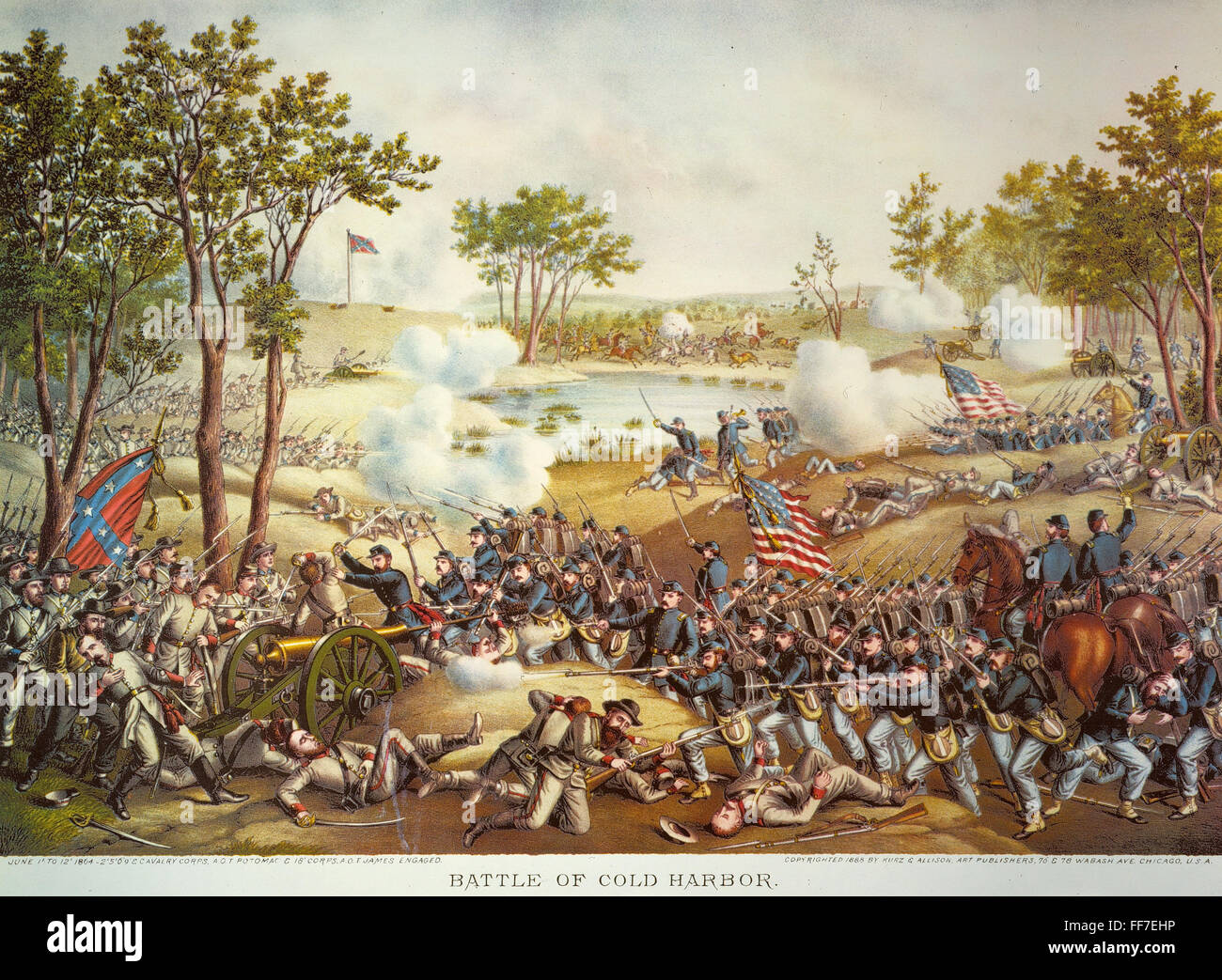

It was a bloodbath. There is really no other way to describe what happened in the dusty crossroads of Hanover County, Virginia, in June 1864. If you look at a Battle of Cold Harbor map, you don't just see troop movements; you see a graveyard drawn in ink. Ulysses S. Grant, a man not known for second-guessing himself, eventually admitted in his memoirs that this was the one attack he truly regretted ordering. He sent waves of men against an invisible, entrenched enemy, and the result was a slaughter so efficient it still feels chilling 160 years later.

The Geometry of a Disaster

Maps from the American Civil War usually show elegant blue and red blocks. They suggest a level of control that simply didn't exist on the ground. When you study the Battle of Cold Harbor map, specifically the lines from June 3rd, you start to see why the Union failed so catastrophically. The Confederate lines, overseen by Robert E. Lee, weren't just straight trenches. They were a sophisticated network of "zig-zags" and salients.

Basically, Lee’s engineers used the terrain to create interlocking fields of fire.

If you were a Union soldier charging across those open fields, you weren't just being shot at from the front. You were being hit from the left and the right simultaneously. This is what military nerds call "enfilade fire." It’s a fancy word for a nightmare. You’re trapped in a pocket of lead. The maps show these V-shaped indentations in the Confederate works that acted like funnels. Once the Union troops entered those "funnels," they had nowhere to go but down.

Why the Maps We Have Today are Different

If you go to the Cold Harbor Battlefield Park now—which is part of the Richmond National Battlefield Park system—the Battle of Cold Harbor map you’ll hold in your hand is a modern reconstruction. It’s clean. It’s easy to read. But the maps used by Grant and George Meade at the time? They were garbage. Honestly, they were worse than useless.

Union leadership was working with outdated or entirely inaccurate sketches of the Virginia interior. They thought they were facing a disorganized Confederate rear guard. They weren't. They were running headlong into a multi-layered defense system that had been perfected over weeks of maneuvering during the Overland Campaign.

