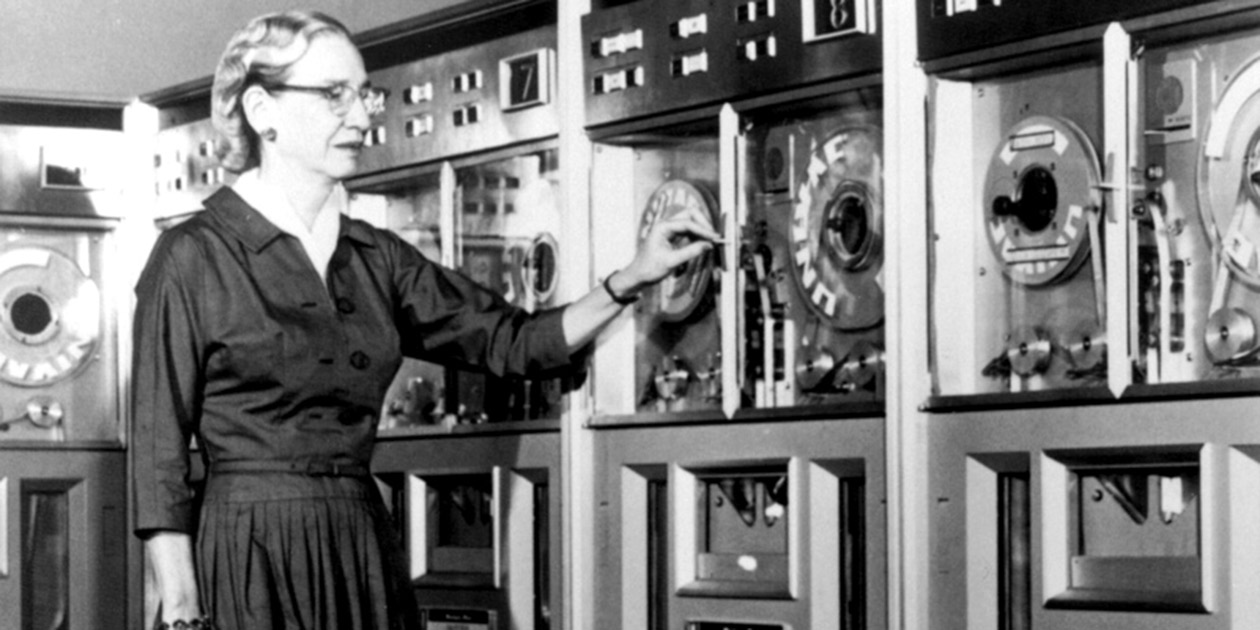

You’ve probably heard the "moth in the relay" story a thousand times. It’s the classic bit of tech folklore where a literal bug crawled into a Harvard Mark II computer in 1947, got stuck, and crashed the system. Grace Hopper taped it into a logbook. Everyone laughs. It’s a great anecdote. But honestly? Reducing the career of computer science Grace Hopper to a story about a moth is like saying Albert Einstein was "that guy who forgot to brush his hair." It misses the point.

Hopper didn't just find a bug. She basically invented the idea that humans shouldn't have to speak "machine" to get things done.

Before her, if you wanted a computer to do something, you had to be a mathematical wizard. You were writing in octal or hexadecimal code. You were toggling switches. It was tedious, prone to error, and frankly, inaccessible to anyone without a PhD in mathematics. Hopper looked at that mess and decided that we should be able to talk to computers in English. People thought she was crazy. They told her computers didn't understand English. She did it anyway.

👉 See also: Reverse Phone Number Look Up: Why You Keep Getting Scam Results and How to Actually Find Someone

The Compiler: The Invention Nobody Wanted

In 1951, Hopper developed the A-0 System. It was the first compiler. Now, if you’re a dev today, you use compilers or interpreters every five seconds without thinking. But back then? The establishment hated it.

The prevailing wisdom was that computers were high-end calculators. The idea that a program could write another program was seen as an unnecessary layer of abstraction. "Subroutines are for people who can't handle the math," was the vibe. Hopper ignored the critics. She realized that if we wanted computing to scale, we needed to automate the translation from human-readable logic to machine-executable bits.

Without the foundation laid by computer science Grace Hopper, we wouldn't have Python. We wouldn't have C++. We’d likely still be hand-optimizing assembly for every specific piece of hardware we owned. She saw the compiler not as a tool for "lazy" programmers, but as a way to democratize information.

