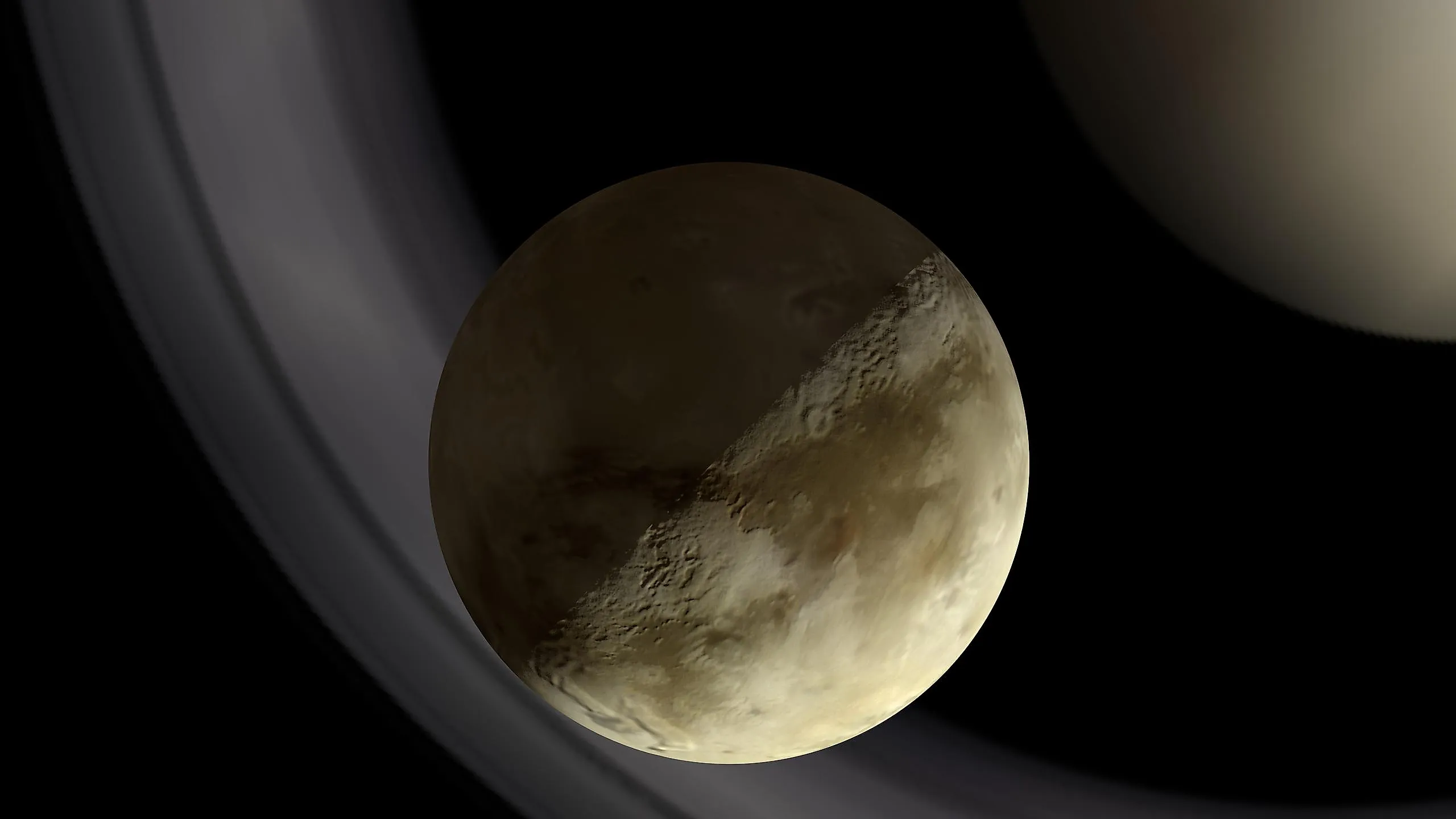

If you glanced at a few raw pictures of Saturn's moon Titan without context, you’d be forgiven for thinking someone just took a grainy, sepia-toned photo of the Namib Desert or a foggy morning in the Scottish Highlands. It's eerie. Really eerie. We are talking about a world nearly a billion miles away from the Sun, where the temperature sits at a bone-chilling -290 degrees Fahrenheit, yet it has riverbeds. It has lakes. It has rolling sand dunes.

But here’s the kicker: it’s not water.

On Titan, the "rocks" are made of water ice frozen so hard they act like granite. The "rain" and the liquid filling those vast northern lakes? That’s liquid methane and ethane. When we look at images sent back by the Cassini spacecraft or the Huygens probe, we aren't just looking at another dead moon. We’re looking at a funhouse-mirror version of Earth. It's a world where the chemistry is totally alien, but the geology is hauntingly familiar.

The Day We Landed: The Huygens Perspective

January 14, 2005. That was the day the game changed. Before the ESA’s Huygens probe detached from Cassini and took its plunge through Titan’s thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere, we basically knew nothing about the surface. Titan is shrouded in a global orange haze—a photochemical smog created when sunlight breaks down methane. You can’t see through it with normal cameras.

Huygens drifted down for two and a half hours. The pictures it took during that descent are some of the most important images in the history of space exploration. At first, it just looked like shadows. Then, drainage channels appeared. They looked exactly like river deltas on Earth.

