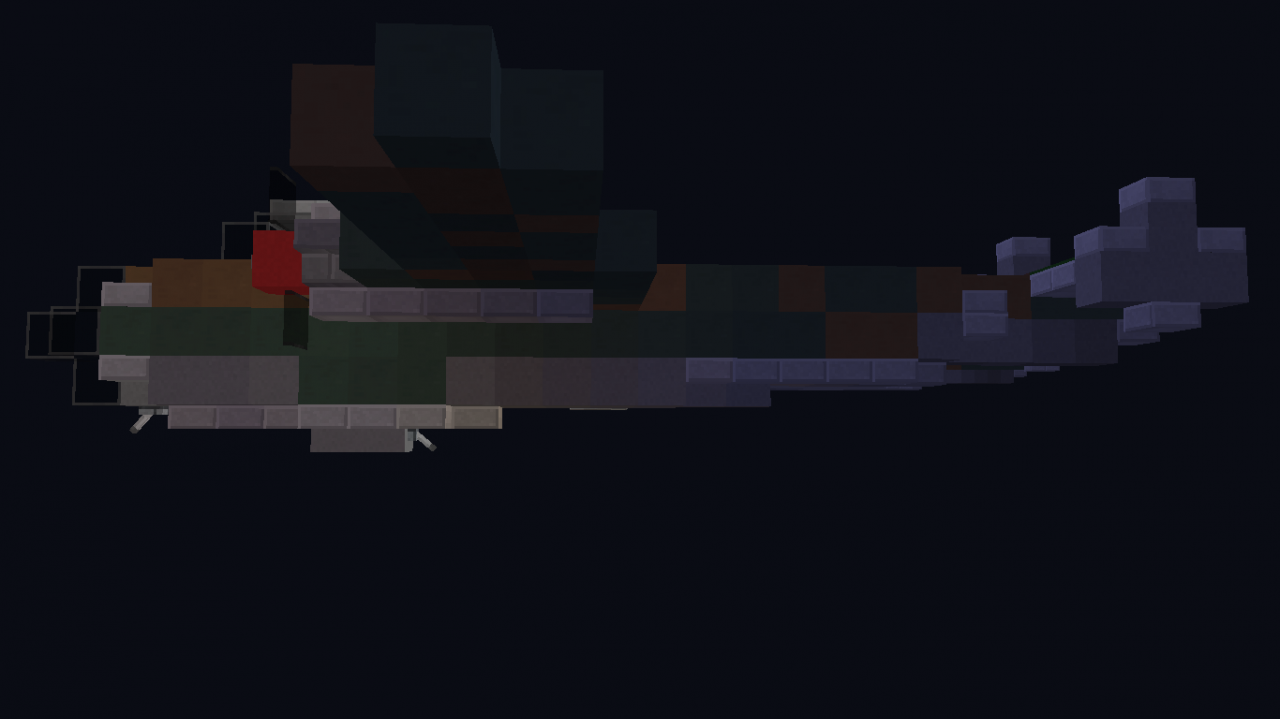

When you look at the Dornier Do 17 bomber, it doesn't look like a weapon of mass destruction. It looks like a pencil with wings. Honestly, that’s exactly what the crews called it: the Fliegender Bleistift. The Flying Pencil. It was sleek, impossibly thin, and looked more like a racing plane than something meant to carry a ton of high explosives over London or Warsaw. But don't let the skinny fuselage fool you. This aircraft was the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s early blitzkrieg campaigns, even if it eventually got overshadowed by the beefier Heinkel He 111 and the versatile Junkers Ju 88.

People often dismiss the Do 17 as a failure because it was being phased out by 1941. That’s a bit of a shallow take. You’ve got to remember that when it first showed up at the Zurich Central Military Aircraft Competition in 1937, it absolutely embarrassed the world’s best fighters. It was faster than almost anything that tried to catch it. In those early years, the Dornier Do 17 bomber wasn't just a participant; it was a statement of German aeronautical dominance.

