You’re looking at a tracking screen, maybe at NASA’s website or a third-party app, and you see it. A wavy, undulating line that looks like a snake slithering across a flat map of the Earth. It’s the international space station path, and at first glance, it makes absolutely no sense. If the ISS is orbiting the Earth, shouldn't it just go in a straight circle? Why does it look like it’s wandering around the tropics and then dipping toward the poles?

It's weird.

But there’s a massive logic behind that squiggle. Actually, the ISS is moving in a nearly perfect circle. The "problem"—if you want to call it that—isn't with the space station. It's with our maps. We are trying to take a three-dimensional ball (the Earth) and squash it flat onto a two-dimensional rectangle. When you do that, geometry starts to get messy.

The Geometry of the Squiggle

The International Space Station doesn't orbit directly over the equator. If it did, the international space station path would look like a boring straight line on your map. Instead, it’s tilted. Engineers and scientists call this "orbital inclination." The ISS is inclined at an angle of 51.6 degrees relative to the equator.

Think about why that matters.

If the station stayed over the equator, it would only ever see a tiny strip of the planet. By tilting the orbit, the ISS passes over the vast majority of the populated world. Specifically, it flies over about 90% of the Earth's population. This wasn't an accident. It was a diplomatic and scientific necessity. Because the orbit is tilted, the station spends half its time moving "up" toward the Northern Hemisphere and the other half moving "down" toward the Southern Hemisphere.

When you project that circular motion onto a flat Mercator map, the top and bottom of the circle get stretched out. That’s where the "wave" comes from. It’s essentially a 2D shadow of a 3D circle.

Why 51.6 Degrees?

You might wonder why that specific number was chosen. It wasn't just a random dart throw. It was mostly about Russia. When the ISS was being planned, the partners had to decide where to launch from. Russia’s Baikonur Cosmodrome is located at a high latitude. If the ISS had a lower inclination—say, 28 degrees, which is where NASA launches from Florida—the Russian rockets wouldn't have been able to reach it efficiently.

Launching a rocket is basically like trying to jump onto a moving merry-go-round. You want to jump in the direction the ride is spinning to save energy. By setting the international space station path at 51.6 degrees, both the U.S. and Russia could reach it. It was the "sweet spot" of orbital mechanics and international relations.

The Earth Moves Under Its Feet

If you watch a tracker for a few hours, you’ll notice something even stranger. The squiggle doesn't stay in the same place. Each "loop" of the international space station path is shifted slightly to the west of the previous one.

Why? Because the Earth is spinning.

The ISS is moving fast. Really fast. It clocks in at about 17,500 miles per hour. At that speed, it completes a full trip around the world in roughly 90 minutes. While the station is doing one lap, the Earth beneath it has rotated about 22.5 degrees to the east.

💡 You might also like: NASA New Horizons Probe: Why We Still Can’t Stop Talking About Pluto

So, when the ISS finishes its orbit and comes back to the "top" of its path, the ground it was flying over 90 minutes ago has moved. This is why you can see the ISS from your backyard one night, but you might not see it again for weeks. It’s essentially drawing a giant ball of yarn around the planet, covering different ground with every single pass.

Predicting the International Space Station Path for Your Backyard

Actually seeing the station is a bit of a sport. You can't just look up whenever it's "passing over." It has to be dark where you are, but the ISS has to be high enough to still be catching the sun's rays. It looks like a bright, steady star moving faster than any airplane you’ve ever seen. No blinking lights. No sound. Just a silent, glowing dot hauling across the sky.

If you’re trying to catch it, you need to look at the "ground track." Most people get frustrated because they see the station is "near" them on a map, but they can't see it.

What to Look For

- Elevation: This is how high in the sky it gets. 90 degrees is directly overhead. Anything less than 20 degrees is usually hard to see because of trees or buildings.

- Duration: Most sightings last between 1 and 6 minutes. If it’s only 30 seconds, it’s probably just clipping the horizon.

- Direction: The ISS almost always moves from West to East.

The Precession Factor

Here is a detail that even some space buffs miss: the orbit itself rotates. This is called nodal precession. Because the Earth isn't a perfect sphere—it’s actually a bit fat around the middle due to its rotation—its gravity isn't perfectly uniform. This "equatorial bulge" tugs on the ISS and causes its orbital plane to slowly twist.

Basically, the international space station path is constantly drifting. This is why NASA has to constantly recalculate the "Beta Angle," which determines how much sunlight the station's solar panels get. If the path lines up too perfectly with the "terminator" (the line between day and night), the station can stay in constant sunlight for days. That sounds great for power, but it’s a nightmare for thermal control. The station gets hot. Really hot.

How to Track It Like a Pro

If you want to move beyond just looking at a squiggly line, you should use tools that provide the "State Vector." This is the precise XYZ coordinate of the station in space.

NASA’s "Spot the Station" is the gold standard for beginners. It sends you an email or text when the international space station path is about to bring the lab over your specific zip code. For the more hardcore fans, apps like "ISS Detector" or "Heavens-Above" show you a star map with the exact trajectory plotted against the constellations.

One of the coolest things you can do is check the live feed from the External High Definition Camera (EHDC) on the station. When you see a sunset from that perspective, you're seeing it while moving at 5 miles per second. You get to see a sunrise or sunset every 45 minutes.

