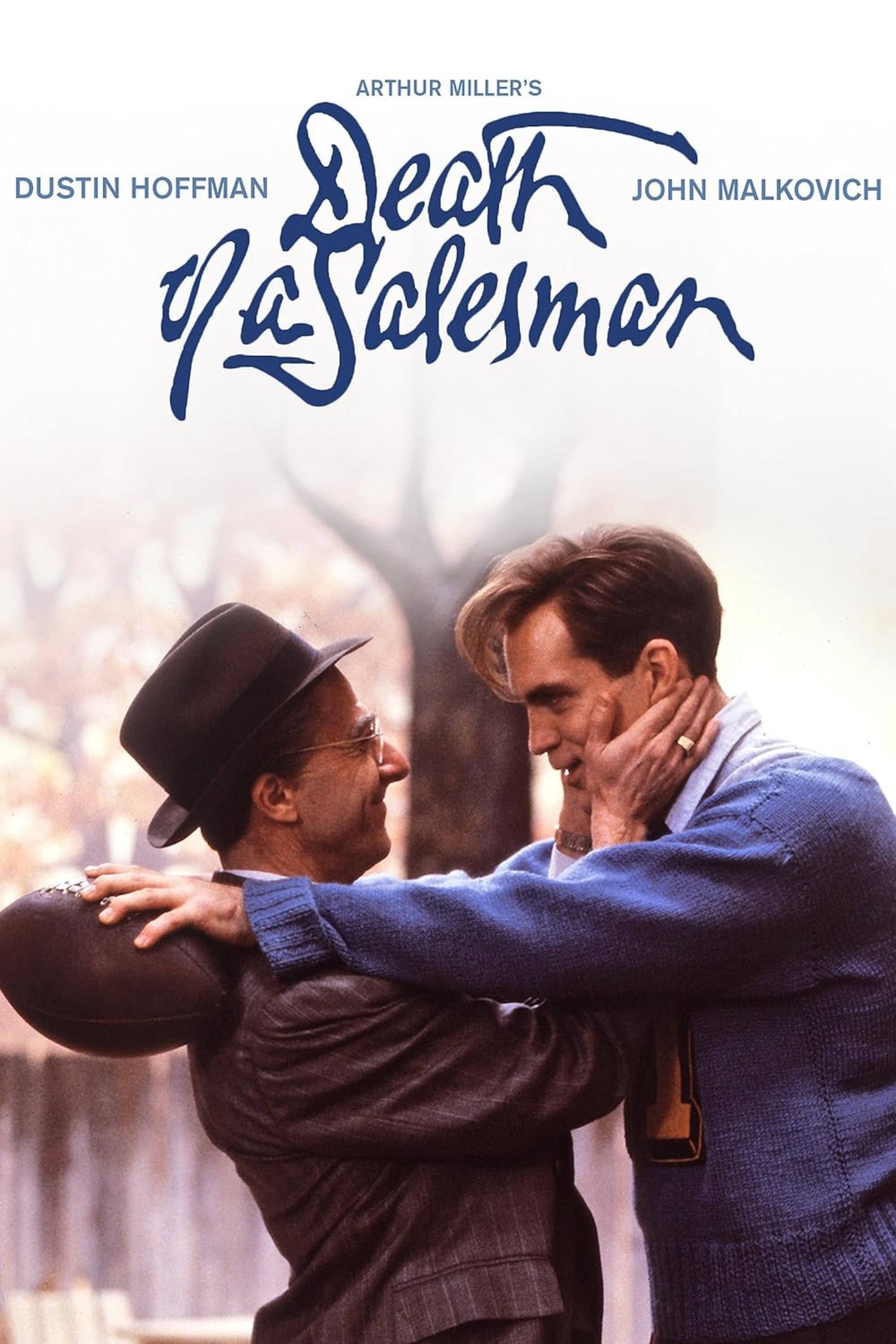

Watching Dustin Hoffman play Willy Loman in the Death of a Salesman 1985 film is a weirdly claustrophobic experience. It isn't just a movie. It’s a recorded stage play, really, and it feels like the walls are physically closing in on the Loman family. If you've ever felt that crushing weight of "not being enough" or the anxiety of a bank account that just won't stay in the black, this version of Arthur Miller's masterpiece is going to resonate. Hard.

It’s brutal.

