You’ve probably heard the name Eli Whitney since third grade. It’s one of those history facts that sticks, right up there with the 1776 or the lightbulb. But if you're asking when was the cotton gin invented, the answer isn't just a single date on a calendar. It's a messy story of 1793, 1794, and a whole lot of legal drama that basically ruined the inventor's life while simultaneously changing the entire world.

Most history books point to 1793 as the big year. That’s when Whitney, a Yale graduate who was actually just looking for a job as a tutor, built a prototype in Georgia. He was staying at Mulberry Grove, the plantation of Catherine Littlefield Greene. Honestly, he was just a tinkerer. He saw how slow it was to pull seeds out of short-staple cotton by hand—literally a whole day's work for just one pound of lint—and thought he could do better. He did. By 1794, he had a patent.

But here's the thing: it wasn't just a "eureka" moment in a vacuum.

👉 See also: iPad Pro 11 inch 4th generation case: What Most People Get Wrong About Protection

The 1793 Breakthrough and the Patent Struggle

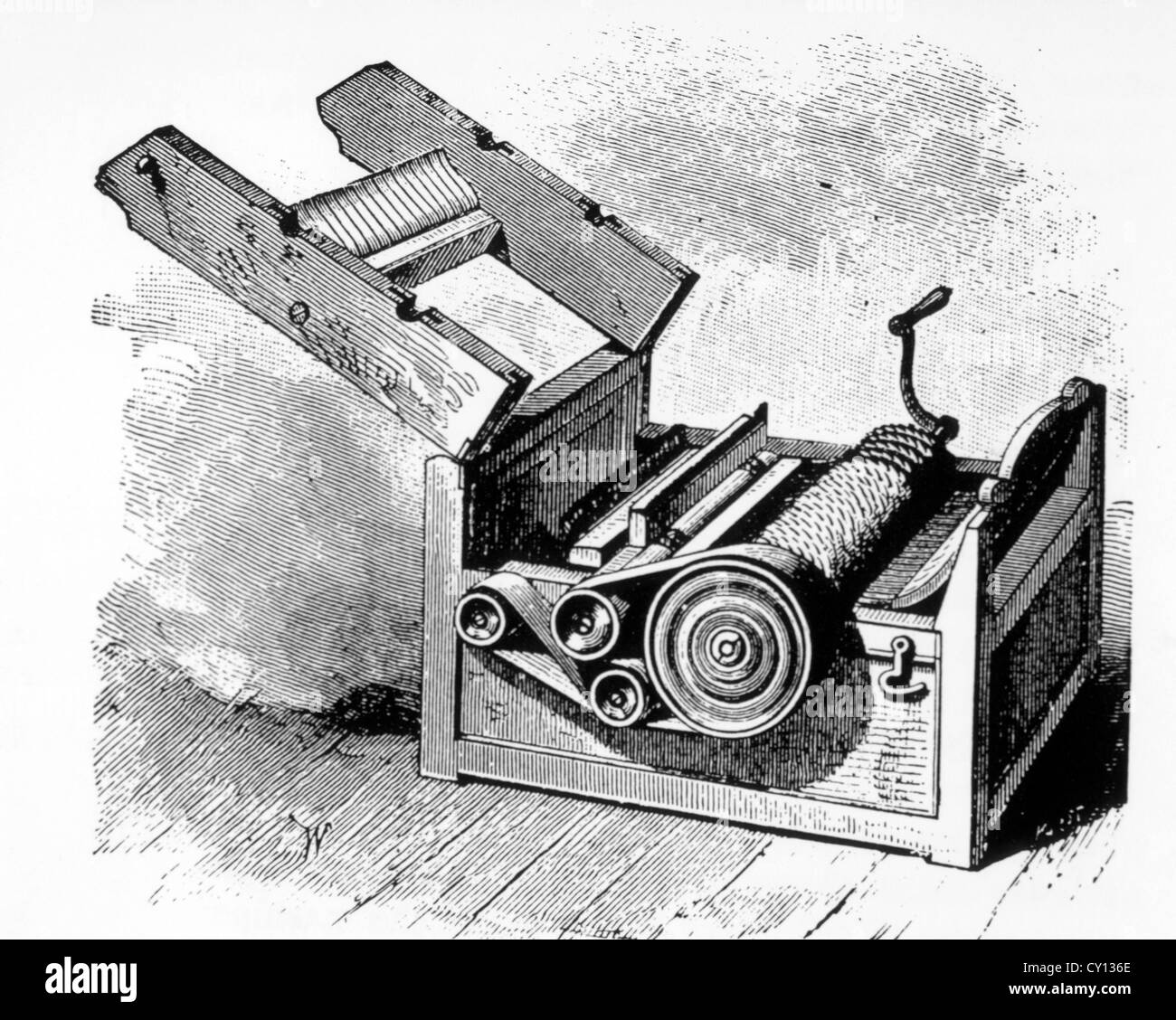

The timeline of when was the cotton gin invented usually starts with Whitney’s arrival in the South in late 1792. By early 1793, he had the machine running. It was simple. It used a wooden drum with hooks that pulled cotton fibers through a mesh. The seeds, being too big for the mesh, just dropped away. It was genius. It was also incredibly easy to copy.

