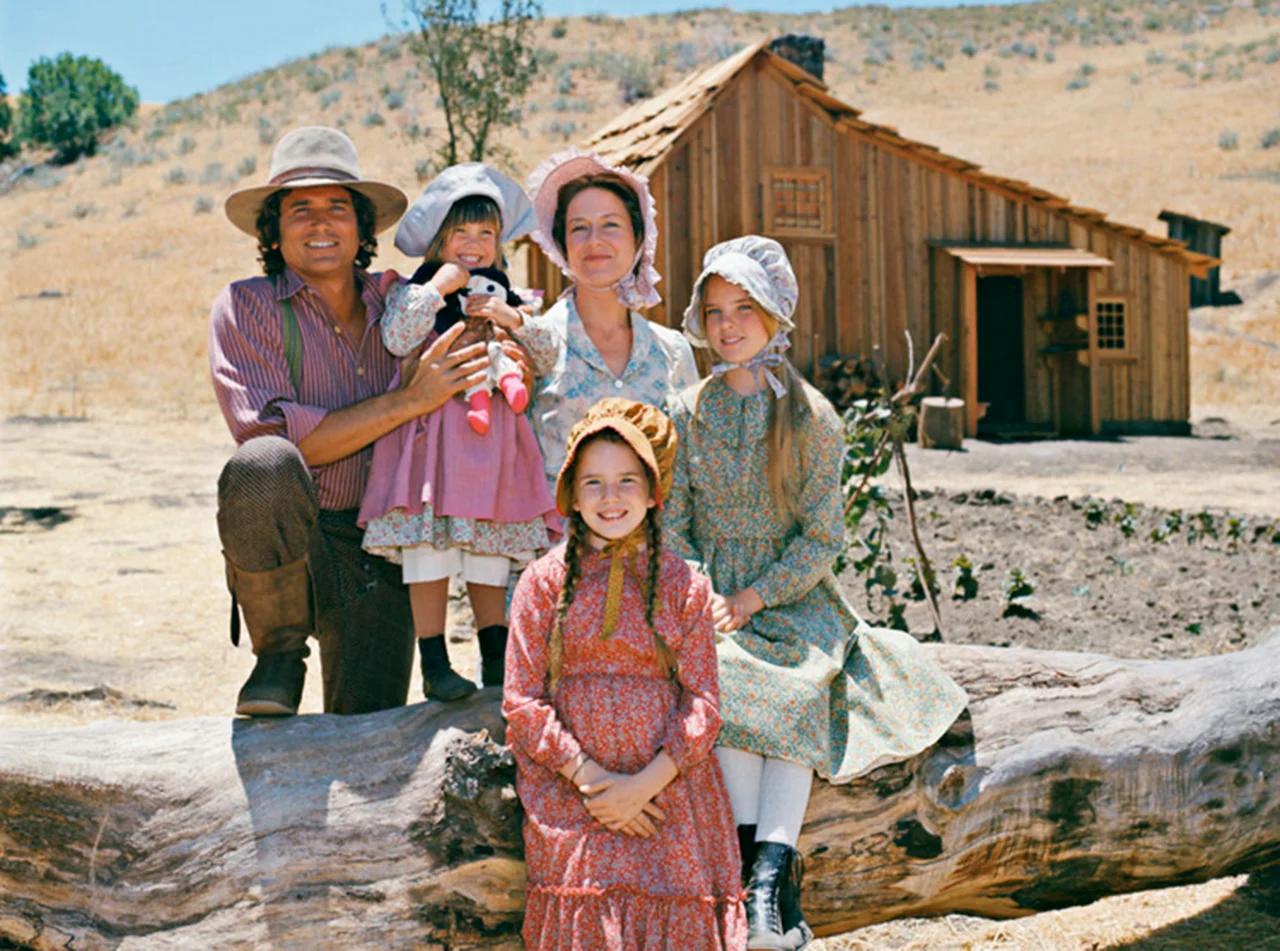

By the time the cameras started rolling for Little House on the Prairie Season Four in 1977, the show wasn't just a hit; it was a cultural phenomenon. But something shifted that year. If you grew up watching Michael Landon’s Charles Ingalls toss his daughters in the air, you probably remember the feeling of those early seasons—the cozy warmth of the little house in the Big Woods or the wide-open spaces of Walnut Grove. Season four, however, decided to grow up. It got grittier. It got heavier. Honestly, it took some of the biggest narrative risks in the history of 1970s family television.

