You think you’re being unpredictable. You’re sitting there, maybe trying to settle a bet or pick a winner for a giveaway, and you decide to pull a 1 100 random number out of thin air. You settle on 73. Or maybe 42. You feel like you’ve bypassed logic and tapped into the chaotic ether of pure chance.

Actually, you haven't. Honestly, you're probably just following a predictable psychological pattern that researchers have been documenting for decades.

✨ Don't miss: Finding People Who Look Like Me: The Tech and Psychology of Your Digital Doppelgänger

Humans are notoriously terrible at being random. If I ask a room of a hundred people to pick a number between 1 and 100, a disproportionate amount of them will flock to "7" or "17" or "73." We avoid the edges. We avoid 1. We avoid 100. We avoid multiples of five because they feel too "structured." We’re basically walking algorithms, and not very good ones at that.

The Math Behind the 1 100 Random Number Range

True randomness is harder to find than most people realize. In the world of computing, we talk about Pseudorandom Number Generators (PRNGs). These aren't actually random. They use a "seed"—usually a timestamp down to the millisecond—and run it through a complex mathematical formula to spit out a result.

If you know the seed and you know the algorithm, you can predict the next number. Every single time. This is why high-stakes security systems or professional gambling platforms don't rely on basic PRNGs. They use True Random Number Generators (TRNGs). These bad boys pull entropy from the physical world. We're talking about atmospheric noise, radioactive decay, or even the microscopic fluctuations in thermal energy.

When you use a digital tool to generate a 1 100 random number, you’re likely using a Mersenne Twister. It's the industry standard for most programming languages like Python or Ruby. It has a massive period of $2^{19937}-1$, which basically means it won't repeat its sequence for longer than the lifespan of the universe. For your office pool or your Dungeons & Dragons session, that’s more than enough randomness.

Why We Can't Just "Think" of a Random Number

Stanford University researchers and cognitive scientists have spent a lot of time watching people fail at being random. There’s this thing called the "availability heuristic." Essentially, your brain grabs whatever is closest or most "meaningful."

📖 Related: Whirlpool Duet Dryer Control Board: Why Your Dryer is Acting Weird (and How to Fix It)

Numbers like 7 are viewed as "lucky" in Western cultures. Numbers ending in 3 or 7 feel "more random" to us than even numbers like 20 or 50. If you ask someone for a 1 100 random number, and they say "37," they aren't being creative. They are subconsciously reacting to the fact that 37 is a prime number that doesn't "feel" like it belongs to a pattern.

It's a trap.

True randomness is clumpy. If you flip a coin 100 times, you're statistically likely to see a streak of six or seven heads in a row at some point. But if you ask a human to write down a random sequence of 100 coin flips, they will almost never include a long streak. They think, "Well, I've had three heads, so the next one must be tails to keep it random." That’s the Gambler’s Fallacy. Randomness doesn't have a memory. The number 42 doesn't "know" it was picked last time.

Practical Uses for the 1 to 100 Range

Why specifically 1 to 100? It’s the perfect scale for human comprehension. We think in percentages.

- Gaming and RPGs: While the D20 (1-20) is the king of Dungeons & Dragons, many systems like Call of Cthulhu use "percentile dice." You roll two ten-sided dice to get a 1 100 random number to determine if your character successfully picks a lock or stays sane while looking at a tentacle monster.

- A/B Testing: Marketers use random number generation to split website traffic. If a user is assigned a number from 1-50, they see Version A. If they get 51-100, they see Version B.

- Giveaways: It’s the easiest way to keep things fair. If you have 87 entries, you just generate one number. No bias. No "picking the person with the cutest profile picture."

The Security Risk of "Bad" Randomness

In 2008, a massive vulnerability was found in Debian Linux's OpenSSL implementation. A developer, trying to clean up some code, accidentally removed the lines that added entropy to the random number generator. The result? The system only had 32,767 possible "random" outcomes.

In the world of cryptography, that's like leaving your front door wide open. Hackers could predict the "random" keys and break into encrypted communications.

When you're just picking a 1 100 random number for a board game, the stakes are low. When you're generating a cryptographic key that protects your bank account, the randomness needs to be absolute. This is why modern hardware often includes dedicated chips just to generate "noise" for the CPU to use as a seed.

