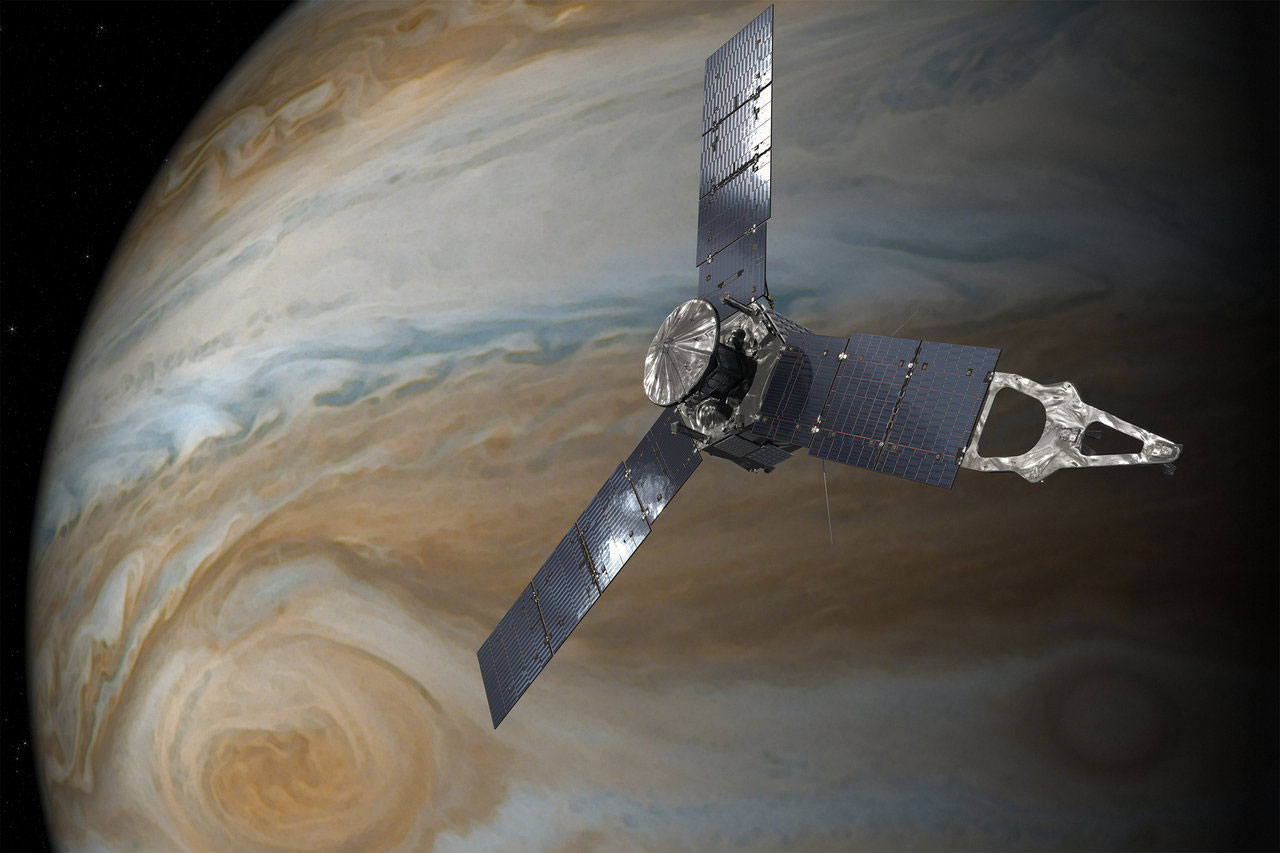

Jupiter is a monster. Honestly, there is no other way to describe it. It's a massive, swirling ball of hydrogen and helium that could swallow 1,300 Earths without breaking a sweat. For a long time, we only saw it from a distance, looking at those pretty tan and red stripes through telescopes or the fleeting flybys of the Voyager probes. But everything changed when the Juno mission at Jupiter actually arrived in 2016. Since then, it’s been hanging out in one of the most hostile environments in the solar system, getting blasted by radiation that would fry your smartphone in seconds, all to tell us what’s actually happening under those clouds.

NASA didn't just build a satellite; they built an armored tank with solar panels.

Most people think of space missions as these delicate, spindly things. Juno is different. It's spinning constantly to stay stable. It's got a titanium vault—literally a box with walls nearly an inch thick—to protect its "brain" from Jupiter's insane magnetic field. If you stood where Juno flies, you’d be exposed to the equivalent of 100 million dental X-rays. It’s wild that it’s still working.

👉 See also: Mac Reset Network Settings: Why Your WiFi is Actually Acting Up

What we finally learned about that "Solid" Core

For decades, planetary scientists like Scott Bolton, the Principal Investigator for Juno, debated what was inside the gas giant. Was there a rocky nugget at the center? Or was it just gas all the way down until it got so dense it turned into liquid?

The data coming back from the Juno mission at Jupiter basically flipped the script.

Instead of a neat, small, rocky core, Juno's gravity measurements suggest a "fuzzy" or dilute core. Imagine taking a solid rock and smashing it into a bowl of oatmeal. It’s a messy, spread-out transition zone that extends out to maybe half of the planet's radius. Why? One leading theory is that a massive protoplanet—something ten times the size of Earth—slammed directly into Jupiter billions of years ago. That impact would have stirred the pot, mixing the heavy elements with the hydrogen and creating the giant, blurry center we see today.

