Biology textbooks are notorious for being pretty, but they’re also misleading. You’ve seen it a thousand times: that iconic picture of dna replication featuring a neat, colorful ladder unzipping while little blobs of protein float around like they’re in a slow-motion dance. It looks organized. It looks calm. Honestly, it looks nothing like the chaotic, high-speed reality happening inside your nuclei right now.

If your cells actually moved at the pace shown in those diagrams, you wouldn’t survive the second it took to read this sentence.

DNA replication is a brutal, mechanical necessity. Every time a cell divides, it has to copy three billion base pairs with near-perfect accuracy. To do that, the molecular machinery involved—specifically the DNA polymerase complex—has to move at speeds that would make a jet engine look sluggish. We’re talking about adding roughly 50 nucleotides per second in humans, and up to 1,000 per second in bacteria like E. coli. When you look at a static image, you miss the vibration, the heat, and the sheer tension of a strand being pulled apart at 10,000 RPM.

The Anatomy of a Picture of DNA Replication

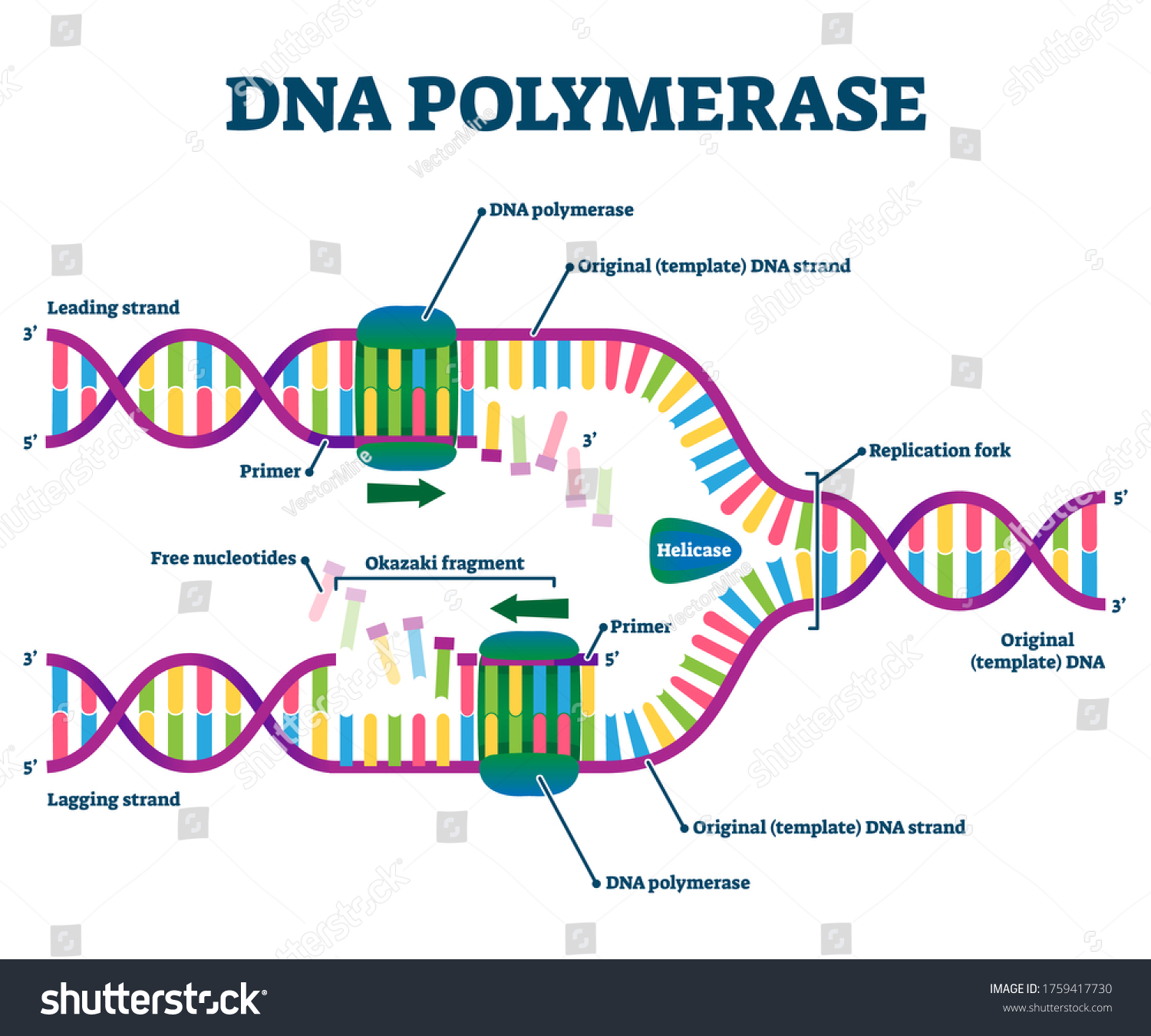

Most diagrams start with the "Y" shape. We call it the replication fork. It’s the point where the double helix is ripped open by an enzyme called helicase. Think of helicase as the world’s most efficient zipper slider, except it’s breaking hydrogen bonds rather than sliding over metal teeth.

In a standard picture of dna replication, you'll see two strands being worked on. One is the leading strand, which is the "easy" one. The polymerase just follows the helicase, trailing along like a loyal dog. But then there’s the lagging strand. This is where biology gets weird and frankly, a bit inefficient. Because DNA can only be synthesized in one direction ($5'$ to $3'$), the lagging strand has to be built backward in choppy little segments.

These are the Okazaki fragments, named after Reiji and Tsuneko Okazaki, the husband-and-wife team who discovered them in the 1960s. If you’re looking at a high-quality scientific illustration, you’ll see these fragments as little disconnected loops. It’s a messy work-around for a fundamental geometric problem. It’s like trying to pave a road while only being allowed to walk backward; you have to lay a few feet, stop, jump back ten feet, and start again.

