Ask anyone on the street and they’ll give you the same name: the Wright brothers. It’s the standard answer in every textbook. On December 17, 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright finally got their Flyer off the ground at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. It lasted twelve seconds. But if you start digging into the actual logs of aviation history, you realize that "who made airplanes first" isn't a simple trivia question with a single name attached to it. It’s a messy, decades-long brawl involving eccentric gliders, steam-powered failures, and a very angry Brazilian named Alberto Santos-Dumont.

History isn't a straight line. It’s a chaotic web of people trying not to die while falling from the sky.

Before the Wrights even touched a propeller, people were already obsessed. Sir George Cayley, an English baronet, basically figured out the physics of flight back in 1799. He’s the guy who realized you needed a fixed wing, a cockpit, and a tail. He even scratched the fundamentals of lift, weight, thrust, and drag onto a silver disk. Without Cayley, the Wrights would’ve just been two guys in Ohio selling bicycles.

The Glider King and the Death of Lilienthal

Otto Lilienthal is probably the most important person you’ve never heard of. He was a German engineer who actually flew. Not with an engine, but with gliders that looked like giant bat wings. Between 1891 and 1896, he made over 2,000 flights.

He was a rockstar.

He proved that if you shaped a wing correctly—specifically a curved or "cambered" wing—you could actually stay up there. The Wright brothers studied his data religiously. Then, in 1896, Lilienthal’s glider stalled. He fell 50 feet and broke his spine. His last words were reportedly, "Sacrifices must be made."

That’s heavy. But his data lived on.

Lilienthal’s death was the catalyst for the Wrights. They realized that the problem wasn't just lift; it was control. If you can’t steer the thing, you’re just a passenger in a very expensive lawn ornament. They focused on "wing-warping," a way to twist the wings to bank the plane. This was their "Aha!" moment.

What Really Happened at Kitty Hawk

The 1903 flight was actually kinda pathetic by modern standards. The first flight covered 120 feet. That’s shorter than the wingspan of a Boeing 747. Most people at the time didn’t even believe it happened. The Wrights were famously secretive, almost paranoid. They didn't want people stealing their patents, so they didn't do public demonstrations for years.

This secrecy created a vacuum.

🔗 Read more: USS Ronald Reagan: Why This Floating City Still Dominates the Pacific

While the Wrights were tinkering in North Carolina, Europe was moving fast. By the time the Wrights finally showed off their plane in France in 1908, the public was skeptical. They thought the Americans were bluffing.

The Brazilian Contender: Santos-Dumont

In Brazil and much of France, if you ask who made airplanes first, they won't say the Wright brothers. They’ll say Alberto Santos-Dumont.

He was a wealthy, dapper aviator who lived in Paris. He used to fly his personal dirigible (a small blimp) to cafes and tie it to lampposts while he grabbed an espresso. In 1906, he flew his 14-bis airplane in front of a massive crowd in Paris.

Here is the kicker: Santos-Dumont’s plane had wheels.

The Wright Flyer used a launching rail and a catapult system. Critics of the Wrights—mostly Europeans—argued that if you need a catapult to get in the air, you haven't really "flown." They argued that a true airplane should take off under its own power. Santos-Dumont did exactly that. He took off, flew 200 feet, and landed, all without a headwind or a track. For a long time, the Aero-Club de France officially recognized him as the first.

The Smithsonian Scandal and Glenn Curtiss

You can't talk about who made airplanes first without mentioning the massive beef between the Wrights and the Smithsonian Institution.

The Smithsonian originally claimed that their former secretary, Samuel Langley, had built the first "man-carrying" airplane capable of flight. Langley’s "Aerodrome" had actually crashed into the Potomac River twice in 1903, just days before the Wrights succeeded.

To prove the Wrights weren't first, the Smithsonian let a guy named Glenn Curtiss—the Wrights' biggest rival—tinker with Langley’s old crashed plane. Curtiss made over 90 changes to the design to make it actually flyable, then flew it in 1914. The Smithsonian then claimed this proved Langley could have flown first.

It was a total setup.

Orville Wright was so furious that he sent the original 1903 Flyer to a museum in London. He refused to bring it back to America until the Smithsonian admitted the truth. It took until 1942 for the Smithsonian to finally back down and acknowledge the Wrights. The plane didn't come home until after Orville died.

📖 Related: Why Google Doesn't Go Past 2023 for Some Users and What's Actually Happening

Why the Definition of "First" Matters

When we talk about who made airplanes first, we have to define what an airplane is. Is it a glider? Is it a steam-powered boat with wings?

- Clément Ader (1890): His bat-winged Éole supposedly hopped off the ground for 160 feet. But it had no control system. It was basically a very lucky jump.

- Gustave Whitehead (1901): Some folks in Connecticut swear Whitehead flew a powered plane two years before the Wrights. There’s a famous blurry photo, but most historians think it's a hoax or a misunderstanding.

- The Wrights (1903): They get the credit because they achieved the "Holy Trinity" of flight: it was powered, it was controlled, and it was sustained.

The "controlled" part is the big one. They figured out how to fly in three dimensions: pitch, roll, and yaw. Without that, you're just a projectile.

