You know that feeling when you're watching a show from sixty years ago and it somehow feels more relevant than anything on Netflix right now? That’s the magic of Rod Serling. But specifically, it’s the magic of The Eye of the Beholder, perhaps the most famous episode of The Twilight Zone ever produced. It first aired on November 11, 1960. Think about that for a second. We were still years away from the Civil Rights Act, yet here was a black-and-white teleplay screaming at us about the absolute insanity of social conformity.

It’s visceral.

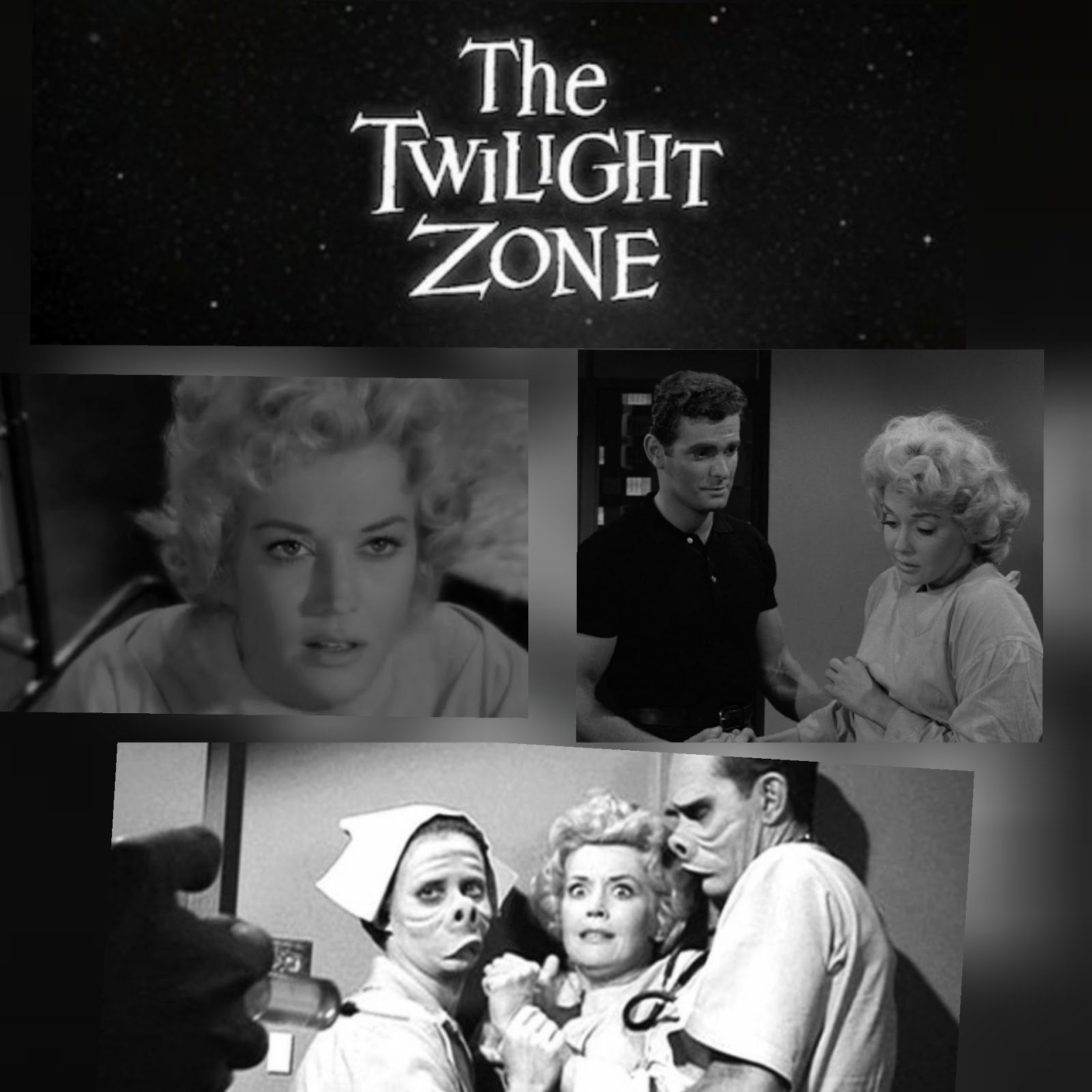

The plot is deceptively simple, which is why it works. We follow Janet Tyler, a woman whose face is wrapped in bandages. She’s undergone her eleventh—and final—surgical attempt to look "normal." If this one fails, she’s headed for a colony of her own "kind." You don’t see the doctors' faces. You don't see the nurses. The camera hangs over shoulders, lurks in shadows, and focuses on hands. It creates this claustrophobic, anxious energy that builds until the bandages finally come off.

And then, the twist.

The Beauty Standards of a Nightmare

When the bandages drop, we see Donna Douglas. She’s stunning. By every 1960s (and 2020s) standard, she is a beautiful woman. But the characters on screen scream in horror. They recoil. Why? Because in this world, "normal" means having sunken eyes, distorted pig-like snouts, and thick, twisted lips.

It’s a masterclass in perspective.

Director Douglas Heyes was incredibly clever with the blocking. He used a technique where the actors playing the medical staff often had their backs to the camera or were shrouded in high-contrast lighting (chiaroscuro). This wasn't just for the sake of the "big reveal." It was meant to dehumanize the "normal" people before we even knew what they looked like. We were forced to empathize with Janet’s muffled voice and her trembling hands. We feel her isolation because the world literally refuses to face her.

