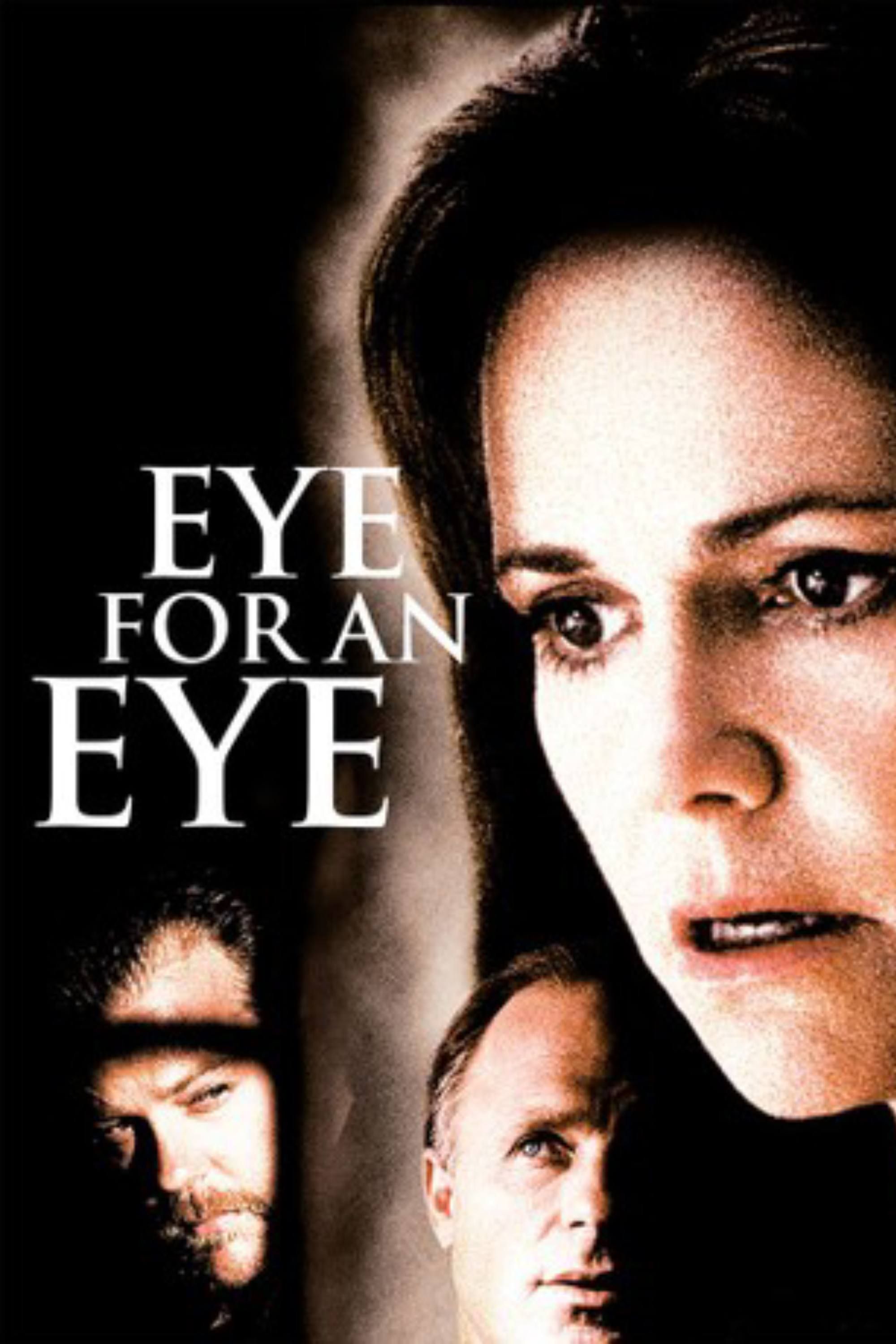

Sally Field screams. It isn’t a cinematic scream, the kind that sounds polished or edited for a trailer. It’s a gut-wrenching, jagged sound of a mother hearing her daughter being murdered over a car phone. That single moment in Eye for an Eye 1996 basically defined a specific era of the psychological thriller.

People don't talk about this movie much anymore. It sort of fell into that mid-90s pocket of "vigilante mom" movies, but if you actually sit down and watch it today, it’s surprisingly mean-spirited and lean. Director John Schlesinger—the same guy who gave us Midnight Cowboy—didn't make a standard action flick. He made a movie about how grief curdles into something unrecognizable. It’s messy. It’s angry. It’s definitely not "feel-good" cinema, even when the "bad guy" gets what’s coming to him.

The Brutal Reality of Eye for an Eye 1996

The plot is straightforward, almost deceptively so. Karen McCann (Field) lives a comfortable, upper-middle-class life until a stranger breaks into her home and kills her eldest daughter. The kicker? The DNA evidence is there, the guy is clearly guilty, but he walks on a technicality. Kiefer Sutherland plays the killer, Robert Doob, and honestly, he has never been more repulsive. He’s a delivery driver who targets women, and Sutherland plays him with this oily, unrepentant arrogance that makes your skin crawl.

Most thrillers of this ilk would spend an hour on the trial. This one doesn't. It moves fast. Once the legal system fails, Karen realizes that the "civilized" world has no interest in her closure. She starts following Doob. She joins a support group that turns out to be a front for people who actually do something about their trauma.

