You’re 35,000 feet over the Rockies when the coffee starts dancing in your cup. It’s a tiny tremor at first, then a sharp jolt that sends a stray napkin fluttering into the aisle. You look at the flight attendant, who seems perfectly calm, and you wonder how they knew to sit down thirty seconds before the bumps actually started. It’s not magic. It isn't just "weather radar" either.

The secret is a constant, invisible chatter of pilot reports of turbulence, known in the industry as PIREPs.

Honestly, most passengers think the cockpit has a giant "turbulence map" that shows every ripple in the air. They don't. Radars are great for spotting moisture—think thunderstorms and heavy rain—but they are notoriously blind to Clear Air Turbulence (CAT). To find the bumps in perfectly clear skies, pilots rely on the person who just flew through them. It’s a relay race of data. One captain hits a rough patch, keys the mic, and tells Air Traffic Control (ATC) exactly where, when, and how bad it was.

The Raw Reality of Pilot Reports of Turbulence

A PIREP is basically a verbal status update. When a pilot encounters "ride conditions" that aren't smooth, they transmit a report. ATC then broadcasts this to every other aircraft in the sector. If you’ve ever wondered why your pilot suddenly announces a climb to 38,000 feet "to find some smoother air," it’s almost certainly because someone five minutes ahead of you just filed a report saying 34,000 feet was a washboard.

It’s a manual system in a digital world.

Think about that for a second. In an era of AI and satellite links, we still rely on one human being describing their physical sensations to another human being. A PIREP usually includes the location, time, altitude, aircraft type, and the intensity of the turbulence.

Intensity is where it gets subjective. What feels like "Moderate" turbulence to a seasoned captain in a massive Boeing 777 might feel like "Severe" to a rookie in a small Cessna. There’s a constant mental calibration happening. Pilots have to account for the "heavies" versus the "lights." If a Delta pilot in an A350 reports "Light Chop," everyone in a smaller regional jet nearby knows they’re about to get hammered.

