Ever sat at a crossroad, staring at a glowing crimson orb, wondering why on earth we chose red? It feels universal. You stop at red. You go on green. But the story of who invented the red light isn't as simple as one guy having a "eureka" moment in a lab. It’s actually a messy, sometimes violent history involving exploding gas lamps, literal horse power, and a frantic need to stop trains from smashing into each other.

Honestly, if you ask most people, they’ll probably point to Garrett Morgan. He’s the name that pops up in history books most often. But that's only part of the truth. Morgan’s contribution was massive—he added the "caution" phase—but the actual red light itself? That predates him by decades. It started with the railroads. In the mid-1800s, trains were the kings of transport, and they were also incredibly dangerous. Engineers needed a way to communicate without stopping the train to chat. They looked at the maritime world and adapted what they saw. Red meant danger. It was the color of blood, sure, but more importantly, it has the longest wavelength in the visible spectrum. That means it scatters less in fog or rain. It’s the easiest color to see from a distance.

The British Experiment That Went Boom

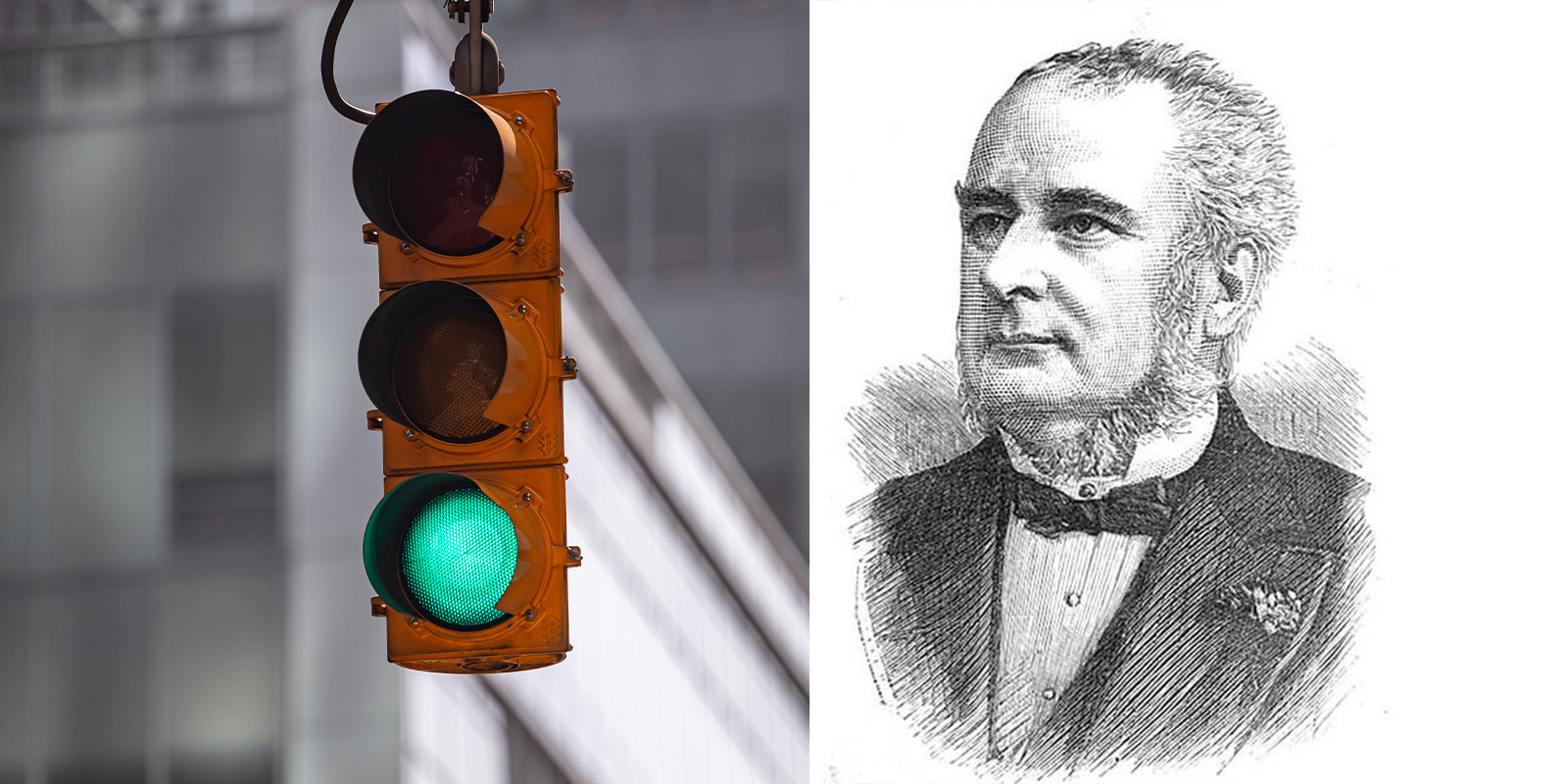

Before cars even existed, London had a massive traffic problem. We’re talking thousands of horse-drawn carriages clogging up the streets near the Houses of Parliament. In 1868, a railway signaling engineer named John Peake Knight decided to bring train logic to the streets.

He didn't use electricity.

Knight's contraption was a tall pillar with semaphore arms. During the day, the arms would swing out to tell carriage drivers what to do. At night, it used gas-powered lamps. A red light meant stop. A green light meant caution. (Wait, green for caution? Yeah, the colors weren't standardized yet). It worked great for exactly one month. Then, a leak caused the whole thing to explode in a policeman’s face. The project was scrapped immediately. Londoners went back to shouting at each other in the mud, and the idea of a mechanical traffic light went dormant for nearly fifty years.

