You know that blinding pop? The one that leaves a purple blob floating in your vision for three minutes? That's the hallmark of a camera with flash bulb setup, and honestly, it’s a vibe that modern LEDs just can't touch. Most people think these things belong in a museum next to top hats and telegrams. They're wrong.

Flash bulbs aren't just "old tech." They are literal chemical explosions contained in glass.

Back in the day, if you wanted to take a photo indoors, you didn't just bump up your ISO. You couldn't. Film was slow. You needed a sun in your pocket. So, engineers stuffed magnesium or aluminum wire into a glass bulb filled with oxygen. When you hit the shutter, a tiny electrical charge ignited that wire. Boom. A massive, singular burst of light that was often brighter than a dozen modern Speedlites combined.

The Physics of a Controlled Explosion

It’s kinda wild when you think about it. Modern electronic flashes (strobe) work by passing high-voltage electricity through xenon gas. It’s fast. It’s repeatable. But a camera with flash bulb is a one-and-done deal. Once that wire burns, the bulb is dead. It’s garbage. You’d see photographers at weddings in the 1950s with pockets bulging with used, scorched glass.

Why does it look different?

It’s all about the "burn time." An electronic flash is instantaneous—usually between $1/1000$ and $1/50,000$ of a second. A flash bulb, however, has a "ramp-up" period. It takes a few milliseconds to reach peak brightness and a few more to fade out. This creates a "long" flash duration. Because the light lingers, it fills a room in a way that feels organic. The shadows aren't quite as harsh, and the skin tones get this weird, creamy glow that digital filters try—and fail—to emulate.

Sync Speeds and the M-Sync Struggle

If you’ve ever messed with an old Leica or a Graflex Speed Graphic, you’ve probably seen a switch for "X" and "M" sync.

- X-Sync is for electronic flash. It fires the flash the exact microsecond the shutter is fully open.

- M-Sync is specifically for the camera with flash bulb.

Because the bulb needs time to start burning before it reaches full brightness, the camera actually triggers the flash before the shutter opens. If you use a flash bulb on X-sync, your shutter will open and close before the bulb even gets bright. You'll get a black frame. It’s a frustrating lesson to learn the hard way. Trust me.

