Ask ten different people who was the first computer inventor and you’ll get ten different answers. Some will swear it was Charles Babbage. Others will point to Alan Turing or maybe that guy from Germany you’ve never heard of, Konrad Zuse.

Honestly? They’re all kind of right.

The problem is that we don't really agree on what a "computer" actually is. Are we talking about a pile of brass gears that can do addition? Or does it have to have electricity? Does it need a screen? If you mean a machine that can take a set of instructions and churn out an answer, the story starts way earlier than most people think.

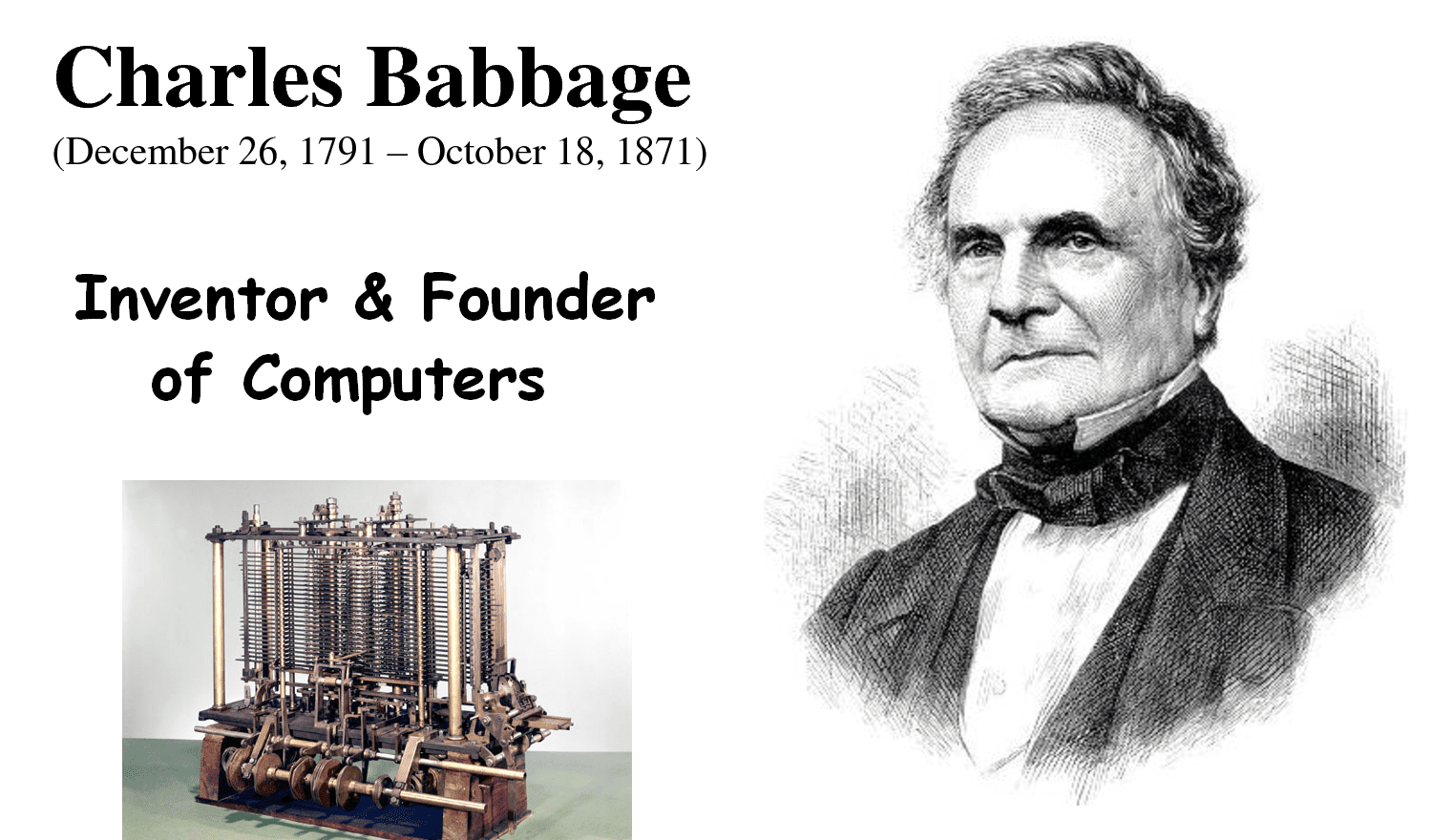

The Victorian math genius who never finished his project

If you want to be a purist about the "first" person to conceive of the modern computer, you have to talk about Charles Babbage. Back in the 1830s, while everyone else was riding around in horse-drawn carriages, Babbage was designing the Analytical Engine. This wasn't just a calculator. It had a "mill" (a CPU) and a "store" (memory). It used punch cards, which is exactly how IBM was doing things over a century later.

Babbage was a bit of a character. He was brilliant, sure, but he was also notoriously cranky and terrible at managing money. He never actually finished building the Analytical Engine because the British government eventually got tired of throwing money at him. He died with only a few fragments of his machine completed.

But here’s the thing: his designs worked. In 1991, the London Science Museum built a version of his earlier "Difference Engine No. 2" using his original specs. It worked perfectly. If Babbage had the funding and the manufacturing precision of the 20th century, the digital age might have started in the 1840s.