The Seven-Mile Line of Death

The scale of the engagement is often lost in history books. We talk about the "Seven Days" or "Gettysburg," but the lines at Cold Harbor stretched for about seven miles.

- The northern flank sat near Bethesda Church.

- The southern end reached down toward the Chickahominy River.

- In the middle was the Old Cold Harbor crossroads—a place that ironically had no water and was nowhere near the coast.

Modern GPS mapping and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) have recently changed how we look at the Battle of Cold Harbor map. LiDAR allows historians to "see" through the dense forest canopy that has grown over the site since 1864. What they’ve found is incredible. The earthworks are still there, scarred into the dirt like permanent wounds. You can see the complexity of the "traverses"—short walls built perpendicular to the main trench to protect soldiers from blasts if a shell landed inside the ditch.

Grant’s men knew what was coming. Legend has it—though it’s well-documented by witnesses like Horace Porter—that many Union soldiers pinned their names and home addresses to the backs of their coats before the June 3rd assault. They weren't being pessimistic. They were being practical. They knew the Battle of Cold Harbor map would eventually be used to mark where their bodies were found.

The Mistake at the "Bloody Angle"

Historians like Gordon Rhea, who wrote the definitive series on the Overland Campaign, point out that the Union actually found a weak spot on June 1st. There was a gap between the divisions of Confederate Generals Hoke and Kershaw. For a brief moment, the Union broke through. But because of poor communication and a lack of clear mapping, they couldn't exploit it.

By the time the massive June 3rd assault happened, Lee had plugged that gap.

If you look at the topographical Battle of Cold Harbor map, you’ll notice a slight rise in the ground where the Confederate center stood. It doesn't look like much—maybe a few feet of elevation—but in the 19th century, that was the difference between life and death. The Union soldiers had to run uphill through waist-high swamp grass and tangled underbrush.

It was over in about twenty minutes.

Some estimates say 7,000 Union men fell in that short window. To put that in perspective: that’s faster than the casualty rate at the D-Day landings in Normandy.

How to Use a Battle of Cold Harbor Map Today

If you’re planning to visit the site, don’t just stick to the main visitor center. The real story is in the "trench trails."

- Start at the Visitor Center: Grab the official National Park Service (NPS) brochure. It has a great overlay of the 1864 positions onto modern roads.

- The Garthright House: This is a crucial landmark on any Battle of Cold Harbor map. It served as a Union hospital. The family hid in the cellar while surgeons worked upstairs; blood allegedly dripped through the floorboards onto them.

- The Garthright Trail: Walk this. It takes you through the Union approach. You can actually stand in the depressions where the soldiers huddled before the "forlorn hope" charge.

- Identify the "Traverses": Look for the zig-zagging mounds of earth. Most people think they're just random hills. They are actually the most preserved Civil War entrenchments in existence.

The maps also reveal the logistical nightmare of the Chickahominy River. After the June 3rd failure, the two armies sat in those trenches for nine days. It was June in Virginia. It was hot. The smell of the dead between the lines was, by all accounts, unbearable. Grant wouldn't ask for a truce to collect the bodies because that would be admitting defeat. Lee wouldn't offer one for the same reason.

The Legacy of the Crossroads

The Battle of Cold Harbor was a tactical masterpiece for Lee and a strategic "win" for Grant, only because he eventually slipped away and headed for Petersburg. But the map tells the truth. It shows an army that was learning the hard way that the era of the "gallant charge" was dead. The age of trench warfare—the precursor to World War I—had arrived.

🔗 Read more: What's the Cost of a Passport: Why You Might Be Paying More Than You Think

If you really want to understand the Battle of Cold Harbor map, you have to look at the "shoupades." These were unique, triangular wooden and dirt fortifications designed by Confederate Brigadier General Francis Shoup. While more famous at the River Line in Georgia, the influence of these high-walled, narrow-aperture defenses is all over the Cold Harbor landscape.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you're diving into this, don't just rely on a Google Image search.

First, go to the Library of Congress digital archives. Search for "Jedediah Hotchkiss maps." He was Lee’s mapmaker, and his sketches are incredibly detailed. You can see the individual farmsteads—Beulah Church, the Watt house—that served as anchors for the lines.

Second, download the American Battlefield Trust app for Cold Harbor. They have an augmented reality feature that overlays the Battle of Cold Harbor map onto your phone's camera view as you walk the trail. It’s the closest thing we have to a time machine.

Finally, compare the Cold Harbor lines to the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House maps. You'll see a pattern. The Union was trying to "left-flank" Lee, and Lee was constantly pivoting like a swinging door to stay between Grant and Richmond. Cold Harbor was the point where the door finally slammed shut, forcing the long siege of Petersburg.

To truly grasp the gravity of this site, find a map that includes the "National Cemetery." It’s located right near the battlefield. Most of the men buried there are "Unknowns." Their names were lost in the very fields the maps tried, and failed, to help them navigate safely.

When you visit, bring a physical map. Cell service in the wooded areas of the park is notoriously spotty, and there is something visceral about holding a paper map while standing in the very trenches it depicts. It makes the history feel less like a textbook and more like a tragedy you can touch.

Move beyond the basic diagrams and look for maps that show the "ravines." These small, marshy creek beds are where the Union soldiers tried to hide when the fire became too intense. Many of them died there, pinned down by sharpshooters for days. It’s a grim reality, but it’s the reality that the Battle of Cold Harbor map preserves for us today.

✨ Don't miss: North Jeolla South Korea: What You're Probably Missing (And Where to Eat)

Explore the site during the late autumn or winter. With the leaves gone, the true "bones" of the battlefield—the ridges, the pits, and the long-lost rifle pits—become visible to the naked eye. That is when the map truly comes to life.