💡 You might also like: Family Sex Videos and Digital Safety: What the Research Actually Shows About Privacy and Risks

How to Get a Truly Random Result

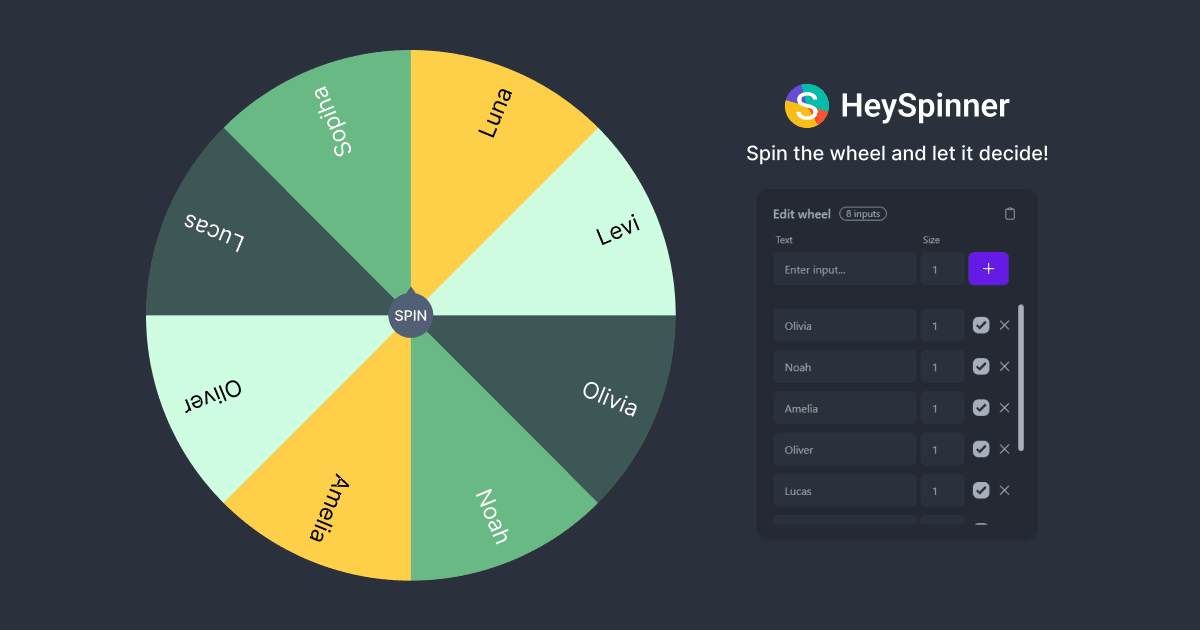

If you actually need a 1 100 random number and you don't trust your own biased brain, you have options.

- Physical Dice: Buy a "Zocchihedron." It's a 100-sided die. It looks like a golf ball and rolls for about three minutes before stopping, but it’s a physical manifestation of gravity and friction.

- Atmospheric Noise: Sites like RANDOM.ORG use radio receivers to pick up atmospheric noise. They claim this is "true" randomness because it’s based on the chaotic nature of the weather and the planet.

- Google's Built-in Tool: Just type "random number generator" into Google. It uses a PRNG that is perfectly fine for 99% of human needs.

Making the Choice Count

Stop trying to think of a "good" number. There is no such thing. If you're using this for a decision—like picking which restaurant to go to or who has to take out the trash—the power isn't in the number itself. The power is in the commitment to the result.

Most people use a 1 100 random number generator to offload "decision fatigue." We make about 35,000 decisions a day. Using a bit of math to decide if you’re eating tacos or pizza isn’t lazy; it’s an efficient use of cognitive resources.

Actionable Steps for Better Randomness

- Don't trust your gut: If fairness matters, never pick the number yourself. Use a digital tool or physical dice.

- Check your seeds: If you are a developer, never use a static seed (like

seed(1)) in production. Your "random" numbers will be the same every time the program restarts. - Embrace the clumps: If you get the number 12 three times in a row, don't assume the machine is broken. In a truly random 1-100 set, weird clusters are actually a sign that the system is working correctly.

- Use the "Coin Flip" trick: If you use a generator to decide between two things and you feel disappointed by the result, you actually already knew what you wanted. Go with the other choice.

Randomness is a tool. Whether you're coding a game, securing a server, or just trying to pick a winner for a raffle, understanding the gap between "human random" and "math random" changes how you see the world.

Next time you need a 1 100 random number, remember: your brain wants to pick 73. Don't let it.