Space weather is weird. Most of the time, the sun is just a glowing ball of gas that keeps us warm and gives us a tan. But then you get something like Active Region 4087. It sounds like a boring serial number for a car part, doesn't if? Honestly, it's anything but. This massive sunspot group spent its time rotating across the solar disk firing off bursts of energy that essentially slapped Earth's atmosphere. If you noticed your GPS acting funky or your shortwave radio hitting a wall of static during its peak, you weren't imagining things. These AR4087 solar flare blackouts weren't just a "science news" curiosity; they were a localized headache for pilots, mariners, and emergency responders.

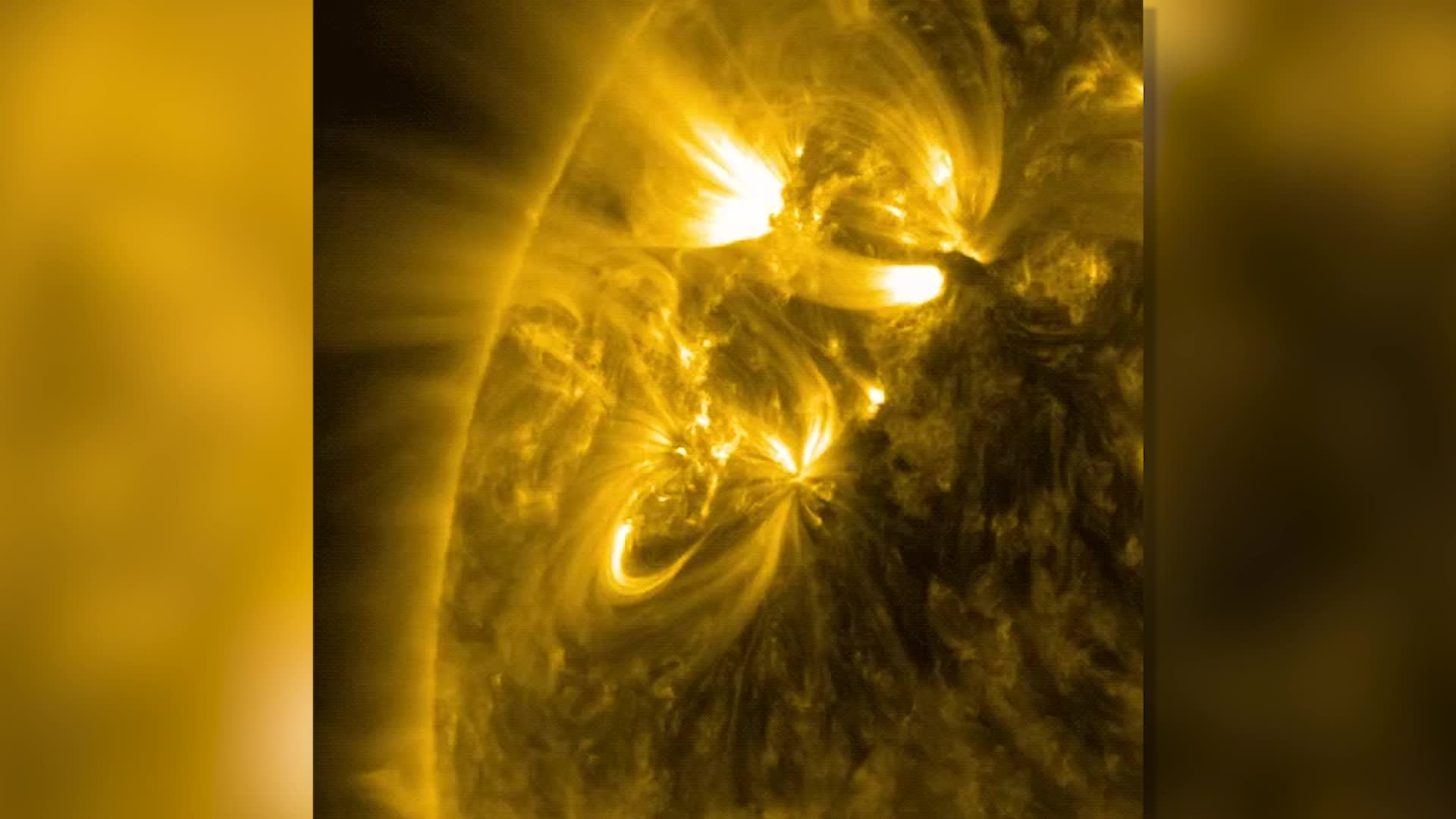

The sun doesn't just shine. It breathes. It pulses. And every roughly eleven years, it gets particularly cranky as it approaches "solar maximum." We are right in the thick of that cycle now. AR4087 was a prime example of a magnetically complex region—what scientists call a "Beta-Gamma-Delta" configuration. That’s just fancy talk for a magnetic mess where positive and negative poles are so tangled up they’re itching to snap. When they do, you get an X-class or M-class flare. The radiation hits us in eight minutes.

Eight minutes. That is no time at all.

What actually happens during an AR4087 solar flare blackout?

When we talk about "blackouts" in this context, we aren't talking about your lights going off at home. Usually. We’re talking about the ionosphere. This is a layer of our atmosphere that acts like a mirror for high-frequency (HF) radio waves. It’s how people talk across oceans without satellites. When AR4087 unleashed its X-flares, a massive wave of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation slammed into this layer. It didn't just heat it up; it ionized the daylights out of it.