Real-World Impact of the Orbit

The specific international space station path dictates everything about life on board. It determines when the crew sleeps (they use UTC/GMT to keep things simple). It determines when cargo ships like the SpaceX Dragon or the Russian Progress can launch. If the "launch window" is missed by even a second, the station has already moved too far along its path, and the rocket has to wait for the Earth to rotate back into the right position.

It also dictates the science. Instruments mounted on the outside of the station, like the ECOSTRESS (which measures plant temperatures) or the NICER telescope (which looks at neutron stars), rely on that specific 51.6-degree tilt to scan the parts of the Earth and sky they need to see.

Actionable Steps for Skywatchers

If you want to see the ISS tonight or this week, don't just wing it.

- Check a reliable tracker: Go to NASA’s Spot the Station website. Enter your city.

- Look for "Max Height": Ignore any passes that are below 40 degrees if you live in a city. You won't see them over the light pollution and buildings.

- Find a dark spot: Even though the ISS is bright (sometimes brighter than Venus), it’s much more impressive when you aren't standing under a streetlamp.

- Use an app with AR: Many apps let you hold your phone up to the sky, and they will draw the international space station path right on your screen so you know exactly where it will appear.

- Watch for the "fade": One of the coolest things is watching the ISS disappear mid-sky. This happens when it enters the Earth’s shadow. It doesn't just blink out; it turns orange or red for a second—just like a sunset—and then vanishes.

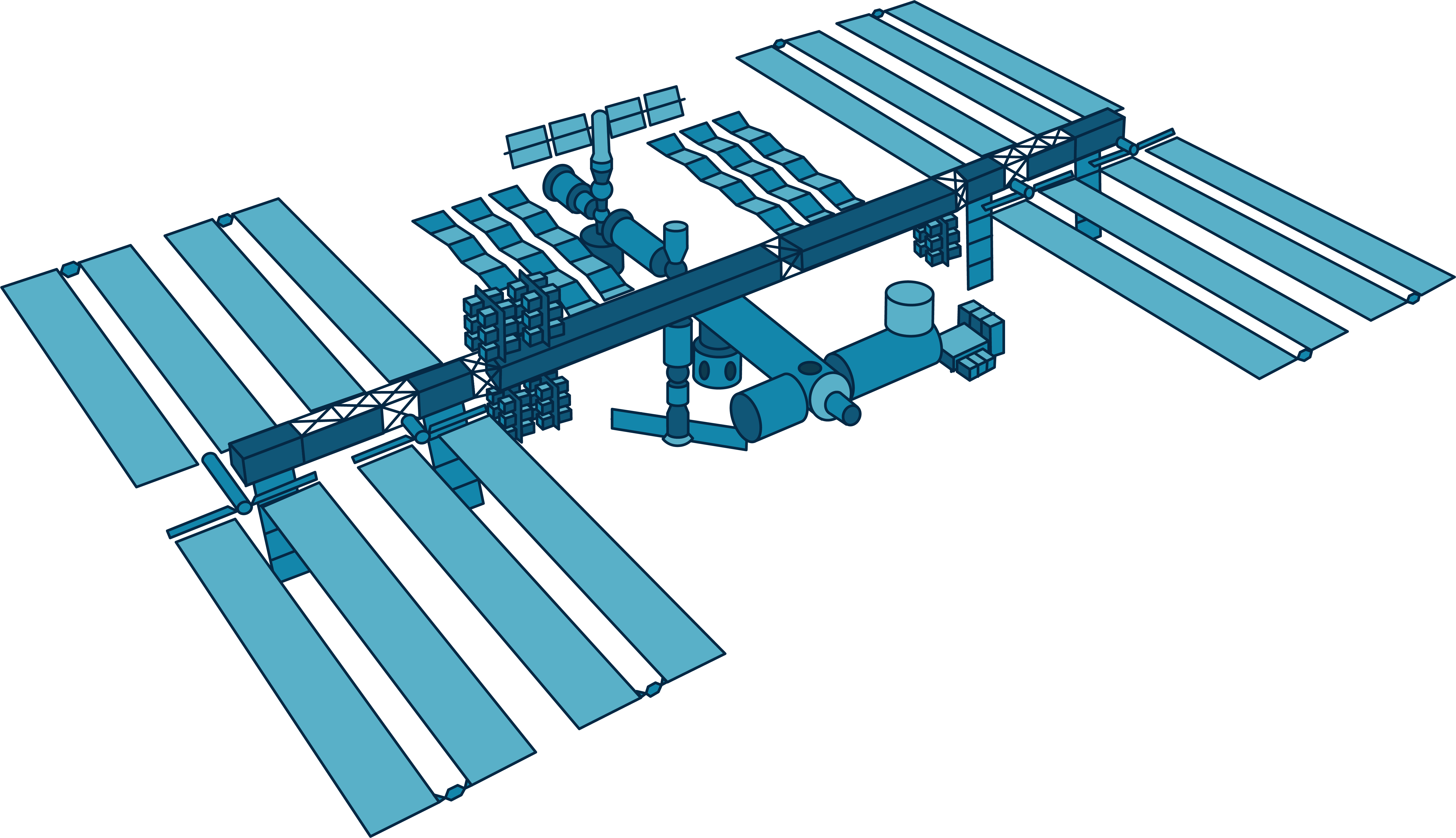

The station has been inhabited continuously since November 2000. Every time you see that light moving across the sky, you’re looking at a football-field-sized laboratory with humans living inside it, orbiting the world at speeds we can barely comprehend. The squiggle on the map might look funny, but it’s the blueprint for one of humanity’s greatest technical achievements.