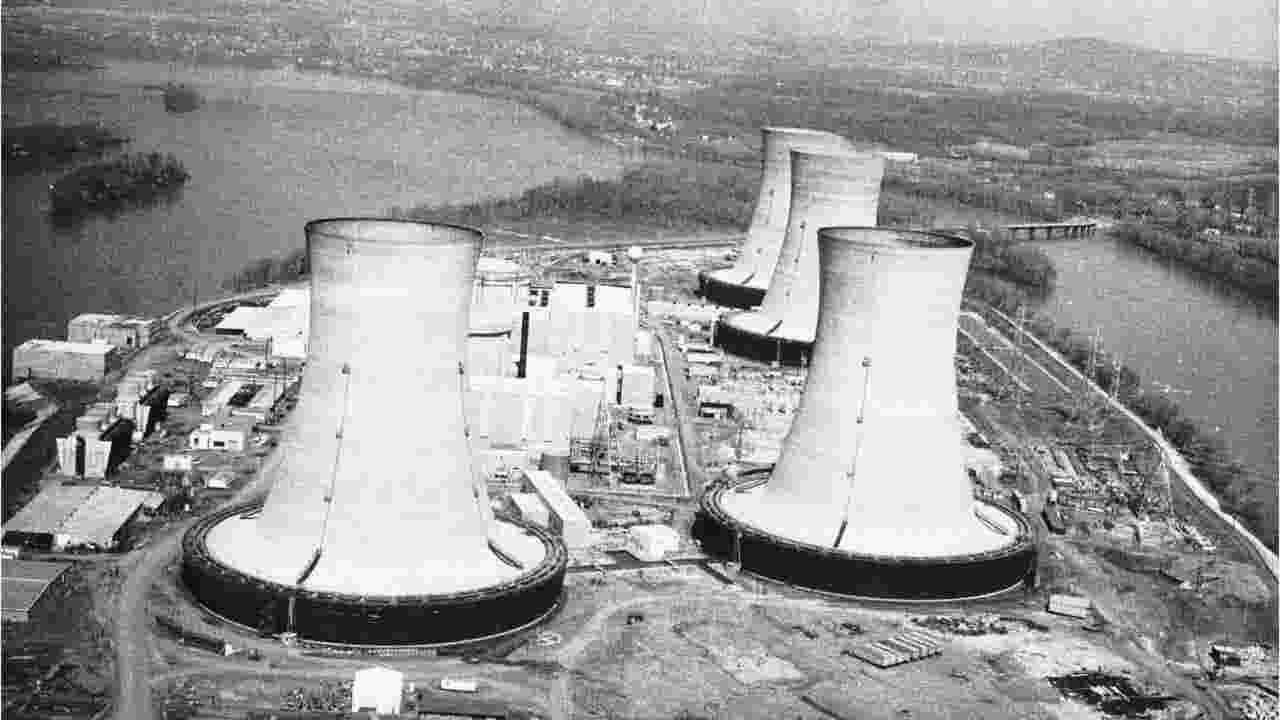

March 28, 1979. It started at 4:00 AM. Most people in Middletown, Pennsylvania, were fast asleep, totally unaware that a cooling pump had just failed in Unit 2 of the Three Mile Island nuclear generating station. It was a mechanical hiccup. Small. Fixable. But then, things got weird. A series of human errors, stuck valves, and confusing instrument readings turned a routine malfunction into the worst accident in the history of U.S. commercial nuclear power.

You've probably heard the term "meltdown" tossed around in movies. People think of glowing green ooze or massive explosions. Reality is a lot more boring, and somehow, a lot scarier. At Three Mile Island, the core didn't explode. It just got really, really hot because the water meant to cool it was leaking out of a valve that everyone thought was closed.

The 120-Minute Chain Reaction

The mechanical failure was actually pretty simple. A pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) opened to relieve pressure but failed to shut. This is where it gets messy. The control room lights indicated that the command to close the valve had been sent, so the operators assumed it was closed. It wasn't.

For over two hours, precious coolant poured out of the system. Imagine trying to drive a car while the oil is draining out, but your dashboard tells you the tank is full. That’s basically what the operators were dealing with. They actually turned off the emergency cooling water because they thought the system was "solid"—meaning too full of water. In reality, the top of the reactor core was uncovered and starting to cook.

By the time they figured out what was happening, the damage was done. About half the core had melted.

Why the "Hydrogen Bubble" Scared Everyone

A few days after the initial crisis, a new fear took over: the bubble. Experts at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) worried that a large bubble of hydrogen gas inside the containment building might explode.

