Martin Cooper stood on a busy New York City sidewalk in 1973 and did something that looked absolutely insane to every passerby. He pulled out a beige plastic brick the size of a toaster and started talking to it.

He wasn't crazy. He was making history.

People ask who invented the first mobile cell phone like it was a single "eureka" moment in a basement somewhere. Honestly? It was more like a high-stakes corporate street fight. While we give the trophy to Cooper and the team at Motorola, the story is actually about a decades-long rivalry with AT&T that almost strangled the technology before it even breathed.

The Day the World Changed (and Nobody Noticed)

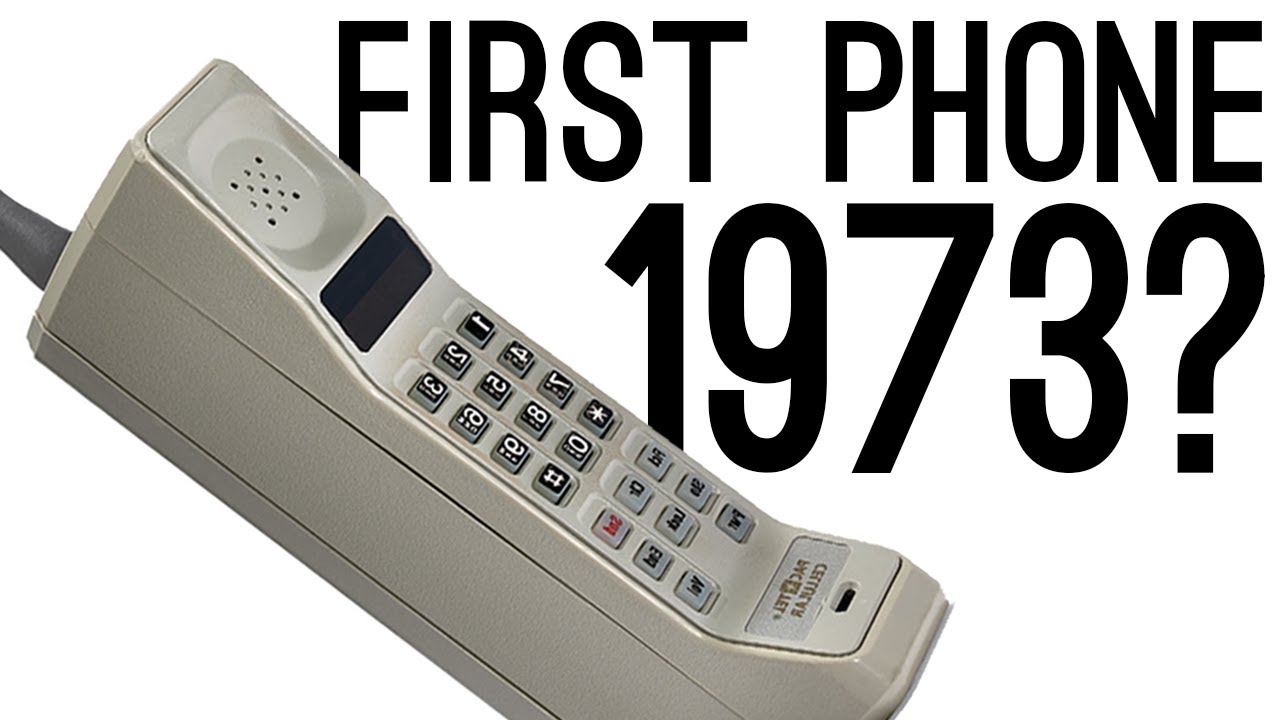

It was April 3, 1973. Cooper, a senior engineer at Motorola, was standing outside the New York Hilton. He had this device in his hand—the DynaTAC 8000X. It weighed two and a half pounds. It was ten inches long. You could literally use it as a blunt force weapon if you had to.

👉 See also: What Tool is Used to Measure Capacity? The Short Answer and the Complicated Reality

But he didn't call his wife. He didn't call his boss.

He called Joel Engel.

Engel was his chief rival at Bell Labs (AT&T). Imagine the level of petty brilliance required for that. Cooper dialed the number, waited for Engel to pick up, and basically said, "Joel, I’m calling you from a real, handheld, portable cell phone."

Silence.

Engel doesn't remember the call quite the same way—or claims not to—but that moment marked the official birth of the cellular age. Motorola, the scrappy underdog at the time, had beaten the world's largest monopoly at their own game.

It Wasn't Just One Guy

We love a lone genius narrative. It's clean. It's easy for history books. But Cooper would be the first to tell you he didn't build the thing with a screwdriver in his garage.

The real credit for who invented the first mobile cell phone belongs to a massive engineering team. John F. Mitchell, Motorola’s chief of portable communication products, was the driving force who pushed for the "personal" aspect of phones. Mitchell was the one who envisioned a world where people didn't call a place (a house or a desk), but a person.