Technical Nuances That Most People Miss

The Wrights’ real genius wasn't the engine. Their engine was actually pretty weak—about 12 horsepower. Their real breakthrough was the propeller.

Before them, people thought propellers should work like screws in water. The Wrights realized a propeller is actually just a rotating wing. They spent months testing shapes in a homemade wind tunnel made out of a starch box. That wind tunnel data is what actually won them the sky.

They were scientists, not just mechanics.

Wilbur Wright once said that if you are looking for perfect safety, you will do well to sit on a fence and watch the birds. But if you really want to learn, you must mount a machine and become acquainted with its tricks by actual trial.

How to Explore Aviation History Yourself

If you want to see the receipts for yourself, don't just take a textbook's word for it. There are specific places where the evidence is laid bare.

💡 You might also like: Why Monkey App Porn Telegram Links Are a Massive Security Risk

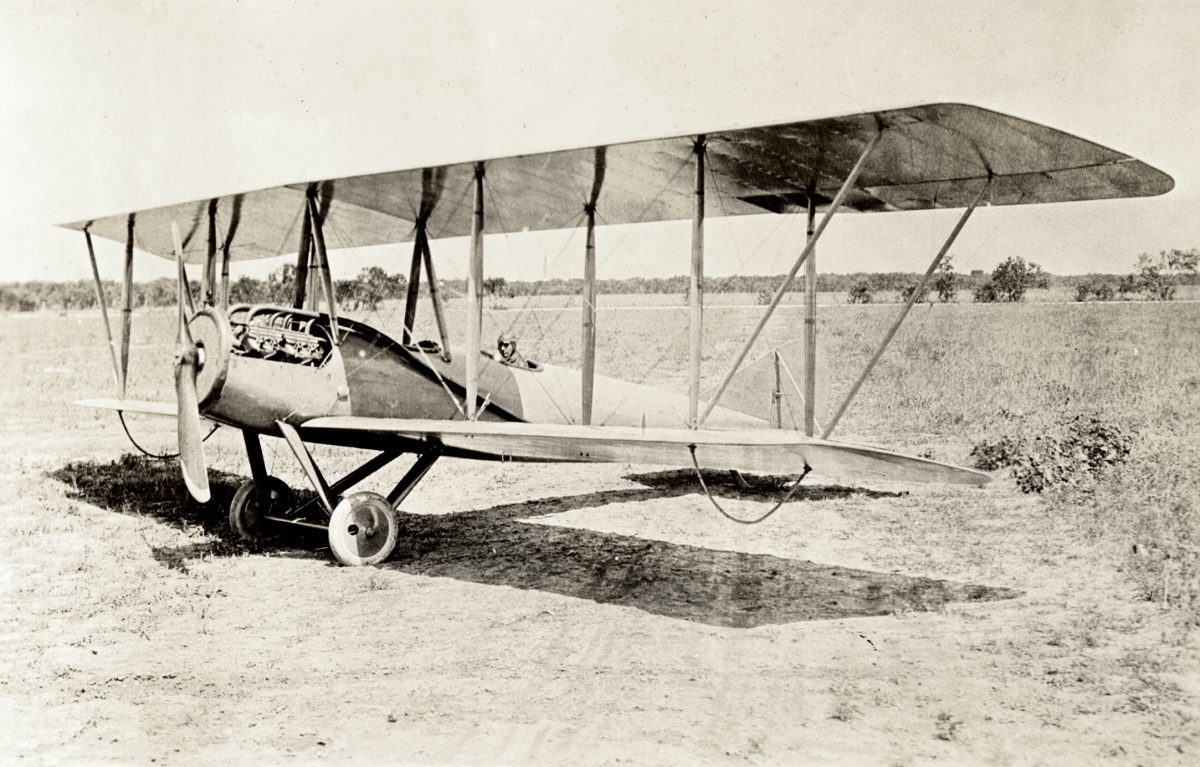

- Visit the National Air and Space Museum: The 1903 Wright Flyer is in Washington, D.C. Look at the "wing warping" wires. It’s essentially a giant kite made of spruce and muslin.

- Compare the Designs: Look up the 14-bis and the Wright Flyer. The 14-bis looks like a stack of box kites. The Wright Flyer looks like a modern biplane. You can see how the two different schools of thought—European vs. American—competed to solve the same problem.

- Read the Papers: The Library of Congress has the Wright brothers' diaries digitized. You can read their frustration when their propellers snapped or when the weather wouldn't cooperate.

The reality is that "who made airplanes first" is a collective achievement. The Wrights crossed the finish line, but they were running on a track built by Lilienthal, Cayley, and Chanute. It was a global race. The Wrights won on technicality and control, but the spirit of flight belonged to dozens of people who were willing to risk their necks to see what the clouds looked like from above.

If you’re researching this for a project or just curiosity, focus on the 1890–1910 window. That’s where the real drama is. Look into the "Patent Wars" that followed 1903; it actually slowed down American aviation so much that by World War I, American pilots had to fly French planes because the Wrights were too busy suing everyone to actually innovate.

History is never as clean as the statues make it look. It’s built on bicycle parts, broken gliders, and a whole lot of stubbornness.