Because the design was so straightforward, every blacksmith in the South started making their own version before Whitney could even get his patent paperwork finalized in March 1794. He and his partner, Phineas Miller, tried to charge farmers a massive fee—two-fifths of the profit—to use the machines. Farmers hated that. They just built their own and told Whitney to sue them. He did. He spent years in court.

History is rarely about one guy in a room. While Whitney gets the credit, there’s a lot of talk among historians about how much Catherine Greene contributed. Some say she suggested the use of brush bristles to clear the lint off the hooks, which was the one part of the machine that kept jamming. Without those brushes, the cotton gin was basically a box of tangled string.

Why the Date 1793 Matters More Than You Think

It changed everything. Before when the cotton gin was invented, slavery was actually starting to decline in the United States. Tobacco was wearing out the soil. Rice and indigo weren't profitable enough. Many people thought slavery might just fade away because it wasn't making enough money.

The gin changed that math overnight.

👉 See also: Why Emoticon Faces Copy and Paste Still Rules the Internet

Suddenly, short-staple cotton, which grows almost anywhere in the South, became a gold mine. Production exploded. In 1790, the U.S. produced about 1.5 million pounds of cotton. By 1800? It was 35 million pounds. By 1860? Two billion.

It's a dark irony. A labor-saving device actually made the demand for forced labor skyrocket. The "Cotton Kingdom" was born because of a small wooden box built in 1793. It moved the center of American slavery from the Chesapeake to the Deep South, tearing families apart in the process.

The Tech Before the Tech: Was Whitney Really First?

If we're being pedantic about when was the cotton gin invented, we have to look back centuries. The "churka" gin had existed in India for a long, long time. It used rollers to squeeze out seeds. But the churka only worked on long-staple cotton, which only grows near the coast.

Whitney’s "invention" was specifically for the sticky-seeded upland cotton.

There were also others claiming they had the idea first. A guy named Hodgen Holmes actually improved Whitney’s design by using saw blades instead of wire hooks. This made the machine way more efficient. Whitney sued him, too. It wasn't until 1807 that Whitney finally won his legal battles, but by then, he was mostly over it. He eventually gave up on cotton and went into the arms industry, where he pioneered interchangeable parts for muskets.

The Economic Aftershocks

Think about the global scale. Great Britain’s Industrial Revolution was basically fueled by the cotton coming out of the American South. The textile mills in Manchester needed raw material. Whitney’s machine provided it.

- 1793: Prototype built.

- 1794: U.S. Patent granted.

- 1803: The states of North and South Carolina eventually paid Whitney some royalties, though it was a fraction of what he thought he was owed.

- The 1850s: Cotton accounts for over half of all U.S. exports.

It’s wild how one piece of tech can pivot the entire trajectory of a superpower. Without the gin, the American Civil War might never have happened the way it did. The economic divide between the industrial North and the cotton-dependent South became an unbridgeable chasm.

Common Misconceptions About the Invention

People often think Whitney got rich from the gin. He didn't. He barely broke even after paying his lawyers. He also didn't "invent" the concept of ginning cotton—the word "gin" is just short for "engine." He just mechanized a specific, grueling part of the process for a specific type of plant.

Another weird detail? The patent office at the time was tiny. Thomas Jefferson was actually the one who reviewed Whitney's application. Jefferson, being a farmer himself, was fascinated by it. He asked Whitney if it could be made smaller so individual families could use it. Whitney, wanting to maintain a monopoly, wasn't interested in that.

👉 See also: The Google Vertex AI Logo: Why That Geometric Infinity Loop Actually Matters

Actionable Insights and Tracking the Legacy

If you're researching this for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, don't just stop at the date. Understanding the "when" requires looking at the "why."

- Check the Patent Records: Look for the 1794 patent documents online via the National Archives. They show the original drawings, which are surprisingly simple.

- Visit the Sites: If you're ever in Georgia, the Eli Whitney Museum in Connecticut is actually where most of his later work is, but the Mulberry Grove site near Savannah is where the real history happened.

- Read Beyond Whitney: Look into the "Great Divergence" theory. It explains how the cotton gin helped the West pull ahead of the East economically during the 19th century.

- Analyze the Impact: When writing or teaching about this, always link the technology to the human cost. You can't separate the machine from the expansion of slavery.

The invention of the cotton gin wasn't a clean, happy moment of progress. It was a 1793 spark that started a fire. It made the South wealthy, it made slavery a permanent fixture for another 70 years, and it ultimately set the stage for the bloodiest war in American history. It’s a classic example of how technology always has unintended consequences.

To truly grasp the timeline, you have to see 1793 as the year the American economy shifted its weight. It wasn't just a new tool; it was the birth of a new, and deeply flawed, era.