This was the peak of the panic. Governor Dick Thornburgh advised pregnant women and preschool-aged children within five miles of the plant to evacuate. This wasn't a forced order, but it sent a clear message: we aren't sure if you're safe. Roughly 140,000 people packed their bags and left.

The kicker? The bubble couldn't actually explode. There wasn't enough oxygen present in the system for combustion. It took days for the scientists to realize the math didn't support a blast, but by then, the public's trust was already in the trash. You can't really blame them. When the "experts" are arguing on live TV about whether a town is going to disappear, you're going to start the car and drive.

What Three Mile Island Did to the Industry

Before 1979, nuclear power was on a roll. It was the "too cheap to meter" dream. After 1979? Everything stopped.

The industry didn't just slow down; it hit a brick wall. No new nuclear power plants were authorized for construction in the United States for decades. The plants that were already being built faced massive new regulations that sent costs through the roof. Honestly, the economic fallout was almost as significant as the technical failure.

We saw the birth of the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO). The industry realized that if one plant messed up, they all looked bad. They started policing each other. They standardized training. They fixed the interfaces in control rooms so that a "closed" light actually meant the valve was closed, not just that someone had pushed a button.

The Health Debate: Did It Actually Hurt People?

This is where things get controversial. If you look at the official reports from the NRC, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Department of Health and Human Services, they all say the same thing: the radiation release was negligible.

The average dose to people living within ten miles was about 8 millirem. To put that in perspective, a single chest X-ray is about 6 millirem. You get more radiation from the sun during a cross-country flight than most people got from Three Mile Island.

But—and it’s a big "but"—local activists and some residents tell a different story. Organizations like the TMI Alert point to anecdotal clusters of cancer and hypothyroidism in the area.

💡 You might also like: 2026 Toyota Hilux Interior: Why It Is Finally Leaving the 1990s Behind

There were dozens of lawsuits. In the end, the courts generally ruled that there wasn't enough evidence to link the accident to local health issues. But the psychological trauma? That was real. You can’t measure the stress of 140,000 people thinking they were about to be "Chernobyled" seven years before Chernobyl even happened.

The China Syndrome Factor

Timing is everything.

Twelve days before the accident, a movie called The China Syndrome hit theaters. It starred Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas, and the plot was eerily similar to what happened in Pennsylvania. It even featured a line about how an accident could render an area "the size of Pennsylvania" uninhabitable.

You couldn't script a worse PR disaster for the nuclear industry. The public went into the theater to see a thriller and walked out to see the same thing happening on the nightly news. It blurred the lines between Hollywood fiction and engineering reality. People weren't just reacting to a valve failure; they were reacting to a cultural moment.

Cleaning Up the Mess

Cleaning up Unit 2 wasn't like mopping a floor. It took 14 years and cost about $1 billion.

👉 See also: Red White and Blonde Hat: The Ethics of Cybersecurity Explained

Workers had to use remote-controlled cameras and robotic tools to see inside the reactor because the radiation levels were too high for humans. They eventually shipped the damaged fuel to a Department of Energy facility in Idaho. Unit 1, the sister reactor that wasn't involved in the accident, actually kept running until 2019. It’s kinda wild to think that people were going to work every day right next to the site of the most famous nuclear accident in America.

Lessons for the Future of Energy

So, what do we actually do with this information? Nuclear energy is back in the conversation because of climate change. Tech giants like Microsoft are even looking at restarting Three Mile Island’s Unit 1 to power AI data centers.

If we're going to move forward, we have to look at the TMI legacy through a clear lens:

- Human factors matter more than hardware. The hardware failed, but the humans made it an "accident" by not understanding what the hardware was telling them. Modern reactor designs (like SMRs) focus on "passive safety" where physics—not a human with a switch—shuts the reactor down.

- Transparency is the only way to keep trust. The NRC’s confusing communication in 1979 did more damage than the radiation. In the age of social media, any future incident requires instant, brutal honesty.

- Regulations are a double-edged sword. The safety changes post-TMI made nuclear the safest form of energy per terawatt-hour produced, but they also made it incredibly expensive to build.

To really understand the impact, look at the cooling towers next time you're in the area. They aren't just concrete structures. They are monuments to a moment when we realized that our technology had outpaced our ability to manage it.

If you're interested in the technical side of energy or the history of industrial safety, your next step should be to look into the "Passive Safety" features of Generation IV reactors. Understanding how new tech prevents a repeat of 1979 is the best way to evaluate whether nuclear deserves a second chance in our power grid. Reading the 1979 Kemeny Commission Report is also a great move if you want to see exactly how the government dissected the failure. It’s a masterclass in forensic engineering.