👉 See also: How Many Seconds in 1 Minute? Why the Math Actually Gets Complicated

When it finally touched down—with a literal "splat," indicating the ground had the consistency of wet sand or crème brûlée—it snapped a photo of its surroundings. You’ve probably seen it. It shows a flat plain strewn with rounded cobbles. On Earth, rocks get rounded by tumbling in riverbeds. On Titan, those "rocks" are chunks of water ice, smoothed out by liquid hydrocarbons flowing across the landscape.

It’s the only time we’ve ever seen the surface of a moon in the outer solar system from the ground. It feels lonely. It feels cold. But it also looks like somewhere you could actually walk, assuming you had a very good heater and an oxygen tank.

Piercing the Haze: How We See Titan from Orbit

Because the atmosphere is so thick, taking pictures of Saturn's moon Titan from the Cassini orbiter required some technological trickery. NASA couldn't just use a standard "point and shoot" camera for everything. Instead, they used Radar and the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS).

Radar is how we found the lakes.

By bouncing radio waves off the surface, Cassini revealed areas that were incredibly smooth. In radar imagery, smooth surfaces appear black. These black patches, concentrated mostly in the north polar region, are massive bodies of liquid. Kraken Mare, the largest, is bigger than the Caspian Sea on Earth.

Not Just Liquid, But Weather

The VIMS instrument allowed us to peer through "windows" in the atmosphere at specific infrared wavelengths. This is how we mapped the Great Sand Seas. If you look at images of Titan’s equatorial regions, you see these massive, dark streaks. They’re dunes.

They aren't made of silicate sand like the Sahara. Instead, they’re composed of "hydrocarbon snow"—organic particles that drift down from the atmosphere and get whipped into 300-foot-tall dunes by Titan’s tidal winds. Think about that. The "sand" is basically solid bits of plastic-like material.

Dr. Elizabeth Turtle, a lead scientist on the Dragonfly mission (more on that later), has noted that Titan’s weather cycles are incredibly slow. It might only rain in a specific spot once every few decades, but when it does, it's a deluge. We’ve actually seen "brightening" events in images where the surface changes color after a storm, suggesting the ground got soaked by methane rain.

The Mystery of the "Magic Islands"

One of the weirdest things ever captured in pictures of Saturn's moon Titan happened in Ligeia Mare. Over several years, Cassini took images of the same spot in the lake. In some frames, a bright "island" appeared. In the next, it was gone.

Scientists called them "Magic Islands."

For a while, there was a lot of debate. Was it waves? Was it floating solids? Recent research suggests these might actually be nitrogen bubbles fizzing up from the depths of the methane lakes, or perhaps "honeycombed" icebergs of organic solids that stay afloat for a while before sinking. It’s a dynamic, changing world. It isn't a static rock like our Moon. It breathes. It shifts.

Why These Images Are Hard to Process

When you look at a gallery of Titan photos, you'll notice they often look very different. Some are neon green and blue. Some are muddy orange.

👉 See also: How Do You Go to the Bathroom in Space? The Messy Reality Astronauts Face

- Natural Color: This is what your eyes would see. It’s mostly a featureless orange ball because of the smog.

- False Color Infrared: Scientists assign colors (like blue for water ice and brown for organics) to different wavelengths so we can actually tell what we're looking at.

- Radar Maps: These are often rendered in shades of gold or grey to show texture and elevation.

It's easy to get confused. The "blue" you see in many VIMS images isn't water; it's usually just a representation of the ice-rich bedrock. The "dark" areas are where the organic "soot" has collected.

The Future: Dragonfly and the Quest for High-Res

The images we have are great, but they’re old. Cassini ended its mission in 2017 by diving into Saturn's atmosphere. We haven't had a new "close-up" of Titan in years.

That changes with Dragonfly.

NASA is sending a rotorcraft—basically a car-sized drone—to Titan. It’s scheduled to arrive in the mid-2030s. Because Titan’s atmosphere is four times denser than Earth’s and the gravity is much lower, flying is easy. If you strapped wings to your arms, you could fly on Titan.

Dragonfly will take high-definition, color pictures of Saturn's moon Titan as it hops from one site to another. We’re going to see the "Selk Crater" in a resolution that will make the Cassini images look like 1920s silent films. We are looking for "prebiotic" chemistry. Basically, we want to know if the ingredients for life are sitting in those organic dunes, just waiting for a splash of liquid water (from a meteor impact, for example) to kickstart something interesting.

What You Can Actually Do With This Information

If you're a space nerd or just someone who likes looking at weird worlds, don't just settle for the low-res thumbnails on Google Images.

First, head over to the PDS (Planetary Data System) Imaging Node or the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Photojournal. You can search specifically for "Titan" and "Cassini" to find the raw datasets.

If you want to see what the surface feels like, look for the "Huygens Landing Movie." It’s a stitched-together sequence of the actual descent. It’s grainy, but it’s real footage of a landing on a moon 800 million miles away.

Actionable Insights for Amateur Observers:

- Check the Infrared: Use the JWST (James Webb Space Telescope) public data releases. Webb has been taking new images of Titan, and while they aren't as close as Cassini, they show cloud movements and seasonal changes in real-time.

- Monitor the Dragonfly Mission: Follow the JHU Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) updates. They are the ones building the drone.

- Contextualize the Scale: When you see a "river" on Titan, remember that the liquid is roughly the density of water but much colder. The "pebbles" in those rivers are water ice. Understanding the material science makes the pictures much more impactful.

Titan is arguably the most "Earth-like" place in the solar system, but it's built out of all the wrong materials. We have the pictures to prove it's a world of mountains, lakes, and storms. We just have to get used to the fact that on Titan, water is the rock and gas is the rain.