The Iconic Gear: From Press Cameras to Pocket Instamatics

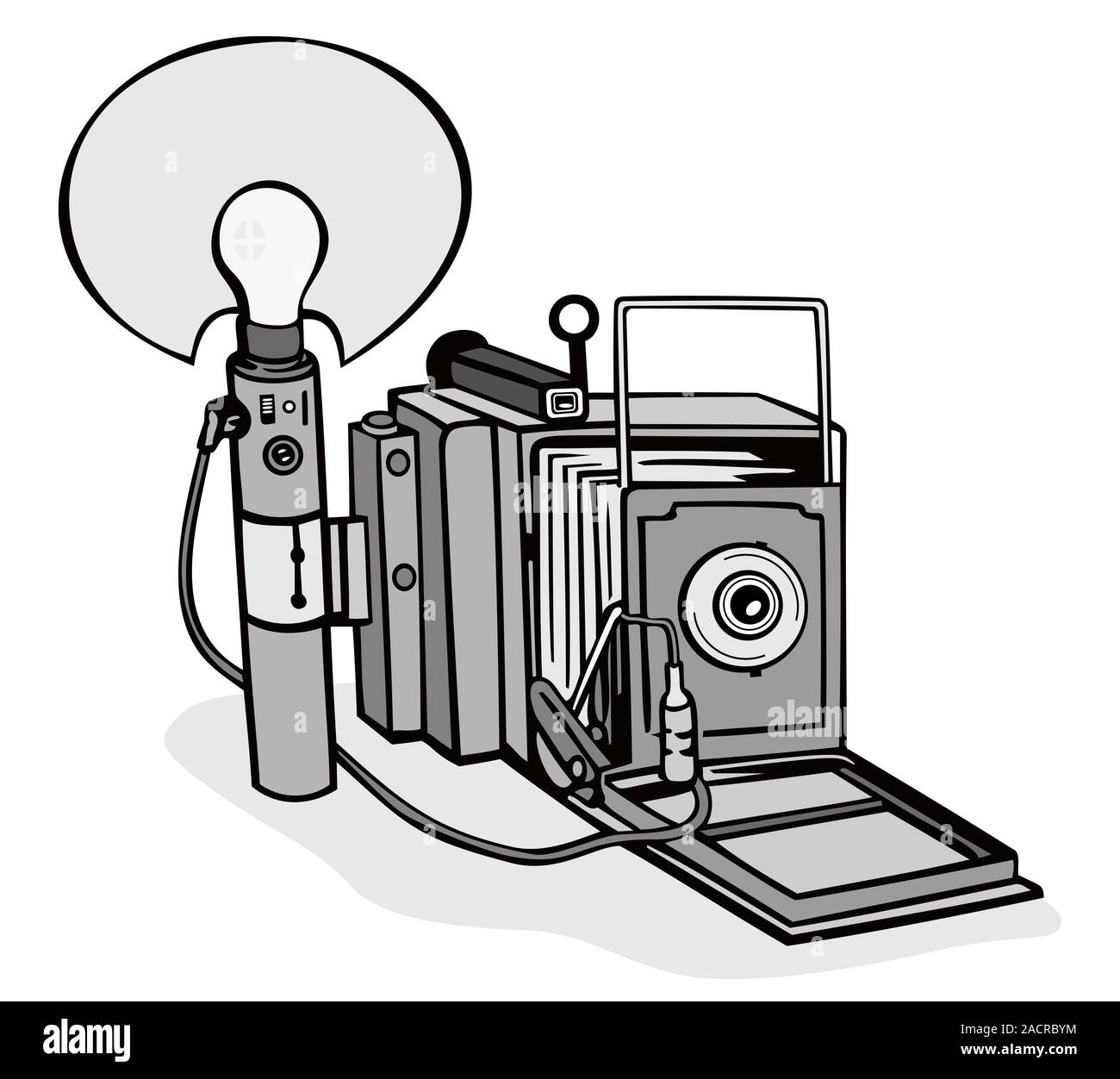

When most people picture a camera with flash bulb, they see a 1940s press photographer. He’s holding a massive 4x5 Speed Graphic with a "potato masher" flash handle and a 7-inch polished reflector. These used the big bulbs—the Sylvania Type 2 or the GE No. 5. These bulbs were about the size of a standard household lightbulb. They were powerful enough to light up a dark alleyway from fifty feet away.

But then things got smaller.

By the 1960s, we had the Flashcube. This was a stroke of genius from Kodak. It was a little plastic cube with four tiny bulbs and four individual reflectors. You’d pop it onto your Instamatic, take a shot, and the camera would mechanically rotate the cube to the next fresh bulb. You got four shots before you had to toss the cube. It made photography accessible. No more burning your fingers on hot glass—though those cubes still got plenty warm.

Later came the "FlipFlash." It was a long strip of bulbs. You’d use the top half, then flip it over to use the bottom half. It was basically the last gasp of chemical flash technology before high-efficiency electronics became cheap enough for the masses.

Why Professionals Still Hunt for New Old Stock (NOS)

Believe it or not, there is a niche market for these things today. High-end fashion photographers and certain "slow photography" enthusiasts scour eBay for Sylvania Blue Dots.

🔗 Read more: Wait, What is IDM in Text? The Real Meaning Behind the Slang

Why? Because of the sheer volume of light.

A large flash bulb like the Meggaflash PF330 can put out a staggering amount of lumens. If you’re trying to overpower the midday sun while shooting on large format film with a tiny aperture (like $f/64$), a standard battery-powered flash might not cut it. You’d need a massive, expensive power pack. Or, you could just use one $10 vintage flash bulb.

