You're standing in the middle of a loud, sprawling refinery or maybe a compact HVAC mechanical room. You see those flat steel rings bolted together, holding back hundreds of gallons of pressurized fluid. Those are slip-on flanges. If you’ve ever handled a torch or managed a pipe fit-out, you know that flange slip on welding is basically the bread and butter of the industry. It’s not flashy. It’s not as "heavy-duty" as a weld neck. But it works. Honestly, it’s the most forgiving way to connect pipe sections when you’re dealing with tight spaces or tight budgets.

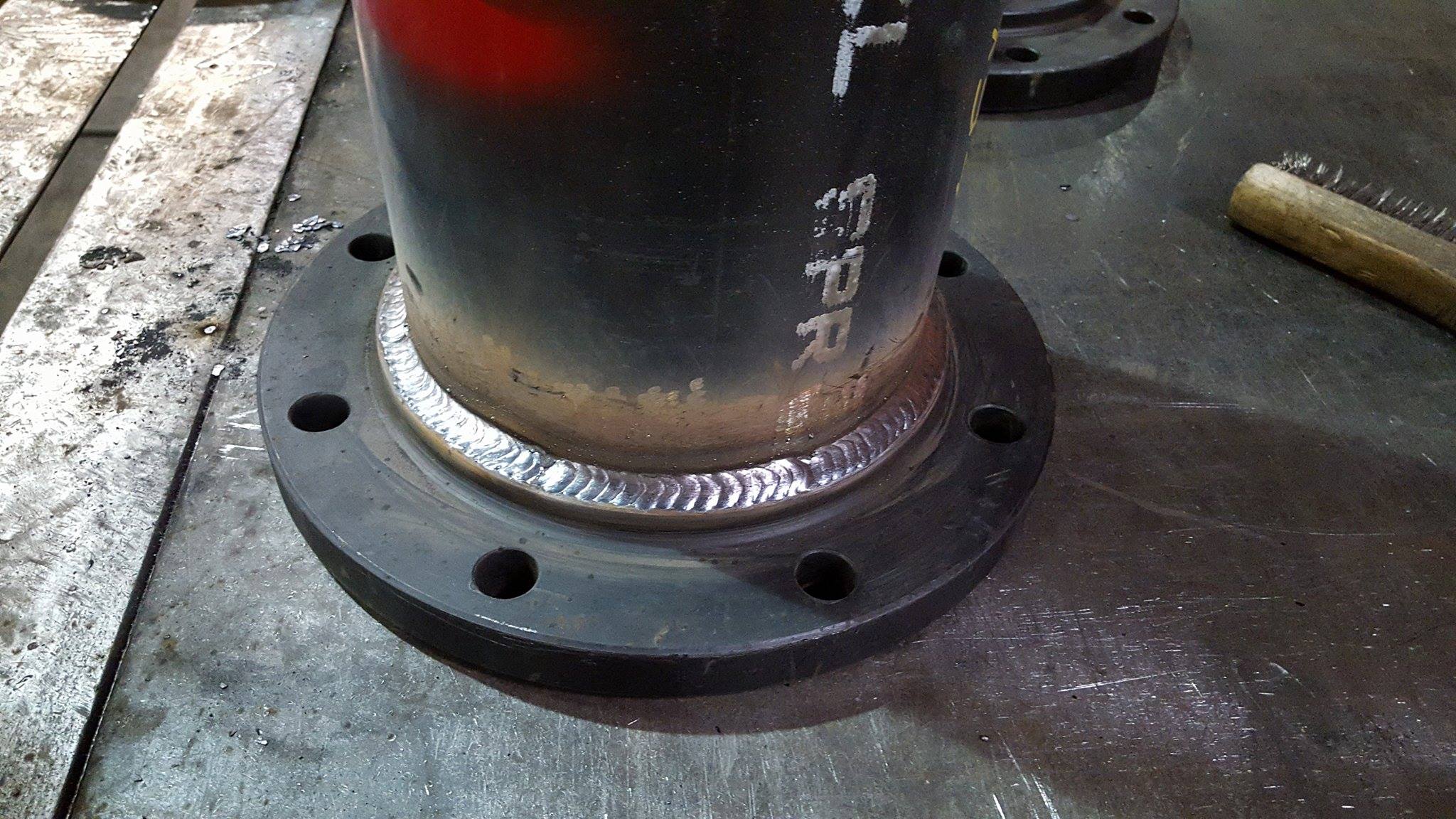

Most people think a flange is just a flange. That's a mistake. The slip-on variety—technically known as a "Hubbed Slip-On"—is unique because the pipe actually slides inside the flange before you start the arc. You aren't doing a butt weld where two edges meet perfectly. You’re doing a double fillet. It’s a different beast entirely.

👉 See also: Solar Power Generator Kit: Why Most People Buy the Wrong One

What Actually Happens During Flange Slip On Welding

When you slide that flange onto the pipe, you aren't just slapping it on and calling it a day. Precision matters. The pipe is typically set back from the face of the flange by about the thickness of the pipe wall plus a little extra—usually around 1/8 of an inch. Why? Because you need room for that internal fillet weld without ruining the gasket seating surface.

You weld the "hub" side—the back part—and then you weld the inside. This double-weld approach is what gives the joint its integrity. If you only weld the back, you’re asking for a leak or a structural failure under vibration. I’ve seen rookies try to skip the internal weld to save time. Don't do that. It creates a stagnant pocket where corrosion can sit and eat your pipe from the inside out.