FLOW-MATIC and the Birth of COBOL

By the mid-50s, Hopper created FLOW-MATIC. It was the first programming language to use English-like commands (think "FLOW" or "COUNT"). This wasn't just a technical achievement; it was a philosophical shift. She wanted the business world to use computers, not just the military and academia.

This eventually led to the creation of COBOL (Common Business-Oriented Language). While Hopper didn't write COBOL alone—it was a committee effort—her influence was the DNA of the project. If you go to a bank today and check your balance, there is an incredibly high chance that a COBOL script, running on a mainframe, is processing that transaction. It’s the "dinosaur" language that refuses to die because it was built on Hopper’s principle of readability and reliability.

💡 You might also like: Adding Cash to Cash App: Why Your Money Keeps Getting Declined and How to Fix It

The "Amazing Grace" Leadership Style

Hopper wasn't just a scientist. She was a Rear Admiral in the U.S. Navy.

She had this habit of carrying around "nanoseconds"—pieces of wire about 11.8 inches long. Why? Because that’s the distance light travels in one billionth of a second. When she was explaining why satellite communications had delays, she’d hand a wire to an Admiral and say, "Here is a nanosecond." It was brilliant. It turned abstract, complex physics into something you could hold in your hand.

She was a rebel within the bureaucracy. She famously said, "It's easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission." In the rigid structure of the 1950s Navy, that was a radical stance. She believed that the most dangerous phrase in the English language was "We've always done it this way."

Think about that.

In a world of legacy systems and "best practices," Hopper was the original disruptor. She hated stagnation. She pushed for standardization because she saw that if every company had their own proprietary version of a language, the industry would fragment and fail. She forced the big players—IBM, Honeywell, Burroughs—to agree on common standards. That’s the only reason the modern web works.

Why We Still Need Her Mindset

We’re currently in the middle of an AI revolution. Everyone is talking about Large Language Models and natural language processing.

But look closely.

What is a prompt? It’s a human using English to tell a computer what to do. That is exactly what computer science Grace Hopper was shouting about in 1952. We are finally reaching the endgame of her vision. She wanted the barrier between human thought and machine execution to be zero.

We often treat history as a series of static events. Hopper wasn't just a lady in a uniform who found a moth. She was the person who understood that software is more important than hardware. She knew that the "soul" of the machine was the logic we put into it, and that logic should be accessible to everyone.

Common Misconceptions About Hopper’s Work

One thing people get wrong is the "Bug" story. While she popularized the term, she didn't actually invent it. Engineers had been talking about "bugs" in mechanical systems since the time of Thomas Edison. What Hopper did was document the first literal computer bug. It’s a nuance, but it matters. She was a meticulous record-keeper.

Another misconception? That she was just a "math person."

Actually, she was an educator. She taught at Vassar. She spent her later years traveling the world, giving lectures to young people. She didn't care about the accolades; she cared about the next generation. She famously said she wanted to live until 1999 so she could see the look on people's faces when the "Millennium Bug" (Y2K) hit, largely because she knew the short-sightedness of early coding (like using two digits for years) would come back to haunt us.

She was right, of course.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Hopper Playbook

If you want to apply the computer science Grace Hopper philosophy to your own career or tech stack, you don't need a Navy commission. You just need to stop accepting "the way things are."

Prioritize Readability Over Cleverness. Hopper pushed for COBOL because business people needed to understand what the code was doing. If you are writing code that only you can understand, you aren't being "smart," you're creating a bottleneck. Write for the human who has to maintain your work in five years.

Build for Portability. One of Hopper's biggest fights was for "Common" languages. Don't lock yourself into proprietary ecosystems if you can help it. Use open standards. Build systems that can talk to each other.

Keep Your "Nanoseconds" Handy. Find ways to explain your complex technical debt or architectural choices to non-technical stakeholders. Use physical metaphors. If you can't explain why a feature is taking three weeks in a way a CEO understands, you haven't simplified it enough.

Challenge the "Always Done It This Way" Mentality. If you see a process that is slow, bloated, or "just how we do things," audit it. Hopper’s compiler was born because she was tired of doing manual translation. Automation is the daughter of boredom and brilliance.

Focus on the Logic, Not Just the Tool. Languages change. Tools die. COBOL is still here, but the hardware it runs on has changed a thousand times. Focus on the underlying business logic and the "why" behind the code.

Grace Hopper died in 1992, but her fingerprints are on every keyboard you touch. She took the computer out of the hands of the elite and gave it to the rest of us.

🔗 Read more: Locking keyboard on Mac: The simple ways to stop accidental typing

Stay curious. Break things. Ask for forgiveness later.