📖 Related: My Amazon Library Kindle: Where Your Books Go and How to Actually Find Them

The Secret Origin of the Flying Pencil

The story of the Dornier Do 17 bomber is basically a tale of high-stakes corporate deception. Back in the early 1930s, Germany was still technically hamstrung by the Treaty of Versailles. They weren't supposed to have a real air force, let alone a fleet of bombers. So, Claude Dornier’s team designed the Do 17 under the guise of a "commercial mail plane" for Deutsche Luft Hansa.

The design was radical.

To keep drag to an absolute minimum, the fuselage was made incredibly narrow. It was so tight inside that the crew of four sat in a cramped "battle station" in the nose. There was no walking around. You couldn't just get up and stretch your legs. If you were the navigator, you were basically sitting on top of the pilot. Luft Hansa actually rejected the initial prototypes because the cabin was too small for passengers. They said it was useless for mail. It was a failure as a civilian plane, and for a moment, the project almost died.

Then, the military stepped in.

The Luftwaffe saw exactly what Dornier had built: a high-speed sprint bomber. By 1937, the Do 17 E-1 and F-1 variants were rolling off the assembly lines. They featured two BMW VI engines and a range that, at the time, seemed revolutionary. It was the "fast bomber" concept (Schnellbomber) in its purest form. The idea was simple: if you're faster than the enemy's interceptors, you don't need heavy armor or massive defensive guns. You just outrun the problem.

Performance in the Spanish Civil War and Beyond

When the Condor Legion took the Dornier Do 17 bomber to Spain, the theory held up. Republican fighters, mostly older biplanes or early Soviet I-15s, simply couldn't catch the Dorniers. It was a ghost. This success gave the German high command a bit of a false sense of security. They started believing that speed alone would protect their crews forever.

By the time 1939 rolled around, the Do 17 had evolved into the Z-series. This is the version most historians focus on. The Do 17Z featured a much larger, "beetle-eye" cockpit to give the crew more room and better visibility for defensive fire. It used Bramo 323 Fafnir radial engines. These were tough. They could take a lot of punishment, but they also made the plane look a bit more rugged and less like the "pencil" of its youth.

The Reality of the Battle of Britain

The summer of 1940 was the turning point. This is where the Dornier Do 17 bomber met its match.

The Royal Air Force's Hurricanes and Spitfires were a different breed of cat compared to what the Germans had faced in Spain or Poland. Suddenly, the "fast bomber" wasn't fast enough. The Do 17Z had a top speed of roughly 255 mph. A Spitfire Mk I could do 350 mph. The math just didn't work in the Luftwaffe's favor anymore.

During the Battle of Britain, the Dornier suffered heavy losses. Because its bomb load was relatively small—only about 2,200 lbs—it had to fly in tight formations to be effective. This made them prime targets for British radar-directed interceptions. Pilots like the legendary Douglas Bader and Robert Stanford Tuck found that while the Dornier was highly maneuverable for a bomber, it lacked the "reach" to survive the journey back across the Channel if it got strayed from its fighter escort.

Why Pilots Actually Liked Flying It

Despite the losses, if you talk to aviation buffs or read the memoirs of former Luftwaffe pilots, you'll find a weird amount of affection for the "Flying Pencil." It was famously easy to fly.

Unlike the Heinkel He 111, which felt like a heavy truck, the Do 17 handled more like a heavy fighter. It was responsive. It was also surprisingly durable. There are accounts of Do 17s returning to base with hundreds of bullet holes and large chunks of the tail missing. The Bramo radial engines were air-cooled, meaning they didn't have a vulnerable liquid-cooling system that would seize up the second a single piece of shrapnel hit a radiator.

It was a pilot's airplane.

- Agility: It could dive faster than most contemporary bombers without shedding its wings.

- Maintenance: Ground crews loved it because the systems were accessible and the engines were reliable.