Decoding the Turbulence Language

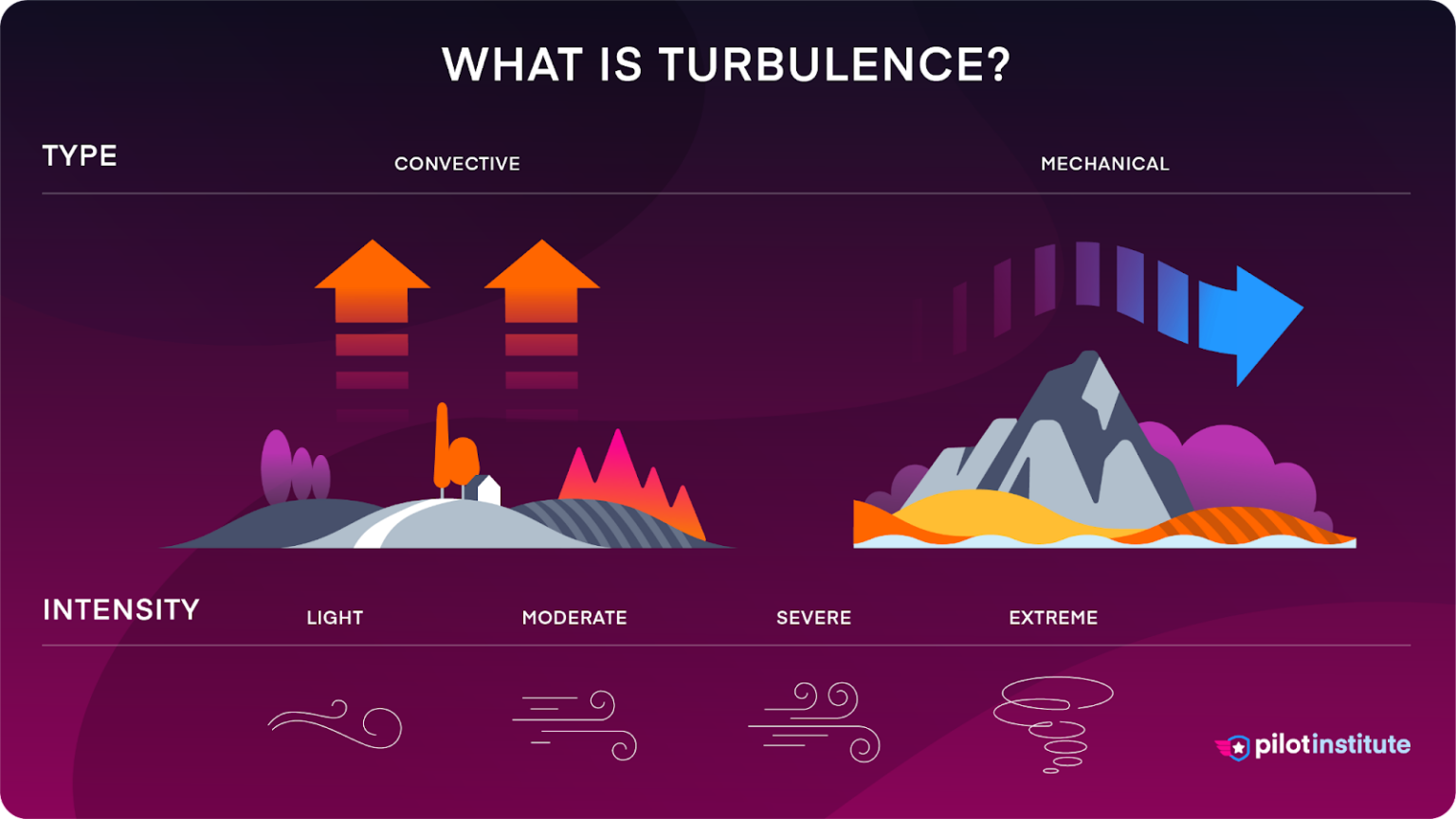

When you hear pilots talking, they use a specific scale. It’s not just "bumpy" or "scary."

Light Turbulence is just a slight, rhythmic bumpiness. You can still walk. Your drink might ripple. Moderate Turbulence is the point where the seatbelt sign definitely comes on. You’ll feel definite strains against your belt. Objects might move around. If a pilot reports "Moderate," the flight attendants are usually told to take their seats immediately.

Then there’s Severe. This is rare. We’re talking about the aircraft being momentarily out of control. It’s violent. Occupants are thrown against seatbelts.

"Extreme" is the one nobody wants to talk about. That’s structural damage territory. Fortunately, thanks to the frequency of pilot reports of turbulence, most flights are steered far away from anything approaching "Severe" before they even get close.

Why the System Is Kind of Broken (But Still Works)

Here is the thing: the PIREP system is old. It's clunky.

A pilot has to find a gap in radio transmissions to report the bumps. Then, the controller has to type that report into a legacy computer system. Sometimes there’s a delay. Sometimes the controller is too busy handling arrivals into O'Hare to worry about a "Light Chop" report from a guy at 30,000 feet. This "human in the loop" requirement means that by the time a report reaches a dispatcher or another cockpit, the pocket of rough air might have moved or dissipated.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) data has highlighted this for years. They’ve noted that the lack of real-time, automated turbulence reporting is a leading cause of weather-related accidents.

The Rise of the EDR

Lately, technology is trying to catch up. Some newer planes use Eddy Dissipation Rate (EDR). This is basically an automated PIREP. Instead of a pilot saying "it feels bumpy," the plane’s sensors measure exactly how much the air is churning and send that data via satellite.

Delta Air Lines has been a leader here. They use an app that gives pilots a high-resolution "heat map" of turbulence. It combines traditional pilot reports of turbulence with atmospheric models and automated sensor data. It’s much more precise than a verbal "hey, it’s bumpy over Kansas."

But even with EDR, the verbal report remains king. Why? Because a sensor can't tell you if the clouds look "mean" or if there’s a massive mountain wave forming that hasn't been picked up by the algorithms yet. Human intuition still matters.