Then you had guys like Rudy Krolopp, the lead designer. His job was to make a massive radio transmitter small enough for a human to grip. They only had 90 days to build the prototype. They actually held a contest among the designers at Motorola, and Krolopp’s team won with a design that looked remarkably like the "brick" we all remember from 80s movies.

Why AT&T Almost Won

You have to understand the context of the 1970s. AT&T wasn't trying to make a handheld phone. They were obsessed with "car phones."

They figured that if you were moving, you were in a vehicle. They had the "High Capacity Mobile Telephone System" in the works, which used a few high-powered towers to cover entire cities. It was clunky. It was limited. Only a few dozen people could use it at once in a whole city because the frequencies would overlap and jam.

Motorola's big gamble was "cellular" architecture.

The idea—originally dreamed up by Douglas Ring and W. Rae Young at Bell Labs back in 1947—was to divide a city into "cells." Each cell would have its own low-power tower. As you moved, your call would "hand off" from one tower to the next. Motorola took Bell Labs' theoretical idea and actually miniaturized the hardware to make it work in a hand, not a trunk.

The Specs of the Original "Brick"

Let’s talk about how bad this phone actually was by today's standards.

📖 Related: How Old is the Planet Saturn: The Gas Giant’s Chaotic History Explained

- Weight: 2.5 lbs (about the weight of a liter of water).

- Talk time: 20 to 30 minutes.

- Charge time: 10 hours.

- Price: When it finally hit the market in 1983, it cost $3,995.

Adjusted for inflation today? That's over $11,000. You could buy a decent used car for the price of one phone that could barely last through a lunch meeting before dying.

But it didn't matter. It was freedom. Before this, you were tethered to a wall by a literal copper cord. The DynaTAC was the first time a human being could walk down the street and communicate with the rest of the planet simultaneously.

The Decade of Red Tape

If the phone was invented in 1973, why didn't anyone have one until the 1980s?

The government.

The FCC spent ten years arguing over who should get the radio spectrum. AT&T fought tooth and nail to keep Motorola out. They wanted the monopoly. It wasn't until the early 80s that the regulations finally cleared, allowing the DynaTAC 8000X to be commercially released.

During those ten "lost years," Motorola spent nearly $100 million developing the tech without a single dollar of revenue coming in from it. It was a massive risk that almost bankrupted them. If the FCC had ruled differently, we might have been stuck with car-only phones for another twenty years.

Common Misconceptions: Who Didn't Invent It?

You’ll sometimes hear names like Alexander Graham Bell or Nikola Tesla in this conversation.

Bell invented the telephone, obviously, but he died decades before the first radio-phone call. Tesla predicted a "world system" of wireless communication in 1901, which was spooky-accurate, but he never built a phone.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened When Did the Titan Implode and Why We Can’t Forget It

Another name that pops up is Hedy Lamarr. The Hollywood actress actually co-invented frequency hopping, which is the backbone of modern Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. She’s a legend, and her work is why your phone doesn't drop calls constantly, but she didn't invent the "cell phone" device itself.

How to Verify the History Yourself

If you’re ever in Washington D.C., you can actually see the original prototypes. The Smithsonian Institution holds a lot of the early Motorola hardware.

You can also look up the original patent: US Patent 3,906,166, filed by Martin Cooper et al. in 1973. It's titled "Radio telephone system." Reading it is a trip—it describes a world we now take for granted, but at the time, it sounded like pure science fiction.

What This Means for Us Now

Understanding who invented the first mobile cell phone isn't just about trivia. It’s about the shift from "place" to "individual."

Before the DynaTAC, your identity was tied to your location. If you weren't at home, you didn't exist to the outside world. Cooper and his team changed the human condition. They made us reachable anywhere.

That's a double-edged sword, right? Now we can never escape work, our families, or spam callers. But that 1973 walk down Sixth Avenue started it all.

Actionable Next Steps to Explore This History

- Check the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA): They often feature the DynaTAC in their design collections. It’s worth seeing the evolution of the "user interface" from a literal keypad to a piece of glass.

- Read "Cutting the Cord": This is Martin Cooper’s autobiography. It’s surprisingly gritty and goes deep into the corporate warfare between Motorola and the FCC.

- Explore the "Cellular" Concept: If you're a tech nerd, look into how "handover" protocols work. It’s the most impressive part of the invention—the fact that your phone can switch towers at 70 mph without dropping your voice.

- Look up the 1G Network: Research how the first analog networks differed from the 5G we use today. The transition from analog (which was basically just high-end walkie-talkies) to digital (2G) in the 90s was the real turning point for security and texting.

The cell phone wasn't a "discovery." It was a decade-long grind by engineers who were told there was no market for a portable phone. They proved the world wrong. Motorola's "brick" paved the way for the smartphone in your pocket right now.

Without Marty Cooper’s ego and the engineering team’s grit, we’d probably still be looking for a payphone.