Why Color Coding is a Lie (But a Useful One)

In a textbook, the "A" nucleotides are always green, "T" is red, "C" is blue, and "G" is yellow. Or some variation of that. In reality? DNA has no color. It’s a clear, sticky polymer. Under an electron microscope, a picture of dna replication looks like a tangled mess of grey threads.

💡 You might also like: Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant Location: Why It’s Actually In The Middle Of The Desert

The colors are there for us, not the science. They help us visualize the base-pairing rules that Erwin Chargaff first poked at before Watson and Crick took the credit for the double helix model. Without those colors, the sheer complexity of the "replisome"—the entire factory of proteins involved—would be a grey smudge.

The Parts Nobody Draws Correctly

Most people forget the "Topoisomerase." It’s a mouthful of a name, but it’s the unsung hero of the process. Imagine you have two pieces of string twisted together. If you grab them and pull them apart in the middle, the ends get tighter and tighter until they knot up. This is called supercoiling.

In a real picture of dna replication, you’d see Topoisomerase sitting ahead of the fork, literally cutting the DNA, letting it spin to relieve the pressure, and then gluing it back together. It’s a molecular surgeon. Without it, the DNA would snap under the torsional strain. If you see a diagram where the DNA ahead of the "unzipping" part looks perfectly relaxed, it’s a bad diagram.

- Helicase: The unzipper.

- Primase: The "start here" signpost. It lays down a tiny bit of RNA because DNA polymerase is a bit of a diva and can’t start a chain from scratch; it can only extend an existing one.

- DNA Polymerase: The builder. It’s the star of the show, checking for errors as it goes.

- Ligase: The molecular glue that sews the Okazaki fragments together on the lagging strand.

The scale is also usually wrong. These proteins are massive compared to the DNA strand they are "walking" on. It’s more like a freight train moving along a thread.

The Error Rate and the "Proofreader"

What’s wild is that even though this happens at breakneck speed, the error rate is incredibly low—about one mistake for every billion nucleotides added. This is because DNA polymerase has an "editing" function.

