History is messy. If you ask a random person on the street about when guns were invented, they might mention the American Wild West or maybe some guy in a powdered wig during the Revolutionary War. They'd be off by roughly five hundred years.

Honestly, the "invention" of the gun wasn't a single "Eureka!" moment in a lab. It was a slow, sometimes accidental transition from Chinese alchemy to terrifying battlefield reality. It started with a search for eternal life. Irony is funny like that. Around the 9th century, Taoist monks in China were messing around with saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sulfur, and charcoal. They weren't trying to blow things up; they were trying to find an elixir of immortality. Instead, they created "fire medicine"—gunpowder.

The first "gun" wasn't even a gun in the way we think of them. It was a fire lance. Basically, a bamboo tube tied to a spear. You’d pack it with gunpowder and bits of scrap metal or stones, light it, and hope it didn't explode in your hands while you pointed the flame-spewing end at your enemy. It was more of a psychological weapon than a precision tool. Imagine the terror of seeing a tube screaming fire and smoke toward you in a world where the loudest thing most people had ever heard was a thunderstorm.

The 13th Century Shift: From Bamboo to Bronze

By the late 1200s, things got serious. Bamboo is great for a one-off blast, but it doesn't hold up to repeated pressure. You need metal for that. This is the era where we see the first true "hand cannons."

The Heilongjiang hand cannon, discovered in Manchuria, is one of the oldest surviving examples we have, dating back to roughly 1288. It's a chunky, bronze tube. No trigger. No stock. No sights. You held it in one hand (or braced it against the ground) and touched a burning coal or a slow-burning fuse to a touchhole. It was crude. It was heavy. But it changed everything.

Why the Middle East and Europe caught on so fast

Knowledge traveled. The Silk Road wasn't just for spices and silk; it was an information superhighway for military tech. By the mid-1300s, gunpowder recipes and the basic design of the "fire tube" had reached the Islamic world and Europe.

Western smiths were already experts at casting large bells for churches. They realized that if you could cast a bell to ring, you could cast a tube to shoot. This led to the development of the "bombard"—massive, early cannons used to smash down castle walls. These things were beasts. They were so heavy they’d often sink into the mud, and they had a habit of exploding and killing their own crews. James II of Scotland actually died when one of his own cannons burst during a siege in 1460.

The Matchlock: The Moment Guns Became Practical

For a long time, guns were basically "portable artillery." You couldn't aim them well because you needed one hand to hold the gun and the other to hold the match. Then came the matchlock in the mid-1400s.

The matchlock was the first mechanical "action." It used a S-shaped lever called a serpentine. When you pulled a trigger, it dropped a piece of burning cord (the "slow match") into a pan of priming powder. For the first time, a soldier could keep both hands on the weapon and actually look down the barrel to aim. This is when guns were invented in a form that any modern person would actually recognize as a firearm.

But let's be real—the matchlock sucked in the rain. If your match went out, you were left holding a very expensive club. It also glowed in the dark, which is pretty much the last thing you want if you’re trying to be sneaky on a night patrol.