It's messy. It’s confusing. And it makes Jupiter way more interesting than the "perfect" models we had in textbooks back in the 90s.

The Great Red Spot is surprisingly deep

You’ve seen the pictures of the Great Red Spot. It’s that iconic crimson hurricane that’s been screaming across the planet for at least 300 years. But until Juno, we had no clue how deep those roots went. We knew it was wide—big enough to fit Earth inside—but was it just a surface feature?

NASA used Juno’s microwave radiometer to "see" beneath the clouds.

Turns out, the Great Red Spot goes down about 200 to 300 miles (300 to 500 kilometers). To put that in perspective, if this storm were on Earth, it would reach all the way up to the International Space Station. However, the surrounding jet streams—those stripes we see—go even deeper, reaching depths of 1,800 miles.

- The storm is shallow compared to the atmosphere.

- But it’s deep compared to anything we have on Earth.

- The heat at the bottom of the storm might be fueling its longevity.

Those weird geometric cyclones at the poles

Before the Juno mission at Jupiter, we basically ignored the poles because we couldn't see them well. We expected them to look like Saturn’s poles—a nice, neat hexagon.

Nope.

When Juno sent back the first infrared images of Jupiter’s north and south poles, scientists were floored. There are these massive, Earth-sized cyclones huddled together in geometric patterns. At the north pole, there are eight storms surrounding a central one. At the south pole, there are five (and recently a sixth poked its way in). They don't merge. They don't drift away. They just... dance. It’s a stable configuration of chaos that shouldn’t really exist according to traditional fluid dynamics.

The water problem and the "Hot Spots"

One of the biggest goals for the Juno mission at Jupiter was to find out how much water is in the atmosphere. This is a huge deal because water tells us where Jupiter formed. If it has a lot of water, it probably formed further out in the cold parts of the solar system and migrated inward.

The Galileo probe back in 1995 actually dropped a "mini-probe" into the clouds. It found almost no water.

Scientists were confused for twenty years. Was Jupiter dry? Juno finally solved the mystery: Galileo just got unlucky. It dropped its probe into a "hot spot"—basically a desert in the sky where the air is sinking and drying out. Juno’s wider surveys have shown that Jupiter actually has plenty of water, especially around the equator. It’s not a dry wasteland; it’s just incredibly patchy.

Magnetic fields that look like spaghetti

Jupiter’s magnetic field is a monster. It’s the largest structure in the solar system. If you could see it from Earth with your naked eye, it would look twice as big as the full moon.

Juno found that this field is "lumpy."

On Earth, we have a North Pole and a South Pole. Simple. On Jupiter, the magnetic field is irregular. There's a spot near the equator called the "Great Blue Spot" (not actually blue, that's just the color on the map) where the magnetic field is intensely concentrated. It looks like the planet's internal dynamo—the engine making the magnetism—is much closer to the surface than we thought. It's likely driven by "metallic hydrogen," a weird state of matter where hydrogen is squeezed so hard it acts like a liquid metal.

Transitioning to the moons: The Extended Mission

Originally, Juno was supposed to de-orbit and crash into Jupiter in 2018. We didn't want it accidentally hitting Europa and contaminating a moon that might have life. But the spacecraft held up so well that NASA extended the mission.

Now, we’re getting close-ups of the moons.

In the last couple of years, Juno has screamed past Ganymede, Europa, and Io. The images of Io—the most volcanic place in the solar system—are breathtaking. We've seen lava lakes and massive plumes of sulfur.

The Juno mission at Jupiter is now acting as a scout for the upcoming Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission. It’s laying the groundwork by mapping the radiation belts so those future ships know where the "safe" zones are.

Why this actually matters to you

You might wonder why we spend billions of dollars to look at a gas ball 400 million miles away. It’s because Jupiter is the big brother of our solar system. It was the first planet to form. It likely kicked the other planets around, determined where Earth ended up, and probably shielded us from a lot of nasty comets over the eons.

To understand Jupiter is to understand our own origin story.

If Jupiter had formed slightly differently, Earth might be a barren rock or might not exist at all. Juno isn't just taking pretty pictures; it’s doing the forensic work on the birth of our neighborhood.

How to keep up with the Juno mission

The mission isn't over yet. Juno is still orbiting, though its path is changing as Jupiter's gravity tugs on it. It will continue to orbit until late 2025 or even 2026, depending on how the hardware holds up against the brutal radiation.

Next Steps for Space Enthusiasts:

- Check out JunoCam: NASA actually lets the public vote on which features Juno should photograph. You can go to the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) website, download raw data, and process the images yourself. Many of the "official" photos you see on news sites are actually created by amateur citizen scientists.

- Monitor the Io flybys: Juno is currently in its "Io phase." Keep an eye on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) updates for new images of volcanic eruptions.

- Prepare for Europa Clipper: Since Juno is wrapping up its primary moon surveys, now is the time to read up on the Clipper mission, which launches soon to investigate the subsurface ocean of Europa.

- Download a tracker: Use an app like "Eyes on the Solar System" (NASA's web-based tool) to see exactly where Juno is in its orbit right now. It’s pretty wild to see it dive through the radiation belts in real-time.

Jupiter remains a place of extremes. It's beautiful, deadly, and way more complicated than we ever imagined. Thanks to a titanium box and some very smart people in California and Texas, we’re finally starting to get it.