The woman who saw the future

You can’t talk about Babbage without mentioning Ada Lovelace. She was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, and she was a mathematical prodigy. While Babbage was focused on the hardware, Lovelace was thinking about what the machine could actually do. She wrote what is widely considered the first computer program—an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

📖 Related: How Jensen Huang Made Nvidia the Most Important Company in the World

Lovelace realized something Babbage didn't quite grasp: these machines could do more than just math. She speculated that if you could represent music or art as symbols, the machine could "compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent." She basically predicted MIDI and Photoshop in 1843.

The German engineer in the living room

While the Brits usually claim the title, there’s a very strong case for Konrad Zuse being the real first computer inventor. In 1938, in his parents' living room in Berlin, Zuse built the Z1. It was a mechanical monster that used binary logic.

Binary is the "1s and 0s" language computers use today. Babbage used decimal (0-9), which is way more complicated for a machine to handle. Zuse figured out that binary was the secret sauce.

By 1941, he finished the Z3. This was a massive milestone. It was the first functional, fully automatic, programmable digital computer. It didn't use electronic vacuum tubes yet—it used telephone relays—but it worked. Unfortunately for Zuse, he was working in Nazi Germany. His work was largely ignored by the government, and his original machines were destroyed during Allied bombing raids. Because he was isolated by the war, his breakthroughs didn't influence the American and British scientists who usually get the credit.

The vacuum tube revolution and the "Giant Brain"

If your definition of a computer requires it to be electronic, then the title of first computer inventor shifts again. This brings us to the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer).

Developed at the University of Pennsylvania by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, ENIAC was a beast. It filled a 30-by-50-foot room, weighed 30 tons, and used about 18,000 vacuum tubes. When they turned it on, the lights in Philadelphia supposedly flickered.

It was built to calculate artillery firing tables for the Army during World War II. It was fast—thousands of times faster than anything mechanical. But it had a huge flaw: you had to physically rewire the machine to change its program. It wasn't "stored program" in the way we think of today.

The Atanasoff-Berry dispute

For a long time, Mauchly and Eckert held the patent for the electronic digital computer. But in 1973, a federal judge threw it out. Why? Because it turned out they had "derived" some of their ideas from a guy named John Atanasoff.

Atanasoff and his student Clifford Berry built the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) at Iowa State College between 1937 and 1942. It was much smaller than ENIAC and couldn't be reprogrammed, but it was the first to use vacuum tubes for digital math. The court ruling officially named Atanasoff the inventor of the electronic digital computer, but most people still haven't heard of him.

The codebreakers and the father of AI

We also have to talk about Alan Turing. During World War II, Turing worked at Bletchley Park to crack the Nazi Enigma code. He didn't build a general-purpose computer in the sense of a PC, but his "Bombe" machines and the later "Colossus" (built by Tommy Flowers) were pivotal.

More importantly, Turing gave us the theoretical framework. His 1936 paper introduced the "Universal Turing Machine." He proved that a machine could be built to solve any problem that could be described by an algorithm. He wasn't just building a box; he was defining the soul of the computer.

Why it actually matters

Tracing who was the first computer inventor isn't just a trivia game. It shows us how innovation actually happens. It’s never one person in a vacuum. It’s a messy, overlapping web of ideas.

Babbage had the logic.

Lovelace had the vision.

Zuse had the binary.

Atanasoff had the electronics.

Turing had the theory.

Mauchly and Eckert had the scale.

If any one of these people hadn't existed, your smartphone would look very different—or it wouldn't exist at all.

Understanding the timeline

To keep it simple, think of the evolution like this:

- 1830s: The "Mental" Birth (Babbage/Lovelace). The designs were there, but the tech wasn't.

- 1930s: The "Binary" Birth (Zuse/Atanasoff). The shift from gears to logic and electricity.

- 1940s: The "Power" Birth (ENIAC/Colossus). The scale goes from "garage project" to "government priority."

- 1950s: The "Stored Program" Birth (EDVAC/Manchester Baby). This is where computers finally became "easy" to use because they could store software in memory.

Moving beyond the history books

If you're researching this for a project or just because you’re a nerd for tech history, don't stop at the big names. The story of the computer is also the story of the "human computers"—mostly women—who did the math by hand before the machines took over. People like Katherine Johnson or the "ENIAC Girls" (Kathleen McNulty, Jean Bartik, etc.) were the ones who actually made these early machines functional.

To get a real feel for how this evolved, you should look into the history of the transistor. The vacuum tubes used by the "first" inventors were hot, fragile, and constantly breaking. When Bell Labs invented the transistor in 1947, that’s when computers stopped being room-sized monsters and started becoming the tools we carry in our pockets.

Check out the "Computer History Museum" archives online if you want to see the actual blueprints of the Z3 or the Analytical Engine. Seeing the physical complexity of Babbage’s drawings compared to the simplicity of modern code is a wild experience.

Read up on the von Neumann architecture. It’s the specific blueprint that almost every computer today follows. Understanding why we still use the same basic setup from the 1940s will tell you more about the future of tech than any history book.

Basically, the "first" inventor depends on where you draw the line. But if you want to be technically accurate in a conversation: Babbage invented the concept, Zuse built the first working programmable machine, and Atanasoff pioneered the electronics. Just don't expect a short answer at a party.