People usually point to the later years when talking about the show’s "tragedy porn" reputation, but the seeds were planted right here. We saw the departure of Mr. Edwards—Victor French left to star in Carter Country—which left a massive, grizzly-sized hole in the cast. We saw the Ingalls family face financial ruin that actually felt permanent for once. And, of course, we reached the emotional precipice of the series: Mary Ingalls losing her sight. It’s a lot to process, even decades later.

The Turning Point for Mary Ingalls

Let’s talk about "I'll Be Waving as You Drive Away." This wasn't just another episode. It was a two-part event that fundamentally altered the DNA of the show. Up until Little House on the Prairie Season Four, Mary was the perfect one. She was the scholar, the rule-follower, the one destined for the easy path. When Michael Landon and the writers decided to follow the historical reality of Mary’s life—though they attributed it to scarlet fever rather than the viral meningoencephalitis historians now suspect—it broke the audience's heart.

✨ Don't miss: Set Fire to the Rain Lyrics: Why Adele’s Impossible Metaphor Still Hits So Hard

Melissa Sue Anderson’s performance was staggering. She didn't play it for cheap pity. She played the anger. You see her throwing things, screaming at Charles, and retreating into a dark shell of herself. It was raw. Watching it today, you realize how much the show relied on her ability to transition from a sighted girl to someone navigating a world that had suddenly become terrifyingly small. Then came Adam Kendall. Linwood Boomer joined the cast as the teacher at the school for the blind in Iowa, and suddenly, the show wasn't just about a farm; it was about disability, resilience, and the terrifying cost of independence in the 1880s.

Michael Landon’s Vision and the Walnut Grove Exodus

Michael Landon was a bit of a control freak, but in the best way possible for a showrunner. He knew that for Little House on the Prairie Season Four to stay relevant, the stakes had to stay high. He wasn't afraid to make the Ingalls family suffer, which sounds cruel, but it’s why the show still resonates. In the season finale, "I'll Be Waving as You Drive Away," the family actually has to leave Walnut Grove.

Think about that.

They spent four years building this town, and then, because of a failing economy and poor crops, they just... leave. They pack the wagon and head for Winoka. It’s a gut-punch. It reflected the real-life anxieties of the 1970s recession, making the 19th-century struggles feel incredibly contemporary for the viewers at home.

The season also experimented with some weirder, more standalone stories. Remember "The Wolves"? It was essentially a horror movie disguised as a family drama. Laura and Andy Garvey are trapped in a barn with a pack of aggressive timber wolves while their parents are away. It’s tense, it’s violent, and it’s a far cry from the "going to the mercantile to buy peppermint sticks" vibes of season one. It showed that Landon was willing to play with genre, pushing the boundaries of what a "family show" could actually be.

The New Faces and Missing Friends

Losing Victor French was a blow. Isaiah Edwards was the grit to Charles’s polish. To fill that void, the show introduced the Garvey family. Merlin Olsen, the former NFL defensive tackle, stepped in as Jonathan Garvey. He was massive, kind, and had a believable chemistry with Landon. The dynamic between Jonathan and Alice Garvey (played by Hersha Parady) offered a different look at marriage than the near-perfect union of Charles and Caroline. They fought. They had real, prickly disagreements about money and parenting.

- Jonathan Garvey: The new emotional anchor and Charles's right-hand man.

- Andy Garvey: A best friend for Laura, bridging the gap left by older kids growing up.

