Math has a funny way of making simple things look like a total nightmare. You're sitting there, staring at a page of symbols, and suddenly you hit a wall of transcendental functions. It happens to everyone. One of the most common stumbling blocks is figuring out exactly what is e ln x and why it keeps popping up in everything from financial modeling to physics homework. Honestly, it looks intimidating. You have Euler's number ($e$), which is an irrational mess of decimals, sitting right next to a natural logarithm ($ln$), which is basically the math equivalent of a mystery box.

But here is the secret: they are just undoing each other.

Think about it like this. If you take the number five, add three, and then immediately subtract three, you're back at five. No one loses sleep over that. It's basic arithmetic. In the world of higher math, $e$ and $ln$ share that same "undo" relationship. They are inverse functions. When you see the expression $e^{ln(x)}$, you aren't looking at a complex calculation. You're looking at a mathematical U-turn.

The Identity Crisis of e ln x

If we’re being precise, the rule is $e^{\ln(x)} = x$. It’s an identity. It works because the natural log is defined as the power to which you must raise $e$ to get $x$. So, if you raise $e$ to "the power you need to raise $e$ to get $x$," well, you get $x$. It's almost recursive. It’s like asking for the name of the guy named Steve.

The answer is Steve.

This isn't just a neat trick for passing a quiz. This identity is the backbone of how we solve exponential growth equations. If you’ve ever looked at a population growth chart or a compound interest spreadsheet, you’ve seen this logic in action. Mathematicians like Leonhard Euler and John Napier didn't just stumble onto these constants for fun; they were trying to find a way to make multiplication and division easier by turning them into addition and subtraction.

Why Does This Even Matter?

You might wonder why we don't just write $x$ and call it a day. Why bother with the $e$ and the $ln$ at all? The answer lies in calculus.

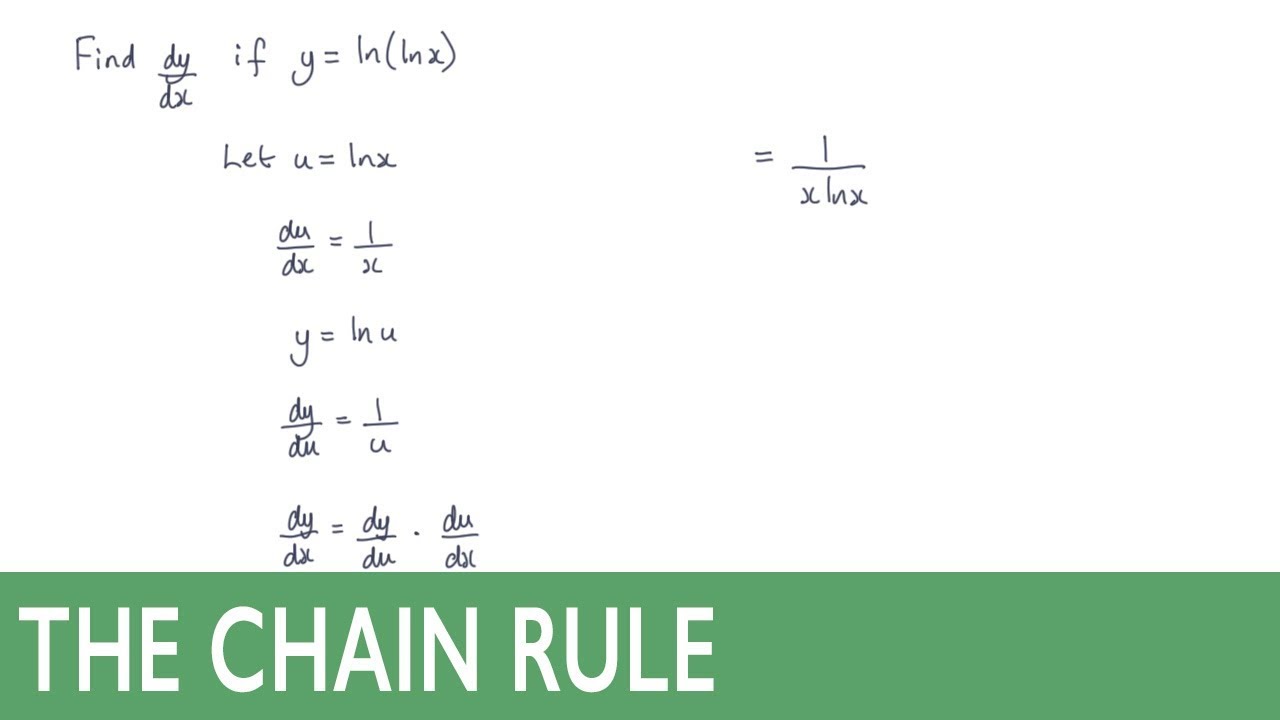

When you're dealing with derivatives and integrals, $e^x$ is the "perfect" function. Its derivative is itself. That is incredibly rare. By rewriting other functions using $e$ and $ln$, we can use the rules of calculus much more efficiently. It’s a bit like converting currency before you go on vacation. It might seem like an extra step, but once you’re there, everything runs a lot smoother.

