You’ve probably seen those weird, neon-colored plastic violins on YouTube. They look like props from a low-budget sci-fi flick. For a long time, that’s basically all they were—novelties that sounded like a cat trapped in a Tupperware container. But things changed. Honestly, the gap between "toy" and "tool" has closed so fast that professional orchestras are starting to take notice.

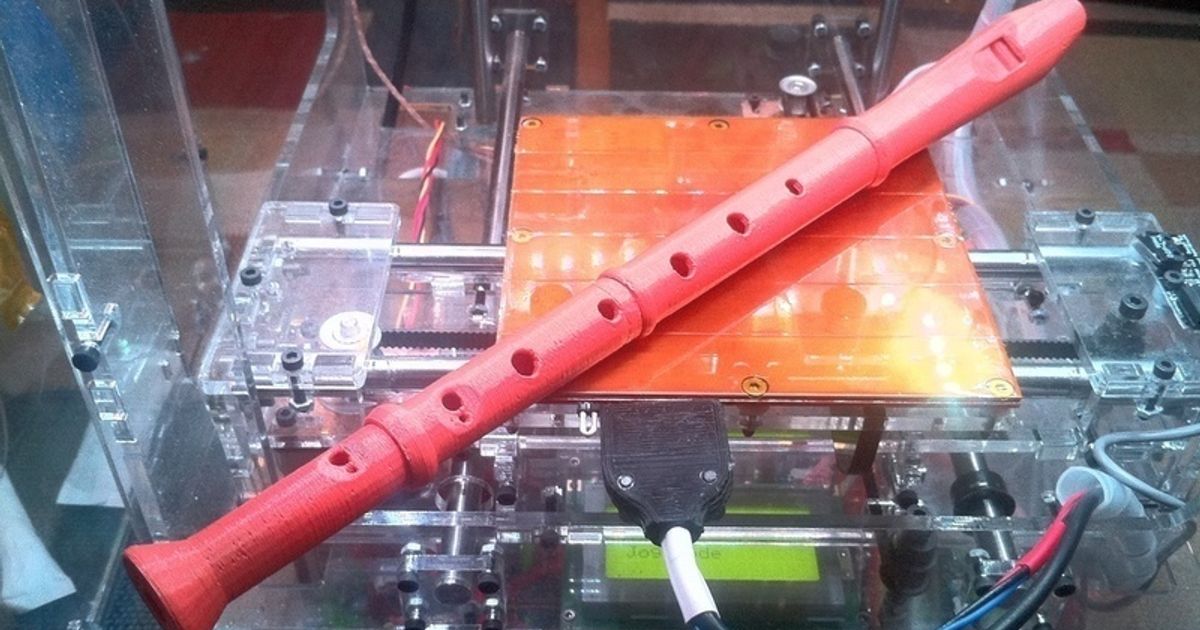

3D printed musical instruments aren't just about making cheap gear. It's about geometry that was literally impossible to carve out of wood or cast in brass ten years ago.

Think about a traditional flute. To make one, you need a highly skilled artisan drilling precise holes into a tube. If they mess up by a fraction of a millimeter, the whole thing is scrap. With additive manufacturing, you’re not fighting the material. You’re just telling a laser or an extruder exactly where the molecule belongs. This shift is turning the music industry upside down, and not everyone is happy about it.

The Sound Quality Myth

Let’s address the elephant in the room: tone. If you ask a purist, they’ll tell you that "plastic" can’t resonate like aged spruce or maple. They’re partially right, but they’re also missing the point.

Sound is physics.

When you play a violin, the string vibrates, the bridge transfers that energy to the body, and the air inside the box moves. Traditional wood is unpredictable. It has grain, knots, and varying density. A 3D printed musical instrument made from carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers or high-grade resins can be engineered for perfect consistency.

Monad Studio created a 2-string piezoelectric violin that looks more like a skeletal spine than a musical instrument. It doesn't try to sound like a Stradivarius. It sounds like something entirely new. It’s haunting. It’s metallic. It’s loud.

Researchers at the University of Sheffield have been diving deep into how different infill patterns—the internal "honeycomb" inside a 3D print—affect acoustics. By changing the density of the plastic inside the walls of a guitar, you can technically "tune" the resonance of the body itself. You can't do that with a solid block of mahogany.

What’s Actually Working Right Now?

It’s not all experimental art. Some of this stuff is incredibly practical.

- Brass Mouthpieces: This is the biggest "quiet" revolution. Professional trumpet and trombone players are using 3D printed mouthpieces made from medical-grade titanium or silver-plated resins. Why? Because you can scan a vintage, one-of-a-kind mouthpiece and replicate its internal geometry perfectly. If you lose your favorite $500 mouthpiece on tour, you just print another one.

- The Hovalin: Created by Matt and Kaitlyn Hova, this is a functional, 3D printable violin designed to be accessible. It’s used in STEM programs globally. It costs a fraction of a student wood violin and, honestly, sounds surprisingly decent for something you made in your garage.