Why the Critics Hated It (and Why They Might Have Been Wrong)

When Eye for an Eye 1996 hit theaters, critics like Roger Ebert absolutely trashed it. They called it "manipulative" and "hateful." And, yeah, they weren't entirely wrong. The film is designed to make you want blood. It uses every trick in the book to make the audience feel the same impotence and rage that Karen feels.

But isn't that the point?

We often demand that our art be "elevated" or "moral," but sometimes a movie just wants to tap into the lizard brain. Schlesinger wasn't trying to make a nuanced documentary on the American judicial system. He was exploring the total breakdown of a person's psyche. Karen isn't a hero in the traditional sense. She becomes a stalker. She lies to her husband (played by Ed Harris, who is perpetually worried in this movie). She turns into a version of the very thing she hates.

The Performance That Anchors the Chaos

Sally Field is the reason this movie works. Without her, it’s a TV-movie-of-the-week. With her, it’s a tragedy. She has this way of looking physically smaller as the movie progresses, her face becoming a mask of exhaustion. You’ve seen her play the "strong mom" before, but this is different. This is a woman who has stopped caring about her own safety because she has already lost the thing that made her feel safe in the world.

Then there’s Kiefer Sutherland. Before he was Jack Bauer saving the world, he was the king of playing absolute scumbags. His Robert Doob is a predator who knows exactly how to work the system. He isn't a criminal mastermind; he's just a guy who knows that if the police mess up the paperwork, he's free to do it again. It’s a cynical view of the world, but for a lot of crime victims, it’s a relatable one.

Technicalities and the 90s Legal System

The movie hinges on the "exclusionary rule." Basically, because of how the evidence was handled or a specific legal loophole, the prosecution's case falls apart. In the mid-90s, there was a massive public fascination (and frustration) with the legal system, largely fueled by the O.J. Simpson trial. People were primed to believe that the system was rigged in favor of the guilty.

Eye for an Eye 1996 tapped directly into that vein of societal anxiety. It asked: If the state can't protect you, and the state won't punish the person who hurt you, do you still owe the state your "civility"?

It’s a dangerous question. The film’s answer is a resounding "No."

Breaking Down the Vigilante Support Group

One of the weirdest and most fascinating parts of the movie is the support group Karen joins. At first, it seems like a standard grief circle. But then she meets people who are tired of talking.

📖 Related: Why The Doctor, the Widow and the Wardrobe is Better Than You Remember

- They don't want "healing" in the therapeutic sense.

- They want a specific type of resolution.

- They provide the training—the weapons handling, the stalking techniques.

This subversion of the "support group" trope is where the movie gets its darkest. It suggests that there is a shadow society of victims who have realized that the only way to get justice is to buy it with their own hands. It’s grim. It’s also probably what made 1996 audiences so uncomfortable. It suggests that under the right circumstances, anyone—even a suburban mom—is capable of premeditated murder.

The Ending That Everyone Remembers

I won't spoil every beat, but the finale isn't a clean shootout. It’s a cat-and-mouse game in a dark apartment. It’s messy and desperate. When the credits roll, you don't feel like "the world is right again." You just feel tired. Karen "wins," but you can see in her eyes that she’s never going back to the person she was in the opening scene.

That’s the nuance that the critics missed. The movie doesn't celebrate her choice; it just shows it as the inevitable result of a broken heart and a broken system.

Legacy of the 1996 Thriller Genre

Where does this fit in the pantheon of 90s cinema? It sits right next to movies like A Time to Kill or Double Jeopardy. These were films obsessed with the idea of "legal" vs. "just."

If you look at the cinematography, it has that specific 90s sheen—lots of browns, deep shadows, and very deliberate pacing. It doesn't rely on jump scares. It relies on the dread of knowing that Doob is out there, somewhere, and he’s looking for his next target.

Honestly, the movie feels more relevant now in the era of true crime podcasts and social media "cancel culture." We are still obsessed with the idea of people "getting away with it." We still have that visceral reaction to injustice.

Actionable Insights for Fans of the Genre

If you’re going to revisit Eye for an Eye 1996, or if you're watching it for the first time, keep a few things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the background characters. The way the police officers (including a young Joe Mantegna) react to Karen is a masterclass in "polite dismissal." It adds an extra layer of frustration to the narrative.

- Compare it to "The Brave One." If you liked the 2007 Jodie Foster movie, you’ll see where a lot of its DNA came from. Both movies deal with the "unreliable" nature of the female vigilante.

- Look for the parallels. Notice how Karen’s relationship with her younger daughter changes. The film subtly shows how her obsession with the dead daughter begins to alienate the living one.

- Check out the source material. The movie is actually based on a novel by Erika Holzer. The book dives even deeper into the legal philosophy of "an eye for an eye" and is worth a read if you want a more intellectual take on the revenge plot.

Ultimately, the movie is a time capsule. It’s a snapshot of a moment when we were collectively terrified of the random stranger and deeply cynical about the institutions meant to keep us safe. It isn't a perfect film, but it is an honest one. It doesn't pretend that revenge is sweet. It just shows that for some people, it feels like the only thing left to do.

If you want to understand the psychological thriller boom of the 90s, you have to watch this. Just don't expect to feel good afterward.

Next Steps for the Movie Buff:

- Rent or stream it on platforms like Vudu or Amazon to see if the tension holds up for you.

- Read Erika Holzer's original novel to see the stark differences in how the "vigilante" group is portrayed versus the film's version.

- Watch John Schlesinger’s Marathon Man right after to see how the director evolved his approach to "ordinary people in extraordinary danger" over twenty years.