Specifically, when we have a weird base like $3^x$, we can't easily differentiate that without a little bit of gymnastics. But if we use the property $a^b = e^{b \ln(a)}$, we can turn $3^x$ into $e^{x \ln(3)}$. Now, suddenly, we have that beautiful $e$ base that makes the math behave.

The Domain Trap

Now, don't get too comfortable. There is a catch. You can't just throw any number into e ln x and expect it to work. Math has rules, and $ln(x)$ is a bit of a diva.

✨ Don't miss: Why Gemini 3 Flash is Actually Changing How We Work

The natural logarithm is only defined for $x > 0$. You can't take the log of a negative number (at least not in the realm of real numbers), and you definitely can't take the log of zero. So, while $e^{\ln(x)} = x$ is true for all positive values, it falls apart the moment you try to use it on $-5$ or $0$.

- If $x = 10$, then $e^{\ln(10)} = 10$.

- If $x = 0.5$, then $e^{\ln(0.5)} = 0.5$.

- If $x = -2$, the expression is undefined.

It’s a small detail, but it’s the kind of thing that trips up even the smartest engineering students. You have to respect the domain.

Breaking Down the Inverse Property

To really get what is happening here, you have to look at the graphs. If you plot $y = e^x$ and $y = \ln(x)$ on the same coordinate plane, they are perfect mirror images of each other across the line $y = x$. This symmetry is the visual proof of their inverse relationship.

When you compose them—meaning you put one inside the other—they cancel out. It’s a total wash.

This works both ways, too. While $e^{\ln(x)} = x$, it’s also true that $\ln(e^x) = x$. The order doesn't change the result, though the domain rules for $\ln(e^x)$ are actually more relaxed because $e^x$ is always positive, regardless of what $x$ is. It's one of those weird nuances that makes math teachers smile and students groan.

📖 Related: The Trade Ins Twilight Zone: Why Your Old Phone Value is Vanishing

Real-World Applications You Actually Use

Believe it or not, this isn't just theoretical fluff. The relationship between $e$ and $ln$ is baked into the technology you use every day.

Take your phone's battery life, for instance. Engineers use these functions to model how the voltage drops over time. Or look at the "Undo" button in a complex piece of software. The concept of inverse operations is what allows digital systems to track and reverse changes. In data science, we often "log-transform" data to normalize it—basically squishing huge numbers down so they're easier to work with—and then use $e$ to "de-log" it back into its original form when we're done.

Without the ability to jump back and forth between these two states using what is e ln x, our ability to process large-scale statistical data would be significantly slower.

Common Misconceptions to Watch Out For

People often get $e$ mixed up with other constants like $\pi$. While $\pi$ is about circles, $e$ is about growth. It’s the "natural" rate of growth.

✨ Don't miss: Why You Can't Just Download Videos From Twitter (and How to Actually Do It)

Another mistake is thinking that $ln$ is just "log." While $ln$ is a logarithm, it is specifically base $e$. If you use a common log (base 10) on a calculator when you should have used $ln$, your result for $e^{\log(x)}$ will be a mess. It won't equal $x$. The bases must match.

The elegance of $e^{\ln(x)}$ is that the bases match perfectly.

Steps to Master This Concept

- Memorize the identity. Just accept that $e$ and $ln$ are enemies that destroy each other on sight.

- Check your $x$ value. Before you cancel them out, make sure $x$ isn't zero or negative.

- Practice rewriting. Take a function like $2^x$ and practice turning it into $e^{x \ln(2)}$. This is the single most useful skill for passing Calculus II.

- Visualize the graph. If you get stuck, remember the mirror image. If the functions don't mirror each other, they aren't inverses.

Moving Forward with Confidence

Once you stop seeing $e$ and $ln$ as scary symbols and start seeing them as a pair of keys that lock and unlock the same door, the math gets a lot easier. You don't need to be a genius to use these tools. You just need to recognize the pattern.

Next time you see an expression with $e$ raised to a natural log, don't reach for a calculator. Just look at the value inside the parentheses. That’s your answer. It’s one of the few times in math where the most complicated-looking problem actually has the simplest solution.

To truly master this, start applying the identity to more complex algebraic expressions. Try simplifying $e^{2 \ln(x)}$. Remember your log properties: that $2$ can move inside to become an exponent, making it $e^{\ln(x^2)}$. From there, the $e$ and $ln$ vanish, leaving you with just $x^2$. This process of "moving the furniture" before you cancel everything out is where the real power of logarithmic identities lies. Practice these transformations until they become second nature, and you'll find that the most daunting parts of differential equations suddenly feel like a breeze.