The heat input during flange slip on welding is something you have to watch. Since the flange is thicker than the pipe, the flange acts like a massive heat sink. You have to aim your arc more toward the flange to get proper penetration without burning through the thinner pipe wall. It’s a balancing act. If you’re using Stick (SMAW), a 6010 for the root and 7018 for the fill and cap is a classic combo, though many shops have moved to MIG (GMAW) for the sheer speed of it.

Why Engineers Often Choose Slip-Ons Over Weld Necks

It usually comes down to two things: cost and clearance.

Weld neck flanges have that long, tapered neck. They require a V-prep on the pipe. They require perfect alignment. Slip-ons? They’re cheaper to buy. They’re easier to align because the pipe can rotate and slide until it’s exactly where you want it. This is a lifesaver when you’re installing a pump and the fixed piping is half an inch off. You just slide the flange, bolt it up, and then weld it in place.

But there is a trade-off.

According to ASME B31.3—the "bible" for process piping—a slip-on flange is generally rated for lower pressure than a weld neck. Under fatigue, a slip-on is only about one-third as strong as a weld neck. That’s a huge difference. If your line is going to be vibrating like crazy or cycling through extreme temperatures every hour, a slip-on might crack at the fillet weld over time. But for cooling water, low-pressure steam, or air lines? It’s perfect.

Common Mistakes That Ruin the Joint

You’d be surprised how often people mess up the "slip" part of the slip-on.

If the pipe is inserted too far, the weld bead on the inside will protrude past the flange face. Now your gasket won't sit flat. You’ll spend the next three hours with a die grinder trying to fix a mistake that took five seconds to make.

- The Gap Issue: Not leaving enough space between the pipe end and the flange face.

- Alignment: Welding the back side first without checking if the flange is "two-holed." Two-holing means ensuring the bolt holes are leveled horizontally so the next piece of equipment actually fits.

- Overheating: Putting too much juice into the weld and warping the flange face. If the face warps, it won't seal. Period.

ASTM A105 is the standard forged carbon steel material you’ll likely be working with. It’s tough. It handles heat well. But if you’re working with stainless steel (like 316L), you have to worry about carbide precipitation. Keep your interpass temperatures low. If that stainless gets too hot for too long, it loses its corrosion resistance, and your "stainless" pipe will start rusting at the weld.

The Realities of Inspection

If you’re working on a high-stakes project, the inspector is going to look at those fillet welds with a magnifying glass. They’ll use a Fillet Weld Gauge. They’re looking for "leg length" and "throat thickness."

For a flange slip on welding job, the leg of the weld should typically be about 1.4 times the thickness of the pipe. If your pipe is 0.250" thick, your weld leg needs to be around 0.35". If it’s undersized, the inspector will reject it. If it’s oversized, you’ve wasted wire and time, and you might have caused unnecessary distortion.

Radiography (X-ray) is tough on slip-ons. Because of the way the pipe overlaps the flange, getting a clear X-ray of the weld is tricky. Most shops prefer Magnetic Particle (MT) or Dye Penetrant (PT) testing for these. It’s faster and usually sufficient for the pressure classes where slip-ons are allowed.

Comparing Material Grades

You can’t just grab any flange. You have to match the chemistry.

- Carbon Steel (A105): The workhorse. Easy to weld, cheap, and everywhere.

- Stainless (A182 F304/316): Used in food, pharma, and chemical. Requires more skill to prevent warping.

- Chrome-Moly: Used in high-temp power plants. These require pre-heating the metal before you even touch it with an electrode. If you don't pre-heat, the weld will literally "tink" and crack as it cools.

Basically, the material dictates the prep.

Does Size Matter?

Actually, it does. On large diameter pipes—say, 24 inches and up—slip-on flanges become massive and heavy. At that scale, the cost savings over a weld neck start to shrink because the amount of welding gas and wire needed for those huge fillet welds adds up. In the smaller sizes (2" to 8"), the slip-on is king.

Actionable Steps for a Better Weld

If you’re heading out to the shop to start a flange slip on welding task, follow this flow. It’ll save your reputation and your back.

Clean the Pipe and Flange

Don't weld over mill scale or rust. Use a flap disc and get it down to shiny metal. Porosity is a nightmare, and it usually happens because someone was too lazy to clean the oil off the pipe.

The "Two-Hole" Alignment

Slide the flange on. Put a level across two of the bolt holes. Make sure it's dead level before you tack it. If you're slightly off, the guy installing the valves later will hate you.

Set Your Set-Back

Measure your pipe insertion. Leave that 1/8" (3mm) gap from the face. Use a small spacer or a specialized "gap-o-let" tool if you have one.

Tack Weld Strategically

Tack at 12, 6, 3, and 9 o'clock. Check the squareness of the flange to the pipe after the first two tacks. Steel moves when it gets hot. You have to fight that movement.

Weld the Hub First

Run your bead around the back hub. This anchors the flange. Then, move to the inside. Keep your angle sharp to ensure you're getting into the root of the joint.

✨ Don't miss: USB Type A to Type C Adapter: Why Your Old Cables Aren't Ready for the Trash Just Yet

Final Inspection

Let it cool naturally. Don't throw water on it to speed things up—that can cause "quenching" cracks. Once it’s cool, wipe it down and check for any undercut or slag inclusions.

If you follow these steps, your flange slip on welding will pass any QC check. It’s about the fundamentals. Keep your arc tight, your metal clean, and your measurements precise. This isn't just about sticking two pieces of metal together; it's about building a system that won't fail when the pressure's on.