- Nellie Oleson: Still the queen of mean, but starting to show the tiny, microscopic cracks of humanity that would later define her character arc.

- Kezia: The eccentric hermit played by Hermione Baddeley, who brought a touch of whimsical Victorian Gothic to the prairie.

Basically, season four was about expansion. We weren't just in the little house anymore. We were in the woods with hermits, in the dark with Mary, and eventually, in the crowded, dirty streets of a big city.

Why Season Four Hits Different Today

If you rewatch it now, you'll notice the pacing is... let's say "deliberate." It's slow. It lets the silence sit. In the episode "The Handyman," there’s this incredible tension between Caroline and a guest worker (played by a young Gil Gerard) while Charles is away. It flirts with the idea of infidelity in a way that’s so subtle and sophisticated it probably flew over most kids' heads.

💡 You might also like: Why the Bloody Elevator in The Shining Still Terrifies Us 45 Years Later

The show was tackling "The Myopia of the Patriarch." Charles often made decisions for the whole family that were, frankly, reckless. Season four starts to call him out on that. Caroline’s strength becomes more visible. She’s not just the woman in the kitchen; she’s the one holding the emotional floor together while Mary’s world goes black and Charles's crops wither in the heat.

Technically, the cinematography in Little House on the Prairie Season Four also took a leap. The use of golden hour lighting and those sweeping shots of the Simi Valley (doubling for Minnesota) became more iconic. They had the budget, and they used it to create an Americana mythos that looked like a living painting.

The Reality Check: History vs. Hollywood

We have to be honest: the show played fast and loose with Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books by this point. The real Mary Ingalls went to the Iowa Braille and Sight Saving School in 1881, and while the show gets the emotional beat right, the timeline is compressed for TV. But that’s okay. The show was never a documentary. It was an exploration of 19th-century values through a 20th-century lens.

Season four is the pivot point where the series stopped being "the book on screen" and became its own entity. It’s the season where Laura starts to transition from a "half-pint" child into the young woman who would eventually lead the show. You see her grappling with jealousy, grief, and the looming shadow of adulthood. It’s heavy stuff for a Sunday night.

How to Experience Season Four in the Modern Era

If you’re planning a marathon, don’t just binge it in the background. Pay attention to the score by David Rose. The way he uses the fiddle and the swelling strings during the "Mary goes blind" arc is a masterclass in television scoring. It’s manipulative, sure, but it works every single time.

💡 You might also like: Silicon Valley Russ Hanneman: What Most People Get Wrong About the 3 Comma King

Essential Watch List for Season Four:

- Castoffs: A beautiful, quiet look at aging and loneliness.

- The Wolves: For when you want a little 19th-century adrenaline.

- I'll Be Waving as You Drive Away (Parts 1 & 2): Bring a box of tissues. Seriously.

- The High Cost of Being Right: A brutal look at how pride can destroy a family's finances.

To get the most out of these episodes, compare them to the actual memoirs Pioneer Girl. You'll find that while the show added the drama, the underlying fear of "one bad harvest and we lose everything" was 100% authentic.

Check the remastering on modern streaming platforms; the colors are vibrant enough to make those prairie landscapes feel like they're right outside your window. The restoration work done for the 40th anniversary (and beyond) has kept the film grain intact while cleaning up the dust, making it look better than it ever did on a 1970s tube TV.

Once you finish the season, look into the history of the Iowa School for the Blind. It’s a fascinating deep dive that adds a layer of respect to what Melissa Sue Anderson and Linwood Boomer portrayed on screen. They weren't just playing characters; they were representing a community that rarely saw itself on television in such a nuanced way back then.

Keep an eye out for the subtle costume changes too. As the family moves toward the city in the finale, the rough homespun fabrics give way to slightly more structured, urban styles. It’s a visual cue that the "little house" era is ending and a more complicated, "urban prairie" era is beginning. This season didn't just tell a story; it closed a chapter of American childhood and forced its characters—and its audience—to grow up.