If it adds the wrong base, it feels the "clunkiness" of the fit. It’s like a key that doesn't quite turn in a lock. The enzyme actually backs up, snips out the wrong base, and tries again. Most pictures of dna replication fail to capture this "reverse gear." They make it look like a one-way street. In reality, it’s a constant process of checking, double-checking, and fixing.

Where to Find "Real" Images

If you want to see what this actually looks like, skip the clip art. Look for "Cryo-electron microscopy" (Cryo-EM) images. This technology, which won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2017, allows scientists to freeze molecules in mid-motion.

A Cryo-EM picture of dna replication shows the proteins as lumpy, textured "clouds" rather than smooth geometric shapes. You can see the actual "fingers" and "thumbs" of the polymerase gripping the DNA. It’s less like a computer chip and more like a wet, vibrating machine made of jiggling atoms.

Researchers at the University of California, Davis, even managed to film DNA replication in real-time using single-molecule imaging. They found that the two strands actually replicate at different speeds and often stop and start unpredictably. It’s not the synchronized swimming we see in animations. It’s a stuttering, chaotic, but ultimately successful race.

Why This Matters for Your Health

This isn't just academic. Most of the heavy-hitter drugs we use to fight cancer or viruses target this exact process.

📖 Related: How Much Is a Cybertruck Cost: What Owners Are Actually Paying in 2026

Chemotherapy often works by gumming up the replication fork. It might create "cross-links" that act like a padlock on the DNA, preventing the helicase from unzipping it. If the cell can’t copy its DNA, it can’t divide. Since cancer cells are the ones dividing the fastest, they get hit the hardest.

Similarly, some antiviral meds are "chain terminators." They look like a normal nucleotide, so the polymerase grabs them and adds them to the growing chain. But these fake nucleotides are "broken"—they don't have the right chemical "hook" for the next nucleotide to attach to. The process stops dead. The virus can't reproduce.

Understanding a picture of dna replication helps you understand why your body responds to medicine the way it does. It’s the fundamental blueprint of life being duplicated, and when that goes wrong, everything goes wrong.

How to Evaluate a Scientific Illustration

Next time you’re looking at an image of this process, ask yourself these questions:

- Does it show the lagging strand looping? If not, it’s skipping the most interesting mechanical part of the process.

- Is there Topoisomerase? If the DNA ahead of the fork looks like a neat spiral, the artist is ignoring physics.

- What about the Single-Strand Binding Proteins (SSBs)? Once DNA is unzipped, it wants to zip back up. SSBs are like little wedges that hold the door open. They should be there, coating the single strands.

- Is the directionality marked? Good science images will label the ends as $5'$ and $3'$. If they don't, it’s just a pretty picture, not a functional map.

DNA replication is the closest thing to a miracle that physics allows. It’s three billion letters being copied by a "machine" that is itself built from those same letters. It's recursive, messy, and insanely fast.

📖 Related: Why the Bose Wave CD System Still Has a Cult Following in 2026

To truly get a handle on this, stop looking for the "perfect" image. Instead, look for the ones that show the complexity—the loops, the "glue" enzymes, and the sheer crowdedness of the cellular environment. Real life isn't a clean diagram; it's a crowded workshop where everything is happening at once.

Actionable Takeaways for Students and Hobbyists

- Search for "Molecular Dynamics Simulations": These are 3D videos based on actual physics. They show the "jiggling" of atoms that static photos miss.

- Check the Source: Images from the Nature journal or Science are going to be more accurate than generic stock photo sites.

- Focus on the "Replisome": Search for this term specifically to see how all the proteins click together into one massive unit.

- Draw it yourself: Honestly, the best way to understand the $5'$ to $3'$ bottleneck is to try and sketch the lagging strand. You'll quickly realize why those Okazaki fragments have to exist.

DNA isn't just a code; it's a physical object that has to be handled, twisted, and copied. The more you look past the simplified picture of dna replication, the more you appreciate the wild engineering that keeps you alive.