America Takes the Reins

Fast forward to the early 1900s. Henry Ford’s Model T is everywhere. Cities like Detroit and Cleveland are becoming chaotic nightmares of pedestrians, horses, and noisy cars. The "stop-and-go" system was handled by brave (or crazy) police officers standing in the middle of intersections waving their arms.

In 1912, a cop in Salt Lake City named Lester Wire built a wooden box with two colored lights. He dipped the bulbs in red and green paint. It looked like a birdhouse, honestly. Wire didn't bother patenting it because he was more interested in public safety than money. But then came James Hoge. In 1914, Hoge installed the first "official" electric traffic signal in Cleveland, Ohio. It was still just red and green. It had a buzzer that sounded before the light changed, which sounds annoying but was actually pretty smart for the time.

Then we get to the big name: Garrett Morgan.

Morgan was an incredible inventor—the son of formerly enslaved parents who became a self-made millionaire. He saw a horrific accident between an automobile and a horse carriage. He realized that the jump from "Stop" to "Go" was too abrupt. There was no transition. In 1923, Morgan patented a T-shaped signaling device that featured a third position. This eventually became the yellow light we know today. While he didn't "invent" the red light itself, he invented the flow of modern traffic. He later sold his patent to General Electric for $40,000, which was a fortune back then.

Why Red? The Science of Wavelengths

We take it for granted, but the choice of red is deeply rooted in physics. If you want to get technical, light is just an electromagnetic wave. Red light has a wavelength of roughly 620 to 750 nanometers.

Why does this matter?

Because of Rayleigh scattering. When light hits particles in the air—like dust, water vapor, or smog—it bounces around. Shorter wavelengths (like blue and violet) scatter easily. That’s why the sky is blue. Red light, with its long, lazy waves, punches through the atmosphere with much less interference. If you’re a train engineer in 1850 or a distracted driver in 2026, you can see a red light much further away than a blue one.

Who Invented the Red Light: The Multi-Part Answer

If you're looking for a single name to win a trivia night, you’re going to have a hard time because the invention happened in stages:

- John Peake Knight (1868): The first gas-powered signal. He's the "grandfather" of the concept, even if his invention blew up.

- Lester Wire (1912): The first to use electricity for a red-green system.

- James Hoge (1914): Created the first municipal electric system that actually stayed in use.

- William Potts (1920): A Detroit police officer who figured out how to make a four-way signal using railroad lights. He's the guy who first used three colors (red, amber, green) in a single unit.

- Garrett Morgan (1923): The man who standardized the "caution" phase, making the red light actually safe for high-speed traffic.

It's kind of a collaborative effort across decades. Nobody owns the red light entirely. It was a communal response to the terrifying realization that humans are really bad at not crashing into things.

The Problem With Green

Here’s a weird fact: Green wasn't always "Go." In the early days of railroads, white was actually the signal for "Go."

✨ Don't miss: How to Turn the Torch Off on Any Device and Why Your Battery is Dying So Fast

This was a disaster.

One night in 1914, a red lens fell out of a signal lantern on a train track. Because the lens was gone, the white light of the flame shone through. The engineer thought he had a "clear" (white) signal and kept full steam ahead. He crashed. After that, the industry decided that green—which is also easily distinguishable from red—would be the "Go" signal. White was banned because it was too easily confused with street lamps or stars.

Cultural Evolution of the Stop Signal

The red light has become more than just a tool; it’s a psychological anchor. It represents the boundary between order and chaos. In the 1920s, people actually fought against traffic lights. They saw them as an infringement on their "freedom" to drive however they wanted. Sound familiar? There were protests. People ignored them. It took a massive public education campaign to get people to respect the red light.

Today, we’re seeing another shift. Smart cities are using AI to adjust the timing of red lights based on real-time traffic flow. We have "smart" intersections that can talk to autonomous vehicles. Even so, the core tech—the red light—remains unchanged. Even as we move toward self-driving cars that communicate through invisible data packets, we still keep the physical red light. Why? Because humans still need a visual fail-safe.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Driver

Understanding the history is fun, but living with red lights is a daily reality. Here is how you can actually use this knowledge to be a better, more efficient driver:

- The 3-Second Rule: Most yellow lights are timed for roughly 3 to 5 seconds. If you are more than 100 feet from the intersection when it turns yellow, the red light is inevitable. Don't floor it; the physics of the red light's wavelength won't save you from a T-bone collision.

- Sensors and Magnets: Many red lights are triggered by induction loops (wires buried in the pavement). If you're on a motorcycle or a bicycle and the light won't change, make sure you are positioned directly over the cut lines in the asphalt. That's where the sensors "feel" your metal.

- The "Red Light" of Burnout: On a metaphorical level, the invention of the red light was about survival. If you feel like your life is moving too fast, remember Garrett Morgan's "caution" light. We wasn't just trying to stop cars; he was trying to create a buffer. Take the buffer.

The red light is a masterpiece of simple engineering. It’s a mix of Victorian gas-lamp dreams, 1920s grit, and basic light physics. Next time you're stuck at a long left-turn signal, just think about John Peake Knight’s exploding gas lamp. Suddenly, waiting 60 seconds for a modern LED bulb doesn't seem so bad.

To dive deeper into how traffic systems are evolving, you can check out current Department of Transportation (DOT) standards for "Adaptive Signal Control Technology." It’s the next logical step in the story that started with a simple red lens on a foggy London night.