Suddenly, that "mirror" became a sponge.

Instead of radio signals bouncing off the ionosphere to reach their destination, they got absorbed. Total silence. If you were a pilot flying a polar route or a HAM radio operator in the Pacific during one of these events, the world just... went quiet. This is technically known as a Shortwave Fadeout. It typically hits the "sunlit" side of the Earth, which makes sense because that’s the part facing the literal explosion.

The NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) uses a scale from R1 to R5 to track these. AR4087 pushed us into the R3 territory—a "strong" radio blackout. At this level, you lose contact for about an hour on the lower frequencies. It’s annoying for some. It’s critical for others.

💡 You might also like: Why Everyone Is Obsessing Over Legalize Comedy Elon Musk Right Now

The technical grit: Why GPS gets wonky

It isn't just radio. GPS (GNSS) relies on timing signals sent from satellites 12,000 miles up. Those signals have to travel through that same messy ionosphere we just talked about. When the density of electrons in that layer spikes because of AR4087 solar flare blackouts, the signal slows down.

Think about it like this. You're trying to time a runner, but suddenly they have to run through waist-deep water instead of air. Your stopwatch is going to be wrong. For a GPS receiver, a delay of even a few nanoseconds translates to a position error of several meters. For a self-driving tractor or a precision drone, that’s the difference between staying on the path and ending up in a ditch.

Why this sunspot was different

Most sunspots come and go. They’re like freckles. But AR4087 was huge—multiple times the size of Earth. It was stable. It lingered. While most spots pop once and decay, this one kept reloading. It showed us that even as we get better at predicting when a flare might happen, predicting the exact impact on our local power grids remains a bit of a dark art.

Wait, did I mention power grids?

Flares themselves don't usually blow up transformers. That’s the job of Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). Think of the flare as the flash of a muzzle, and the CME as the actual bullet. AR4087 was a frequent shooter. When those clouds of plasma hit Earth's magnetic field, they create Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs). These currents crawl into our long-distance power lines. They can saturate transformers. They can cause voltage instabilities. We didn't see a 1989-Quebec-style collapse with AR4087, but the "geomagnetic twitching" was definitely recorded by magnetometers worldwide.

Real-world fallout you might have missed

A lot of the coverage of AR4087 solar flare blackouts focuses on the "what if." But what actually happened?

- Aviation reroutes: Some commercial flights on high-latitude paths had to drop to lower altitudes or change frequencies to maintain communication.

- Maritime frustration: Ships using HF for weather updates found themselves in "dead zones" for stretches of thirty to sixty minutes.

- Starlink struggles: While SpaceX has gotten better at shielding, increased atmospheric drag—a side effect of the atmosphere heating up and expanding—means satellites have to work harder to stay in orbit.

It's a silent storm. You don't hear thunder. You don't see rain. You just see a "Connection Failed" screen on your device or a "No Signal" on a radio.

The "Solar Max" reality check

We are currently approaching the peak of Solar Cycle 25. Experts at NASA and NOAA originally predicted this cycle would be quiet. They were wrong. It's turning out to be much more active than anticipated. AR4087 was just a harbinger.

There's a lot of fear-mongering online about a "Solar Apocalypse." Let’s be real: we aren't going back to the Stone Age. Our grids are more resilient than they were thirty years ago. Engineers use "Faraday cages" and "series capacitors" to block these unwanted currents. But we are more dependent on technology than ever. In 1859, the "Carrington Event" (the big one) just made telegraph machines spark and paper catch fire. If a Carrington-level event happened today, it wouldn't just be the telegraph. It would be the cloud. The banking system. The water pumps.

AR4087 was a warning shot. A "test of the emergency broadcast system" from the universe itself.

How to actually prepare for the next round

Look, you don't need to build a bunker. That’s overkill. But if you’re a tech-heavy business or just someone who likes being informed, there are real things you can do to mitigate the impact of future AR4087 solar flare blackouts.

First, stop relying on a single point of failure for navigation. If you’re hiking or sailing, have an offline map. Physical maps don’t care about the ionosphere. Second, understand that "glitches" during high solar activity are often systemic, not just your device being old.

Actionable steps for the tech-conscious:

- Monitor the scales: Bookmark the SWPC dashboard. Look for the "R" (Radio), "S" (Solar Radiation), and "G" (Geomagnetic) scales. If you see an R3 or higher, expect your GPS to be less accurate.

- Hardwire where possible: If you're running a critical operation, fiber optics are immune to solar interference. Wireless is not.

- Backup Power: Solar flares don't kill batteries, but the grid instability they cause might lead to "dirty power" or surges. Use high-quality surge protectors and Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS) for sensitive server gear.

- Acknowledge the Auroras: On the plus side, G3 or G4 storms mean you can see the Northern Lights much further south than usual. If the radio is dead, go outside and look up.

Space weather is a cost of doing business in a high-tech civilization. We live next to a star. Sometimes, that star gets loud. Understanding that AR4087 solar flare blackouts are a natural, recurring phenomenon helps strip away the panic and replaces it with actual readiness. Keep your firmware updated, keep an eye on the sunspot counts, and maybe keep a paper map in the glovebox. Just in case.

Check your local aurora forecast if a G-class storm is currently active; you might catch a show tonight. If you’re managing sensitive electronics, ensure your grounding systems are up to code to handle any potential induced currents from the next big sunspot group.