Honestly, the makeup for the "pig-people" was pretty advanced for the time. William Tuttle, the legendary MGM makeup artist, handled the prosthetic work. He wanted something that looked biologically functional but aesthetically repellent to a human eye. It worked. Even today, those masks have a creepy, rubbery realism that CGI often misses.

💡 You might also like: Rodrick I’m Sorry Women: The Weird History of a Wimpy Kid Meme

Why Serling Was Obsessed With This Theme

Rod Serling wasn't just writing ghost stories. He was a guy who was deeply frustrated by the censors of the 1950s. He’d try to write about racism or corporate greed, and the networks would gut his scripts to avoid offending sponsors in the South or big-money advertisers.

So, he got smart.

He realized that if he put the same social commentary on a different planet or in a "twilight zone," the censors would let it slide. They saw "The Eye of the Beholder" as a sci-fi gimmick. Serling saw it as a brutal critique of McCarthyism and the pressure to conform to a specific American ideal.

The dialogue in the episode is heavy-handed, but intentionally so. When the Leader speaks on the television screens throughout the hospital, he talks about "glorious conformity" and "the end of the different." It’s terrifying because it’s a speech we’ve heard in different forms throughout history.

It’s about the state deciding what is good.

👉 See also: Theo Von Hot Ones: The Story Behind the Episode Everyone Still Watches

The Production Secrets You Might Have Missed

Interestingly, the episode was originally titled "The Private World of Darkness." A bit clunky, right? "The Eye of the Beholder" is much punchier.

There’s also a weird bit of trivia about the casting. While Donna Douglas played the "unwrapped" Janet Tyler, she didn't provide the voice for the bandaged version. That was actually Maxine Stuart. Stuart performed most of the episode with her head wrapped in real gauze, which meant she had to act entirely through her posture and muffled vocalizations. Douglas was brought in for the final reveal because the producers wanted that specific "Hollywood starlet" look to maximize the shock of her being considered "hideous."

Also, if you look closely at the hospital sets, they’re incredibly sparse. This wasn't just a budget thing—though The Twilight Zone always fought for nickels—it was meant to feel sterile and cold. Like a prison.

The lighting is the real hero here. The use of shadows to hide the doctors' faces for twenty minutes is a feat of choreography. If a single actor turned their head three inches too far to the left, the "makeup twist" would have been spoiled for the home audience. They had to rehearse those movements like a ballet.

What We Get Wrong About the Message

A lot of people think the takeaway is just "beauty is subjective."

That’s the surface level.

📖 Related: Alfred Thaddeus Crane Pennyworth: Why Batman’s Butler is Actually the Scariest Man in DC

But if you dig deeper, the episode is actually about the danger of a majority-ruled morality. The "pig-people" aren't necessarily evil individuals. The doctor actually seems quite pained by his inability to "fix" Janet. He shows her a weird kind of pity. That’s actually scarier than if he were a monster. It suggests that in a society where "different" is "wrong," even the "kind" people will participate in your exile.

They aren't hurting her because they hate her. They're hurting her because they've been taught that her existence is a failure of science and social order.

Janet’s eventual exile to the colony isn't a happy ending, even if she meets a "handsome" man (played by Edson Stroll) who looks like her. It’s a segregation story. It’s a "separate but equal" narrative that Serling was clearly using to mirror the racial tensions of the time.

How to Apply the Lessons of the Twilight Zone Today

We live in an era of filters and algorithmic beauty. In a way, we've built our own version of the surgery room. We have digital tools that pull our faces toward a "mean" or an "ideal" that doesn't actually exist in nature.

If you want to take something away from this 1960 masterpiece, look at how you define "outgroups."

- Audit your "normal." Next time you find yourself judging someone's appearance or lifestyle as "weird," ask if that's your own opinion or a script you've been handed by your "Leader" (or your social feed).

- Value the friction. Janet Tyler was a "failure" because she didn't fit. But she was the only human thing in a room full of prosthetics. The things about you that don't "fit" are usually the only parts of you that are actually real.

- Watch the episode again. But this time, don't look at the pig-people. Look at the doctor’s hands. Look at how much he trembles. Even the people enforcing the "norm" are stressed out by it.

The episode ends with one of Serling's most famous narrations. He reminds us that "beauty is not in the face, but a light in the heart." It’s a bit cheesy, sure. But in a world that’s constantly trying to wrap us in bandages and "fix" us, it’s a reminder we probably need to hear once a week.

Go find a copy of the original 1960 broadcast. Notice the silence. Notice the lack of a jump-scare soundtrack. It doesn't need it. The horror of being told you don't belong is loud enough on its own.

Next Steps for the Fan and Scholar

To truly grasp the impact of this episode, compare it to the 2002 Twilight Zone remake of the same story. While the modern version has a higher budget, notice how it loses the "starkness" of the original. The black-and-white medium was essential to the 1960 version because it stripped away the distractions of color and forced you to focus on shape, shadow, and the raw emotion of the performances. Study the works of Rod Serling further by reading his original teleplays; they often contain stage directions that reveal even more about his disdain for social rigidity. Finally, look into the concept of "The Uncanny Valley" in modern robotics—it’s the scientific bridge to why the "pig-people" makeup still triggers such a deep, visceral response in viewers today.