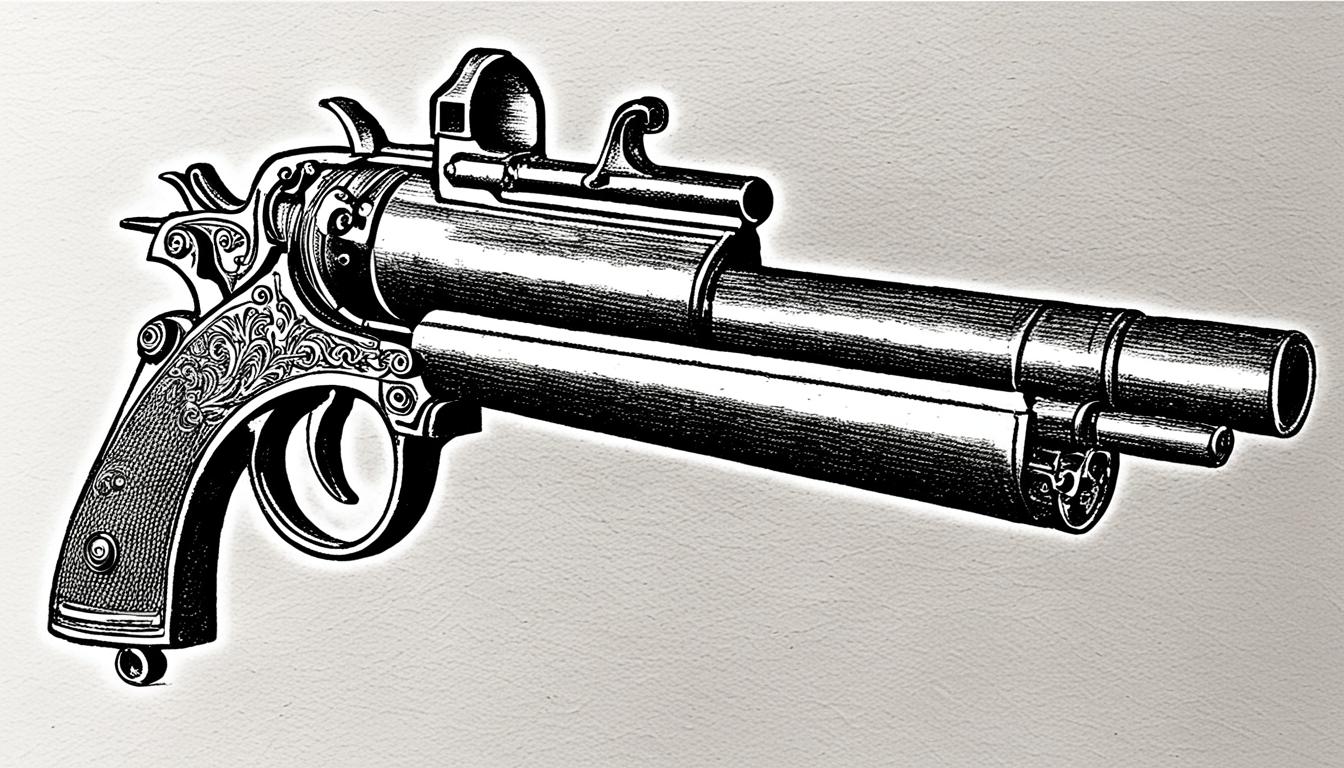

The Wheel Lock and the Birth of the "Cool" Gun

Because matchlocks were so finicky, the 16th century gave us the wheel lock. Think of it like a giant Zippo lighter. A serrated steel wheel spun against a piece of pyrite to create sparks.

- It was incredibly complex.

- It was insanely expensive.

- It allowed for the first truly concealable pistols.

Only the wealthy could afford them. Aristocrats used them for hunting and self-defense. Leonardo da Vinci even sketched out designs for wheel lock mechanisms in his notebooks. Because they didn't require a burning fuse, you could carry a loaded wheel lock in your pocket or holster indefinitely. This was the birth of the "sidearm" culture.

The Flintlock Era: 200 Years of Dominance

Around 1610, a Frenchman named Marin le Bourgeoys created what we now call the "true" flintlock. It was simpler than the wheel lock and way more reliable than the matchlock. You had a piece of flint held in a cock (the hammer). When you pulled the trigger, the flint struck a steel plate called a frizzen. Sparks dropped into the pan. Boom.

This technology was so effective that it barely changed for two centuries. It’s what the British Redcoats used. It’s what the Continental Army used. It’s what pirates used. When people think about the history of firearms, this is usually the image that pops into their heads.

The Industrial Revolution and the Death of the Muzzle-Loader

Everything changed in the 1800s. It was a chaotic century for gun tech. First, we got the percussion cap. Instead of flint and sparks, you had a tiny copper cap filled with fulminate of mercury. You hit it, it exploded, and ignited the main charge. No more "flash in the pan." It worked in the rain. It was faster.