There’s also the color temperature. Most bulbs were coated with a blue plastic (hence the "Blue Dot" name) to match the color temperature of daylight film. As that plastic heats up and the metal burns inside, you get these tiny, unpredictable shifts in color. It creates a "soul" in the photo. It’s imperfect.

The Danger Factor (Seriously, Be Careful)

We have to talk about the "splatter."

Early flash bulbs were notorious for exploding. Not just the wire inside—the actual glass. This is why many vintage flash units had a plastic shield over the reflector. If the glass had a microscopic crack, the heat of the ignition would cause the bulb to shatter outward. If you’re using a camera with flash bulb today, check your glass. If the blue safety spot has turned pink or clear, the seal is broken. Do not fire it. It’s essentially a small grenade.

Also, they get hot. Really hot. If you try to pull a bulb out of the socket immediately after firing, you’re going to lose some skin. Experienced shooters usually waited a few seconds or used a handkerchief to eject the spent hull.

The Aesthetic: How to Spot the Difference

You can usually tell if a photo was taken with a flash bulb versus a modern strobe by looking at the "fall-off."

Electronic flash tends to be very "point-source." It creates a hard line between light and shadow. Flash bulbs, because of the way the light builds and decays, seem to "wrap" around subjects a bit more. There’s a richness to the blacks.

In the world of 2026, where every smartphone photo looks perfectly processed and HDR-balanced, the "flash bulb look" is a rebellion. It’s high-contrast, it’s dramatic, and it has a certain "newsprint" grit to it. Think of the famous Weegee photographs—the gritty crime scenes of New York. That look is entirely dependent on the specific burn of a magnesium bulb.

Getting Started With Flash Bulb Photography Today

If you’re itching to try this, don’t just go buying random stuff on Etsy. You need a plan.

- Find the Hardware: Look for a camera with a dedicated flash sync. A Rolleiflex or a vintage 35mm rangefinder with a PC sync port is perfect.

- The Flash Unit: You’ll need a "B-C" (Battery-Capacitor) flash gun. These usually take 15V or 22.5V batteries, which are still made but can be pricey. The capacitor is key because it provides the sudden "jolt" needed to ignite the wire.

- The Bulbs: Look for "New Old Stock." Brands like Sylvania, GE, and Westinghouse are the gold standard. Common sizes are M2, M3, or the larger No. 5. Make sure the base matches your flash (Bayonet vs. AG-1).

- Exposure Math: This is the hard part. Flash bulbs use "Guide Numbers." You divide the Guide Number by the distance to your subject to find your aperture. For example, if your GN is 80 and your subject is 10 feet away, you set your lens to $f/8$.

It’s tactile. It’s loud. It smells like ozone and burnt metal. It’s a far cry from tapping a screen on an iPhone.

Practical Insights for the Modern Shooter

If you want the "look" without the expense of $5-per-shot bulbs, you can fake it, but only to a point. Use a warm-toned gel on your electronic flash and set your shutter speed slightly slower than usual to pick up some ambient "burn."

But honestly? If you want the real deal, there’s no substitute for the chemical reaction.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Check the seals: Before buying any vintage bulbs, ensure the "safety dot" is blue. If it's pink, the vacuum is gone, and the bulb is a dud or a hazard.

- Clean your contacts: Old flash guns often have corrosion. A bit of sandpaper on the battery terminals and the bulb socket will save you a lot of "misfire" heartbreak.

- Scout the "M-Sync": If your camera doesn't have an M-sync setting, you can still use flash bulbs! You just have to use a "T" (Time) or "B" (Bulb) shutter setting. Open the shutter manually, fire the flash, then close the shutter. It’s how the pioneers did it.

- Dispose properly: Remember, these are glass and contain trace metals. Don't just toss them in the woods.

The camera with flash bulb era was a time when light was something you carried in boxes, one explosion at a time. It forced photographers to be deliberate. You didn't "spray and pray" when every click of the shutter cost you a bulb. That discipline is something every modern photographer could stand to learn.