- Visibility: The "beetle-eye" nose offered a panoramic view, which was great for low-level navigation, though it felt like living in a glass bowl during a dogfight.

The Do 17 was also remarkably versatile for its size. Beyond just dropping bombs, it served as a reconnaissance platform, a glider tug, and eventually, in its Do 215 and Do 217 iterations, a night fighter. The Do 17Z-10 "Kauz" was a dedicated night fighter version equipped with an infrared searchlight and a nose full of machine guns and cannons. It was the ancestor of the high-tech interceptors that would haunt the RAF’s Bomber Command later in the war.

Technical Nuance: The Radial vs. Inline Engine Debate

One thing most people get wrong about the Dornier Do 17 bomber is the engine situation. The early models (E and F) used BMW VI inline engines. These were sleek and fit the "pencil" aesthetic perfectly. However, the switch to the Bramo 323 radial engines for the Z-series was a trade-off.

Radial engines create a lot of drag. They’re basically big circles pushing against the air. But they are much harder to kill. In the chaos of 1940, the Luftwaffe decided that survivability was more important than a few extra miles per hour of top speed. This shift actually changed the silhouette of the plane significantly, making the "Flying Pencil" look a bit more like a "Flying Cigar."

The End of the Line and the Do 217

By 1941, production of the original Do 17 ceased. It was replaced by the much larger, much more powerful Dornier Do 217. While the 217 looked similar, it was a completely different animal, capable of carrying four times the bomb load and equipped with much heavier defensive armament.

The remaining Do 17s were shipped off to the Eastern Front or handed over to allies like Finland and Bulgaria. In the freezing conditions of the Soviet Union, the Do 17’s reliability was a godsend. It could operate from rough, unpaved airfields that would have broken the landing gear of more delicate aircraft. Finnish pilots, in particular, used their Do 17s with incredible efficiency, keeping them flying long after the Luftwaffe had relegated the type to training duties.

What Really Happened to the Survivors?

Sadly, almost all of these planes were scrapped after the war. For decades, there wasn't a single complete Dornier Do 17 bomber left in the world. It was a "ghost plane" known only through black-and-white photos and grainy newsreels.

That changed in 2013.

A Do 17Z-2 that had been shot down during the Battle of Britain was discovered submerged in the Goodwin Sands off the coast of Kent. The Royal Air Force Museum managed a miraculous recovery, lifting the wreck from the seabed. Seeing the "Flying Pencil" emerge from the water after 70 years was a massive moment for historians. It’s currently undergoing long-term conservation at Michael Beetham Conservation Centre at RAF Cosford. Looking at that corroded airframe, you can see just how thin the aluminum skin was—truly a pencil with wings.

🔗 Read more: How to Share Instagram Post on Instagram: The Parts Everyone Always Misses

Final Insights on the Do 17 Legacy

The Dornier Do 17 bomber shouldn't be remembered just as a failure of the Battle of Britain. It was a victim of its own early success. It was designed for a 1935 world, and by 1940, the world had moved on. It represents the peak of mid-30s aerodynamic thought—the belief that speed could replace armor.

If you're looking to dive deeper into the history of this aircraft, here’s how to actually experience its history today:

- Visit RAF Cosford: You can see the recovered Goodwin Sands Dornier in person. It’s still in a "preserved" state of decay, which honestly makes it look more haunting and real than a shiny museum restoration.

- Study the Finnish Air Force archives: The Finns kept meticulous records on their Do 17 fleet, providing the best data on how the plane performed in extreme cold.

- Compare the variants: Look at the Do 17P (reconnaissance) versus the Do 17Z. The change in the nose design tells the entire story of how air combat evolved in just three short years.

The Dornier was a transitional machine. It bridged the gap between the biplanes of the Great War and the heavy, four-engine "heavies" that would eventually dominate the skies. It was elegant, cramped, fast, and ultimately outpaced by the very technology it helped pioneer.