- Travel Guitars: Companies like KLOS and various open-source projects on Thingiverse have proven that a 3D printed guitar body is nearly indestructible. You can leave it in a hot car or take it on a plane without worrying about the wood cracking.

- Woodwind Keywork: High-end clarinets are starting to see 3D printed keys. Traditional casting is expensive and heavy. Printed titanium keys are lighter and allow for faster finger action.

Why 3D Printed Musical Instruments Are Better for Your Body

Ergonomics in music is usually an afterthought. We’ve been forcing our bodies to adapt to shapes designed in the 1700s.

Ever seen a bassoon? It’s a logistical nightmare for the human hand.

Laurent Bernadac’s 3Dvarius is a prime example of changing the form factor. Because it's printed using Stereolithography (SLA), the weight is distributed in a way that reduces neck strain for the performer. Since the material is lighter than traditional wood and hardware, you can play a four-hour set without needing a chiropractor the next morning.

We are seeing a rise in "bespoke" instruments. Imagine a flute where the keys are spaced exactly to the length of your fingers. For musicians with arthritis or limb differences, this isn't just a cool gadget—it’s the only way they can keep playing.

The Cost Factor: Disrupting the Gatekeepers

A decent student cello costs $2,000. A professional one? You're looking at the price of a mid-sized SUV.

This creates a massive barrier to entry. 3D printed musical instruments are democratizing high-quality sound. You can buy a high-end 3D printer for $500 today. The raw filament might cost $30. While you still need strings, tuning pegs, and a bow, the "body" of the instrument becomes nearly free.

This terrifies some manufacturers. But for a kid in a neighborhood with no arts funding, a printed violin is a lifeline.

It’s not just about being cheap, though. It’s about rapid prototyping. If a luthier wants to try a new f-hole design on a violin, it used to take weeks of carving. Now, they can print three different versions in a weekend, test the acoustics, and refine the design by Monday.

The Limitations (Because It's Not All Perfect)

We have to be real here. 3D printing isn't a magic wand.

Most "home" printers use FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling), which leaves layer lines. These lines can be acoustic disasters if not handled correctly. They create friction for the air moving inside a wind instrument. You have to sand them, coat them, or use chemical vapor smoothing to get the surface finish required for a professional sound.

💡 You might also like: Why You Can't Turn Off Find My iPhone and How to Actually Fix It

Then there’s the "creep" issue. Plastic, under the constant tension of guitar or violin strings, likes to bend over time. If you don't reinforce the neck with a steel or carbon fiber rod, your 3D printed guitar will eventually turn into a banana.

And heat? Don't leave a PLA (Polylactic Acid) printed instrument in a sunny window. It will warp. It will melt. It will become a very expensive piece of modern art. Professional-grade printed instruments usually use PETG, ABS, or high-performance resins to avoid this, but those are harder to work with.

Where the Industry Goes Next

We’re moving toward hybrid instruments.

The most successful builders aren't trying to print the whole thing. They’re using 3D printing for the complex, organic shapes—the body, the internal bracing, the custom grips—and combining them with traditional wooden necks or carbon fiber fretboards.

Keep an eye on companies like LAVA Music. While they use injection molding rather than "printing" for their mass-market stuff, the design language is heavily influenced by the generative design found in 3D printing circles.

📖 Related: Is it a joke? The /t meaning tone tag and why it keeps you from getting canceled

Also, look at the work of Dr. Ricardo Simian. He’s been 3D printing historical instruments like the cornett (a cross between a trumpet and a recorder) using wood-fill filaments. These instruments are notoriously difficult to play and even harder to build. 3D printing has brought an extinct sound back to life.

Getting Started: Actionable Steps for Musicians

If you’re curious about jumping into this world, don't just go out and buy a printer and expect a concert-ready cello by Tuesday. Start small and scale up.

- Start with Accessories: Print a personalized guitar pick, a custom shoulder rest for a violin, or a wall mount. It gets you used to how the materials feel.

- Use the Right Material: Forget PLA for anything under tension. Look into Carbon Fiber PETG or ASA. These materials handle the stress of strings and the heat of a stage much better.

- Check the "Hovalin" Files: If you want to build a full instrument, start with the Hovalin. The documentation is excellent, and there’s a massive community to help you when your print fails at 3:00 AM.

- Focus on the "Post-Process": The secret to a good 3D printed musical instrument is the work you do after the print is finished. Sanding, sealing, and proper assembly are 90% of the battle.

- Don't Ignore the Hardware: A 3D printed guitar body with $10 pickups will sound like garbage. Use the money you saved on the body to buy high-end electronics, strings, and bridges.

The future of music isn't just about what we play; it's about how we build the tools to play it. We are moving away from a world where you have to fit the instrument, and toward a world where the instrument is built to fit you.