Most people know the story from high school English class. Willy Loman is a failing salesman who has bought into a version of the American Dream that doesn't actually exist. He thinks being "well-liked" is the secret to success. He’s wrong. By the time we meet him in the 1985 production, he’s losing his mind, drifting between the grim reality of his Brooklyn home and the golden-hued memories of a past that probably wasn't as great as he remembers.

📖 Related: Tracy Tutor Ex Husband: What Really Happened with Jason Maltas

Why the Death of a Salesman 1985 Adaptation Changed Everything

Before this version, people usually thought of Willy Loman as a big, hulking guy—someone like Lee J. Cobb, who originated the role. Cobb was massive. When he collapsed, it was like a giant oak tree falling. But Dustin Hoffman changed the game.

He’s small.

He’s scrappy.

He looks like a man who has been physically shrunk by the weight of his sample cases. This was a deliberate choice by director Volker Schlöndorff. By casting Hoffman, the production leaned into the idea that Willy is a "shrimp," a word Willy actually uses to describe himself in the play. It makes his desperation feel more frantic and, honestly, more pathetic in a way that breaks your heart.

The Death of a Salesman 1985 movie didn't try to hide its theatrical roots. It was filmed on stylized sets that didn't look like a real neighborhood. You can see the artifice. You see the skeletons of houses. This was intentional. Arthur Miller himself was heavily involved in this production, and he wanted that dreamlike, expressionistic vibe. It forces you to focus on the performances rather than the scenery.

John Malkovich plays Biff Loman, and if you want to see a masterclass in "daddy issues," this is it. Malkovich brings this whispery, simmering rage to the role. He’s the son who realized his father is a fake, and he can’t figure out how to live his own life because of it. The chemistry between Hoffman and Malkovich is tense. You can feel the spit flying during their arguments. It’s uncomfortable to watch, which is exactly why it’s good.

The Problem With the American Dream

Willy Loman’s tragedy isn't that he failed. It’s why he failed. He believed that if you're "personally attractive" and "well-liked," you’ll never lack for business. He tells his sons, Biff and Happy, that "the man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead."

He was sold a lie.

In the Death of a Salesman 1985 version, you see the fallout of this philosophy. Willy’s neighbor, Charley (played by Stephen Lang), is the opposite. Charley isn't "well-liked" in the way Willy defines it. He’s just a guy who worked hard and didn't talk much about it. Charley’s son, Bernard, becomes a successful lawyer while Willy’s sons are drifting through life, stealing and lying to keep up appearances.

There’s a scene where Willy goes to his young boss, Howard, to ask for a desk job so he doesn't have to travel anymore. Howard doesn't care about Willy’s history with the company. He’s obsessed with a new wire recorder—a gadget. It’s a cold, capitalist moment that feels incredibly modern. Replace the wire recorder with an AI tool or a new CRM system, and it’s the exact same conversation happening in corporate offices today. Willy is obsolete, and the realization kills him.

Breaking Down the Performances That Made It Iconic

Let’s talk about Kate Reid as Linda Loman. Often, Linda is played as a doormat. She’s the long-suffering wife who just takes it. But in the Death of a Salesman 1985 film, Reid gives her a backbone of steel. When she delivers the famous "Attention must be paid" speech, she isn't just crying; she’s accusing her sons. She knows Willy is a "small man," but she demands he be treated with dignity.

It’s a heavy burden for a woman to carry. She’s the one holding the family’s finances together, literally counting the pennies while Willy hallucinates about his brother Ben in the backyard.

Speaking of Ben, the way he’s handled in this version is fascinating. He appears out of the shadows, looking like a ghost from a different era. He represents the "get rich quick" fantasy—the guy who went into the jungle at 17 and came out at 21, rich. He is the personification of Willy’s regrets. Every time Ben appears, the lighting shifts. It’s a visual cue that Willy’s mind is fracturing.

The 1985 production also features Stephen Lang as Happy Loman. Most people know Lang from Avatar or Don't Breathe as this tough, gritty actor. Seeing him here as the younger, desperate-to-please, slightly sleazy Happy is a trip. He perfectly captures the "forgotten" son who tries to win his father’s love by lying about his professional success.

Why Does This 1985 Version Matter Now?

