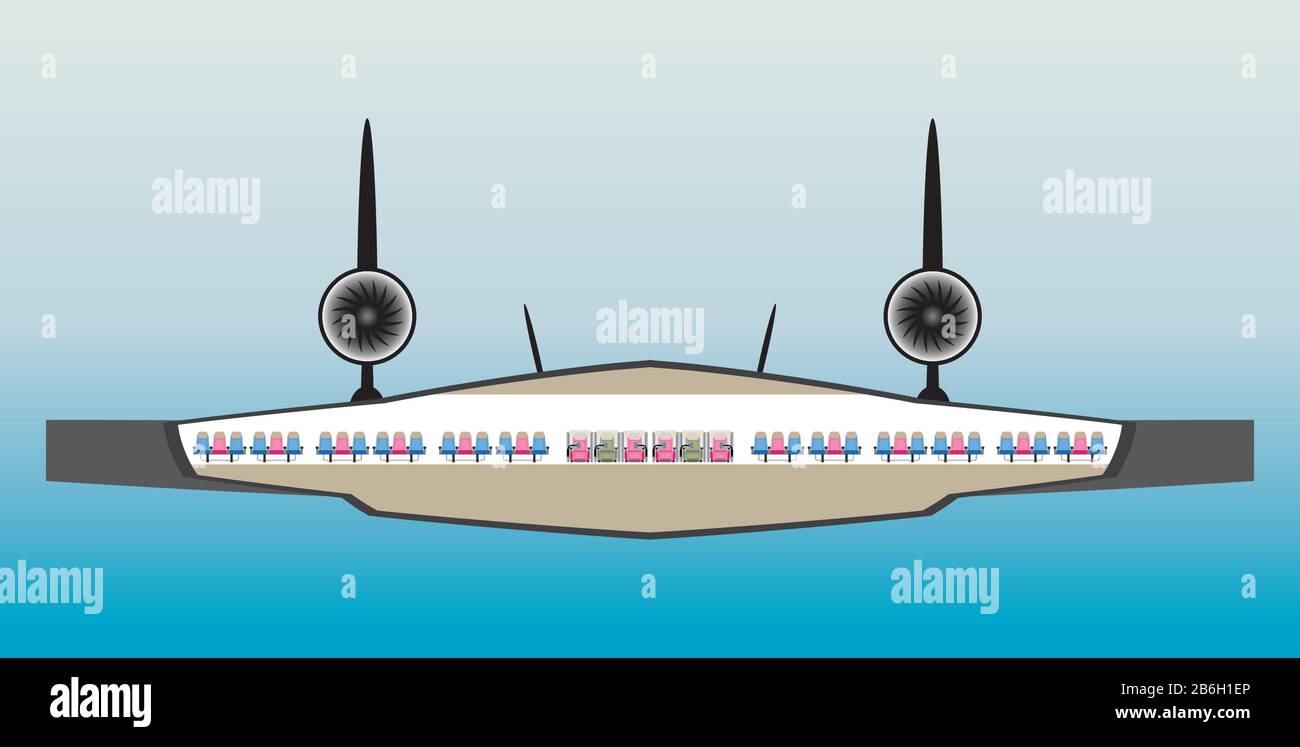

You’re sitting in the window seat, staring out at that massive slab of aluminum or carbon fiber. It looks solid. Static. But if you could slice that wing in half like a loaf of bread, you’d see the airplane wing cross section, or what engineers call an airfoil. This specific shape is the only reason 400 tons of metal can actually stay in the sky without plummeting. It’s not just a flat board. It’s a precision-engineered curve that exploits the very laws of physics to cheat gravity.

Honestly, people get the "how it works" part wrong all the time.

Most of us were taught the "Equal Transit Time" theory in grade school. You know the one: air splits at the front, the air on top has a longer path, so it has to go faster to meet the air on the bottom at the back. It sounds logical. It’s also completely wrong. NASA has been trying to debunk this for years because it implies the air molecules have some sort of "appointment" to keep at the trailing edge. They don't. The real story of the airplane wing cross section is much more interesting and involves a messy, beautiful mix of pressure differentials and flow turning.

The Anatomy of an Airfoil: It’s Not Just a Curve

When you look at a cross section, you’re looking at a few key geometric markers. There’s the leading edge, which is usually rounded to handle air hitting it from different angles. Then there’s the trailing edge, which is sharp as a knife. If the trailing edge weren’t sharp, the air would swirl around and create a massive amount of drag, effectively acting like a parachute you didn't ask for.

The straight line connecting these two points is the chord line.

If the wing is curved more on the top than the bottom—which most are—that's called camber. Camber is what allows a wing to produce lift even when it’s pointed straight ahead. But here’s the kicker: some high-performance planes, like aerobatic stunt pilots use, have perfectly symmetrical airfoils. They look the same on top and bottom. How do they fly? By changing the angle of attack. They literally tilt the wing into the wind to force the air downward.

