Imagine you're back in 1913. Scientists are scratching their heads. They know the atom has a positive center and negative electrons, but according to the laws of physics at the time, those electrons should just spiral into the nucleus and cause the whole universe to collapse. It was a mess. Then comes Niels Bohr. He basically looked at the chaos and said, "What if the rules are just different for tiny things?"

The Bohr's atomic theory didn't just solve a math problem. It changed how we see reality.

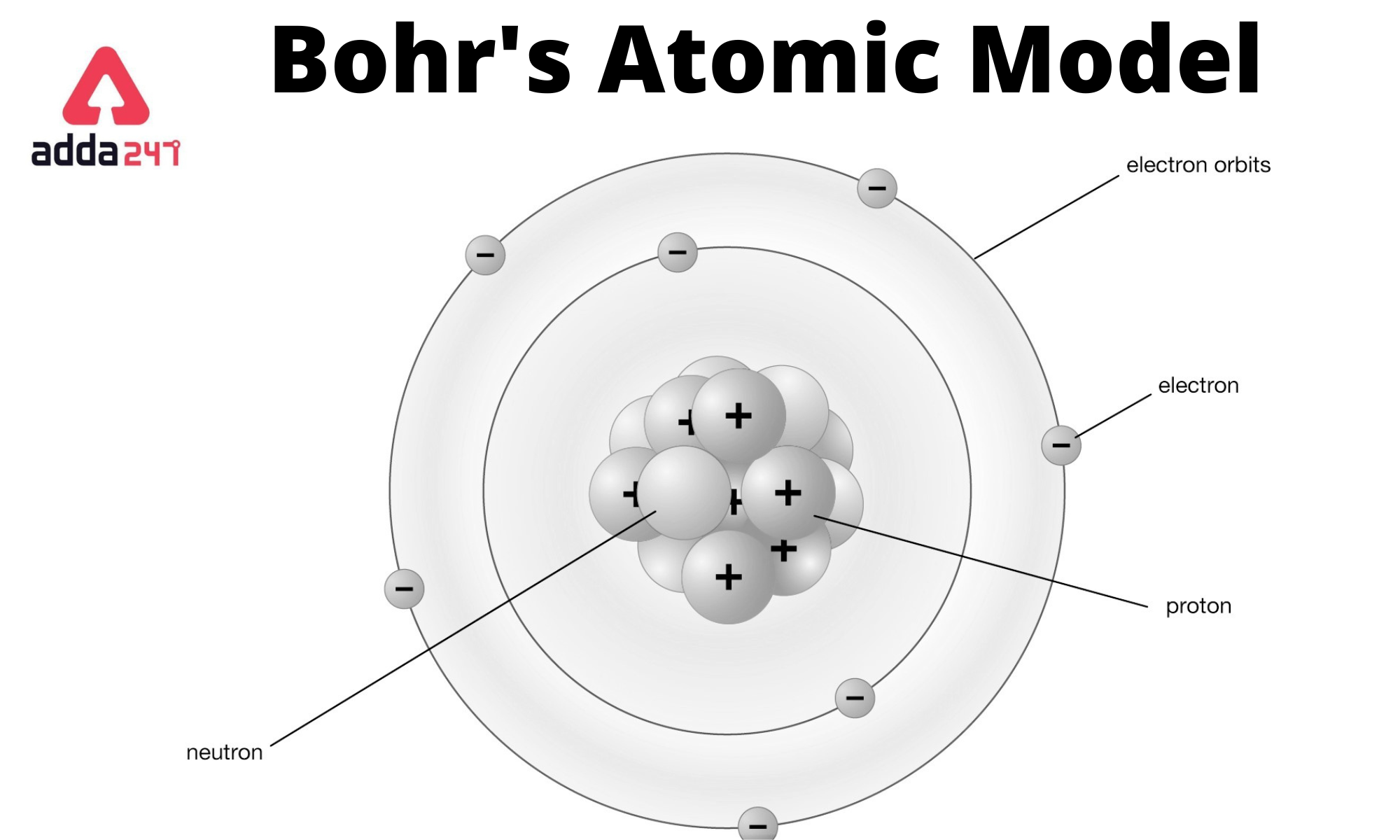

He suggested that electrons don't just float around wherever they want. They're stuck. They have to live in specific "orbits" or energy levels. Think of it like a ladder. You can stand on the first rung or the second rung, but you can’t stand in the empty space between them. If you try, you're going to fall. Electrons are the same way; they exist in these discrete states, and that was a massive, radical leap for science.

The problem with the "Solar System" model

People often call this the planetary model. It’s easy to visualize. You have the nucleus in the middle, like the Sun, and electrons buzzing around like planets. But here’s the thing: planets stay in orbit because of gravity. Electrons are charged particles. According to classical electromagnetism (specifically Maxwell’s equations), a moving charge should radiate energy.

If an electron radiates energy, it loses speed.

If it loses speed, the nucleus pulls it closer.

