

Archimedes and the "Aha!" Moment

You can't talk about volume without mentioning the bathtub incident. We’ve all heard the story of Archimedes running through the streets of Syracuse naked, shouting "Eureka!" because he realized he could measure the volume of an irregular crown by seeing how much water it displaced.

It’s a classic for a reason. For any solid object that doesn't dissolve, its volume is exactly equal to the volume of the fluid it displaces.

💡 You might also like: Minnesota DOT Traffic Cameras: What Most People Get Wrong

Suppose you have a jagged piece of jagged quartz. There is no simple geometric formula for that. You aren't going to sit there with a ruler measuring a thousand tiny facets. You drop it in a graduated cylinder, note the rise in the water level, and boom—you have the volume. This displacement method is still the gold standard in laboratory density checks.

When Volume Gets Complicated: The Density Link

Physics isn't interested in volume just for the sake of measuring space. It’s usually a stepping stone to finding mass or density. The formula $\rho = \frac{m}{V}$ (where $\rho$ is density) is the bridge.

Think about a pound of lead versus a pound of feathers. The mass is the same. The weight is the same. But the volume in physics formula tells us they occupy vastly different amounts of space because their densities are worlds apart. Lead is dense; its atoms are packed tight, so its volume is tiny. Feathers are mostly air and fluff, requiring a massive volume to reach that same one-pound mark.

In astrophysics, this gets extreme. A neutron star might have the mass of our Sun but the volume of a small city. We are talking about taking something as big as a star and crushing it down until the volume is so small that a single teaspoon of it would weigh billions of tons. Here, the volume isn't just a measurement; it’s a testament to the staggering power of gravity overcoming atomic repulsion.

Specific Volume and Thermodynamics

If you work in engineering or HVAC, you’ll run into "specific volume." This is basically the upside-down version of density. Instead of asking how much mass is in a certain space, you ask how much space one kilogram of a substance occupies.

$v = \frac{V}{m}$

Why does this matter? Because when you’re designing a steam turbine, you need to know exactly how much that water is going to expand when it turns into vapor. Water as a liquid has a very small specific volume. As steam? It expands by a factor of about 1,600 at atmospheric pressure. If you don't account for that change in the volume in physics formula, your pipes are going to explode.

The Trouble with Liquids and Solids

We often treat liquids as "incompressible." For most high school physics problems, we assume that no matter how hard you push on a liter of water, it stays a liter.

That’s technically a lie.

👉 See also: How Do You Remove an App From iPad: What Most People Get Wrong

If you go deep enough into the ocean—say, the Mariana Trench—the sheer weight of the water above actually compresses the water at the bottom. Its volume shrinks by about 4 to 5 percent. In high-precision physics, we use the Bulk Modulus to calculate this. It describes how much a substance's volume changes under pressure. For solids, this change is minuscule, but in the world of tectonic plates and planetary cores, those tiny shifts in volume drive the heat and pressure that move continents.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

One of the biggest mistakes students make is confusing capacity with volume. While they are related, they aren't synonyms in a strict physics sense. Volume is the space an object takes up. Capacity is the amount a container can hold. A thick-walled glass bottle might have a large exterior volume but a very small internal capacity.

Another trap? Units. Always units. If you calculate the length in centimeters, the width in millimeters, and the height in meters, your final "volume" is going to be a nonsensical mess. In the volume in physics formula, consistency is everything.

- Check your dimensions: Always ensure all measurements are in the same unit before multiplying.

- Account for Temperature: If you’re measuring the volume of a gas or a precision metal part, note the temperature. Metals expand when hot (thermal expansion), which changes their volume.

- Significant Figures: Don't claim a volume is $10.52345$ cubic centimeters if your ruler only measures to the nearest millimeter. Your result is only as good as your worst measurement.

Practical Next Steps

If you're trying to master volume for a class or a project, don't just memorize formulas. Start by visualizing the "unit cube." Imagine a small box that is 1cm on all sides. How many of those boxes would fit inside the object you're looking at?

- For irregular objects: Use the displacement method. Fill a measuring cup, drop the item in, and subtract the original level from the new level.

- For gases: Remember the balloon. If you double the pressure, you'll halve the volume (Boyle’s Law).

- For engineering: Look up the "Coefficient of Thermal Expansion" if you're dealing with materials that will be exposed to extreme heat or cold.

Volume is the stage upon which all other physics happens. Whether you are calculating the displacement of a cargo ship or the expansion of the universe itself, the math stays rooted in those three dimensions of space. Stop seeing it as a static number and start seeing it as a dynamic property that reacts to the world around it.