Physics doesn't care if the wing is pretty. It cares about which way the air is being pushed.

Why the Bernoulli vs. Newton Debate is Kind of Silly

If you hang around pilots or aerospace nerds long enough, you’ll hear them argue about whether lift comes from Bernoulli's Principle (pressure) or Newton's Third Law (action/reaction).

The truth? It’s both. You can’t have one without the other.

When the airplane wing cross section moves through the air, it forces the air to curve. Because of something called the Coanda Effect, air likes to stick to curved surfaces. As the air curves over the top of the wing, it speeds up. This creates a low-pressure zone. Meanwhile, the air underneath is relatively higher pressure. This pressure difference "sucks" the wing upward. That’s Bernoulli.

At the same time, because the wing is angled and shaped the way it is, it deflects a massive amount of air downward. Newton’s Third Law says for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. If the wing pushes air down, the air pushes the wing up.

It’s a total package. If you only look at one side of the equation, you’re missing the forest for the trees.

Supercritical Wings: The Reason We Can Fly Near Mach 1

Ever noticed how modern airliners like the Boeing 787 or the Airbus A350 have wings that look a bit... flat on top?

These are supercritical airfoils. Back in the 1960s, a legendary NASA researcher named Richard Whitcomb realized that as planes got faster, the air moving over the top of the wing would hit supersonic speeds before the plane itself did. This created "shock waves" on top of the wing, which caused a massive amount of drag. It was like hitting a wall in the sky.

Whitcomb’s solution was brilliant. He flattened the top of the airplane wing cross section and gave it a weird little "downward flick" at the back.

- It delays the onset of those nasty shock waves.

- It lets the plane fly faster without burning a hole in the airline's fuel budget.

- It makes long-haul travel actually affordable for the rest of us.

Without the supercritical airfoil, we’d still be stuck flying at 400 mph instead of 550 mph. Those extra 150 mph make a huge difference when you’re crossing the Pacific.

The "Dirty" Secret of Flaps and Slats

Wings are a compromise. A wing shaped for cruising at 35,000 feet is actually terrible at taking off or landing. It’s too "thin" and doesn't produce enough lift at low speeds.

👉 See also: Straight Talk Portable Wifi: Why It Might Be Your Best (Or Worst) Connection Option

This is where the cross section changes in real-time.

When you hear those loud motorized whirs during landing, that’s the pilot changing the actual shape of the wing. They deploy flaps out the back and slats out the front. This effectively increases the camber and the surface area of the airplane wing cross section. Suddenly, that sleek, fast wing becomes a high-lift "bucket" that can stay in the air at 150 mph instead of falling out of the sky.

It’s mechanical shapeshifting.

Real-World Limits: When the Cross Section Fails

Stalling is the nightmare scenario for any pilot, and it’s a direct result of the airflow "detaching" from the wing's cross section.

If you tilt the wing too high (increasing the angle of attack), the air can no longer stick to the upper curve. It becomes turbulent and messy. The low-pressure zone disappears, and the lift vanishes. The wing stops being a wing and starts being a very expensive piece of scrap metal falling through the air.

Designers use "vortex generators"—those tiny little metal tabs you see on top of some wings—to help keep the air energized and stuck to the surface even at steep angles. It’s a tiny fix for a massive physics problem.

What Designers Are Looking at Next

We are moving away from the "static" wing. The future of the airplane wing cross section is likely something called morphing wings.

Instead of having hinges and gaps for flaps, researchers at places like NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center are testing wings that literally bend and twist like a bird's wing. No gaps. No drag. Just a smooth, seamless change in the airfoil shape. This could save billions in fuel costs and make planes significantly quieter.

Practical Insights for Your Next Flight

The next time you’re boarding a plane, take a second to look at the wing from the terminal.

- Spot the Thickness: Notice how thick the wing is where it meets the fuselage. That’s where the "spar" (the wing's spine) is, and where the fuel is stored. The cross section there is huge compared to the tip.

- Look for the "Washout": You might notice the wing seems to twist toward the tip. This is an intentional design choice to ensure that the root of the wing stalls before the tip, allowing the pilot to keep control of the ailerons even during a stall.

- Watch the Flaps: During takeoff, watch the trailing edge. You’ll see the cross section physically grow and curve downward to grab more air.

The airplane wing cross section isn't just a shape; it's a dynamic response to the fluid we call air. It is the result of over a century of trial, error, and some very complex math.

To really understand how these shapes are evolving, you can look into the NACA 4-digit series, which was the first systematic way to categorize these shapes. It’s a rabbit hole of geometry, but it explains why every plane you see today looks the way it does. The era of the "flat" wing is long gone, and the era of the "smart" wing is just beginning.

Check the trailing edge next time you land. You’ll see the "Kutta condition" in action—the point where the air leaves the wing smoothly, proving that the math worked and you’re safely back on the ground.