Boom. The atom should exist for about a billionth of a second before imploding. Since you’re currently sitting there reading this, we know that doesn't happen. Bohr’s brilliance was in his "postulates." He simply declared that in certain stable orbits, electrons don't radiate energy. He didn't necessarily have a "why" yet—that came later with quantum mechanics—but he had the "what."

The magic of quantized energy

Bohr introduced the concept of the principal quantum number, denoted as $n$. This $n$ can be 1, 2, 3, and so on.

When an electron is in the orbit closest to the nucleus ($n=1$), it’s in the "ground state." It’s as chill as it can get. To move to a higher orbit, like $n=2$, it needs a boost. It has to absorb a very specific amount of energy—a photon. If the energy isn't exactly right, the electron ignores it. It’s picky.

✨ Don't miss: One Billion Times One Billion: Why Our Brains Can’t Handle the Quintillion

When that electron eventually gets tired of being in the "excited state" and drops back down, it spits that energy back out as light. This is why we have neon signs. This is why stars have specific colors. Every element has a unique "fingerprint" of light because their energy levels are spaced differently.

Where Bohr actually got it right

We give Bohr a lot of grief because his model is "outdated," but he nailed a few things that remain pillars of modern physics.

- Quantization is real: The idea that energy comes in packets (quanta) rather than a continuous stream is the foundation of everything from your smartphone to MRI machines.

- The Rydberg Constant: Bohr actually calculated the wavelengths of light emitted by hydrogen using his formula, and his results matched experimental data almost perfectly. It was a "drop the mic" moment for 1913.

- Stability: He explained why atoms don't just vanish. By forcing electrons into fixed orbits, he gave the physical world a sense of permanence.

The math for the energy of an electron in a Bohr orbit is actually pretty elegant:

$$E_n = -\frac{13.6 \text{ eV}}{n^2}$$

This tells us that as $n$ gets bigger (further from the nucleus), the energy gets closer to zero, but it’s always negative because the electron is "bound" to the atom. To break free (ionization), you need to get that energy up to zero.

The "Oops" moments: Limitations of the theory

Look, Bohr was a genius, but he was working with limited tools. His model is like a high-quality map of a city that only shows one street. It works great for that street, but you’re going to get lost if you turn the corner.

It only really works for Hydrogen.

Once you add a second electron (Helium), the math falls apart. The electrons start pushing on each other (electron-electron repulsion), and Bohr's simple orbits can't handle the complexity.

The Zeeman Effect.

When you put an atom in a strong magnetic field, its spectral lines split into multiple lines. Bohr’s theory had no explanation for this. It assumed electrons were just dots moving in circles, but they have "spin" and move in complex 3D clouds called orbitals, not flat orbits.

Violating the Uncertainty Principle.

Werner Heisenberg later came along and ruined the party by pointing out that you can't actually know both the position and the momentum of an electron at the same time. Bohr’s model claimed to know exactly where the electron was and how fast it was going. Oops.

Why we still teach Bohr's atomic theory in 2026

You might wonder why we still make students learn this if we know it’s technically "wrong." Honestly, it’s because it’s the perfect bridge. You can't just jump from "balls of matter" to "probabilistic wave-function clouds" without losing your mind.

Bohr’s model provides the vocabulary. We still use terms like "shells" and "valence electrons." We still talk about "jumping" energy levels. It’s a conceptual scaffold. Without Bohr, the leap to Schrödinger and Dirac would be too steep for most people to climb.

Think about the Balmer series. These are the visible lines of light produced by hydrogen. When an electron drops from $n=3, 4, 5, \text{ or } 6$ down to $n=2$, it releases light we can actually see. Bohr explained this. He turned spectroscopy from a guessing game into a precise science.

What this means for you today

If you’re studying chemistry or physics, don’t view the Bohr's atomic theory as a set of rules to be memorized and then discarded. View it as the moment humanity realized the "micro-world" doesn't play by our rules.

It teaches us that:

- Energy isn't infinitely divisible.

- Stability requires specific conditions.

- Observation and math must align, even if the math feels "weird."

If you want to master this, stop trying to visualize electrons as little marbles. Start thinking of them as waves that only fit into specific "vibrations" around the nucleus. That’s the real secret.

Practical steps for mastering atomic structure

If you're prepping for an exam or just trying to sound smart at a dinner party, do these three things:

- Master the transitions: Remember that $E_{high} - E_{low} = hf$. The energy difference between orbits determines the frequency ($f$) of the light emitted. Higher jump = bluer light. Smaller jump = redder light.

- Learn the "Shielding" concept: Understand that Bohr failed on larger atoms because he didn't account for how inner electrons block the nucleus's pull on outer electrons. This explains why the Periodic Table is shaped the way it is.

- Compare the Orbits vs. Orbitals: Remind yourself that Bohr's "orbits" are 2D paths, while modern "orbitals" are 3D probability zones. If you can explain the difference between a circle and a cloud, you’ve outpaced 90% of the population.

Bohr didn't have the whole puzzle, but he found the corner pieces. And as any puzzle enthusiast knows, you can't finish the picture without them.