Then came the "minie ball." It wasn't actually a ball; it was a conical bullet with a hollow base. When fired, the base expanded to grip the rifling (the grooves inside the barrel). Suddenly, a soldier who could previously hit a target at 50 yards could now hit one at 300 yards. The carnage of the American Civil War was largely due to this leap in tech—old-school tactics meeting modern-day lethality.

The Breakthrough of Breech-Loading

For hundreds of years, you had to pour powder down the front of the gun and ram a ball on top. It was slow. If you were lying down, it was almost impossible.

The introduction of the "needle gun" and later the metallic cartridge changed the game. Putting the powder, the primer, and the bullet into one single brass case was the real revolution. By the 1860s and 70s, breech-loaders like the Sharps rifle and the Winchester repeater allowed people to fire multiple shots in seconds.

Modern Misconceptions and the "First" Gun

We often want to point to one person and say, "They invented the gun." It doesn't work like that. Was it the monk who found the powder? Was it the Chinese smith who cast the first bronze tube? Was it the European clockmaker who built the first trigger?

The truth is, "when guns were invented" is a timeline, not a date.

- 900s: Gunpowder discovery in China.

- 1100s: Fire lances (bamboo tubes).

- 1280s: Metal hand cannons emerge.

- 1411: First recorded mention of a matchlock.

- 1835: Samuel Colt patents the first practical revolver.

- 1880s: Smokeless powder makes modern high-velocity rounds possible.

The jump from the 1200s to the 1800s is where the most radical changes happened. We went from "shoving a burning coal into a hole" to "semi-automatic fire" in a relatively short span of human history.

Evidence in the Dirt: What Archaeology Tells Us

We know these dates because of physical evidence, not just old stories. The Xanadu Gun, found in Inner Mongolia, dates to 1298. It has a roomier "powder chamber" and a narrower muzzle, showing that even then, people understood the physics of internal ballistics. They knew that compressing the explosion made the projectile go faster.

In Europe, the "Losshult Gun" found in Sweden is another touchstone. It looks like a small vase. It’s heavy, bronze, and was likely used to shoot bolts (like crossbow bolts) rather than round lead balls.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're looking to dig deeper into the actual evolution of firearms without getting bogged down in "tacticool" modern nonsense, here is how you should approach it:

Look at the Metallurgy

Don't just look at the wood and the triggers. The real story of the gun is the story of steel. Until we could create high-quality, consistent steel that wouldn't shatter under pressure, guns were dangerous to the user. Researching the Bessemer process will tell you more about 19th-century rifles than reading any gun manual.

Visit the Right Museums

The "Royal Armouries" in Leeds, UK, or the "Smithsonian" in D.C. have the actual physical specimens. Seeing a 14th-century hand cannon in person changes your perspective. It’s much smaller—and much heavier—than you think.

Primary Source Reading

Check out the Wujing Zongyao (Complete Essentials for the Military Classics) from 1044. It contains some of the earliest recorded formulas for gunpowder. It's fascinating to see how they balanced the ingredients before they even knew what "chemistry" really was.

Understand the "Why"

Guns didn't immediately replace bows. Longbows were faster and more accurate for a long time. Guns took over because you could train a peasant to use a matchlock in a week, whereas a longbowman took a lifetime to train. The invention of the gun was as much about "mass production" of soldiers as it was about the technology itself.

The story of the gun is ultimately a story of human ingenuity and our relentless drive to reach further, hit harder, and master the physical world—for better or worse. Knowing when guns were invented helps us understand the pivot point where medieval warfare died and the modern world began.

🔗 Read more: Digital Finance Research Institute: What's Actually Happening Behind the Scenes

The transition from a bamboo tube to a digital smart-optic rifle is a long one, but the basic principle remains exactly the same as it was in a 13th-century Chinese workshop: controlled explosion, directed energy. All the rest is just refinement.