We live in a world of LinkedIn "thought leaders" and Instagram influencers who curate every second of their lives. We are, in many ways, more obsessed with being "well-liked" and "personally attractive" than Willy Loman ever was. The Death of a Salesman 1985 adaptation acts as a mirror.

It asks: What happens when the image you've built doesn't match the reality of your life?

Willy’s greatest fear wasn't death; it was being forgotten. He wanted a funeral like Dave Singleman, the legendary salesman who could make a sale from his hotel room just by picking up the phone. Singleman died "the death of a salesman," with hundreds of people at his funeral. Willy thought that was the ultimate achievement.

The reality of Willy's funeral is the final gut-punch of the story. Hardly anyone shows up.

It’s a stark reminder that the "personal interest" Willy spent his life building was shallow. He didn't have real friends; he had contacts. He didn't have a career; he had a territory. When he couldn't produce, the system chewed him up and spat him out. Miller’s critique of capitalism is loud and clear here, but it’s the human cost that really sticks with you.

Crucial Insights for Modern Viewers

If you're going to sit down and watch the Death of a Salesman 1985 film, keep an eye on the props. The sample cases, the refrigerator that keeps breaking, the flute music that plays in the background—these aren't just details. They are symbols of a man trying to hold onto a world that has already passed him by.

The "flute" is a callback to Willy's father, who was a flute maker and a traveler. It represents a different kind of life—one based on craftsmanship and genuine exploration, rather than selling someone else's products. Willy chose the wrong path. He chose the "selling" life because he thought it was the way to be a "big man."

There are a few things you should do to get the most out of this film:

- Pay attention to the lighting changes. When the color shifts to a warm, golden hue, you're in Willy's memory. When it’s cold and blue/grey, you're in the miserable present.

- Watch Biff’s eyes. John Malkovich does incredible work showing the moment Biff realizes his father is a fraud. It’s the turning point of the entire play.

- Listen to the silence. Unlike modern movies that use a constant soundtrack, this version uses silence to emphasize the emptiness of the Loman house.

Basically, this movie is a warning. It’s a warning about basing your self-worth on your job title or your popularity. It’s about the danger of living in the past and the necessity of facing the truth, no matter how much it hurts.

Willy Loman isn't a hero, but he’s not a villain either. He’s just a man who didn't know who he was. As Biff says at the end: "He had the wrong dreams. All, all wrong."

To truly understand the impact of the Death of a Salesman 1985 production, you have to look at how it treats the "Requiem" at the end. It doesn't offer easy answers. It leaves you feeling a bit hollow. But that hollowness is the point. It’s meant to make you walk away and look at your own life, your own career, and your own family, and ask yourself what’s real and what’s just "sunshine and sell."

The best way to experience this is to watch it in one sitting. Don't scroll on your phone. Let the staginess of the production settle in. Let the claustrophobia of the Loman house get under your skin. By the time the credits roll, you’ll understand why this specific version is considered the definitive filmed record of Miller's work. It’s uncomfortable, it’s loud, it’s tragic, and it’s arguably one of the most important pieces of American media from the 1980s.

Look for the subtle differences in how Willy talks to his sons versus how he talks to his boss. The code-switching is fascinating. He’s a different man depending on who he’s trying to impress. That’s the core of his tragedy—he’s a man who has lost his "self" in the process of trying to be "somebody."

If you've ever felt the pressure to perform or the fear of falling behind, you owe it to yourself to see how Hoffman and company handled those universal anxieties back in 1985. It’s a timeless story that, unfortunately, only becomes more relevant as the years go by. It’s a hard watch, but a necessary one. Sorta makes you want to go outside and plant a garden, just like Willy tried to do at the end. Something real. Something that will grow. Something that isn't just talk.

For anyone looking to dive deeper into the themes of the Death of a Salesman 1985 film, start by comparing the "Requiem" scene with the opening "Entrance" scene. Notice how the hope that existed (even if it was fake) at the beginning has been completely extinguished by the end. The transformation in Hoffman’s physical stature throughout the film—from a man trying to stand tall to a man literally doubled over—is the most honest piece of acting you're likely to see.

Take the time to watch it without distractions. Focus on the dialogue, specifically the cadence that Dustin Hoffman uses, which mimics the real-life rhythms of a Brooklyn salesman from that era. It’s not just a performance; it’s a preservation of a very specific type of American identity that was already disappearing when the film was made.