Mountains, Jet Streams, and the Invisible Threat

Why is turbulence so hard to predict anyway?

Most of the time, pilots are looking for three things:

- Convective Activity: Thunderstorms. These are easy to see on radar.

- Mountain Waves: Air flowing over mountains like water over a rock in a stream. This creates ripples that can reach way up into the stratosphere.

- Jet Streams: High-altitude "rivers" of fast-moving air. The edges of these streams, where fast air meets slow air, are where the "Clear Air Turbulence" lives.

The "Clear Air" stuff is the real villain. It’s invisible. You can’t see it on radar because there’s no moisture for the radio waves to bounce off of. This is why pilot reports of turbulence are the only way to "see" it. If a United flight at FL360 (36,000 feet) reports "Moderate CAT," every dispatcher in the country sees that red dot on their screen and starts moving their planes.

Climate change is making this worse. Research from Paul Williams at the University of Reading suggests that Clear Air Turbulence is becoming more frequent and more intense as the jet stream becomes more unstable. We are seeing more reports of "extreme" encounters—like the tragic Singapore Airlines flight in 2024 or the Hawaiian Airlines incident in 2022.

What This Means for Your Next Flight

So, how do you actually use this info? You can’t exactly call the cockpit and ask for the latest PIREPs.

But you can be smart.

First, understand that a "bumpy ride" doesn't mean the plane is falling apart. Wings are designed to flex like bird wings. A Boeing 787 wing can flex upwards of 25 feet before it even thinks about breaking. The danger isn't the plane breaking; it's you hitting the ceiling because you didn't have your belt on.

Second, listen to the tone of the pilot. If they sound casual about the "pilot reports of turbulence" ahead, it's because they've already mapped out a plan. They aren't guessing. They are navigating a 3D maze of air based on the reports of those who went before them.

Actionable Tips for Navigating the Bumps

Don't just sit there and worry. Use the same logic pilots use.

- Keep the belt buckled. Always. Even if the sign is off. Most injuries occur during "Light" turbulence when people are standing in the aisle or have their belts unfastened.

- Sit over the wing. If you’re prone to motion sickness, the center of gravity is the most stable part of the aircraft. The tail is like the end of a whip—it moves the most.

- Watch the flight attendants. They are the ultimate "turbulence barometers." If they are still serving ginger ale, you’re fine. If they’re sprinting to their jumpseats, tighten your belt.

- Use the Apps. Check sites like TurbulenceForecast.com or apps like SkyGuru before you fly. These tools aggregate pilot reports of turbulence and weather models to give you a "heads up" on what your route looks like.

- Fly Early. Convective turbulence (from heat) usually builds throughout the day. Morning flights are statistically smoother because the ground hasn't had time to heat up and create those rising "thermals" that cause bumps.

The Future of the Report

We are moving toward a world where every plane is a weather station. Within the next decade, the manual "voice" PIREP will likely become a secondary backup. Companies like IATA are pushing their "Turbulence Aware" platform, which pools real-time automated data from thousands of flights across different airlines.

Until then, we rely on the fraternity of the sky.

That crackly voice on the radio saying, "Center, Cactus 1542, we’re catching some pretty good chops at three-four-zero, requesting three-six-zero," is the most important safety tool in the sky. It’s a human warning system that keeps millions of people safe every year.

Next time you feel that jolt, just remember: your pilot already knows it’s there. They’ve heard the reports. They’ve seen the data. And they are already looking for the "smooth" that someone else just found five minutes ago.

✨ Don't miss: Hertz Car Rental Orlando Airport: What Most People Get Wrong About Picking Up Your Keys at MCO

Next Steps for Your Travel Prep:

- Check the "Surface Analysis Chart" or a turbulence map 2 hours before your flight to see where the jet stream is sitting.

- Download a "G-Force" app if you are a nervous flier; seeing that the "drops" are actually only 0.2Gs can help rationalize the fear.

- Choose a seat in the front third of the cabin if you want to minimize the physical sensation of the tail-wagging turbulence.