Look at that tiny, pixelated speck. If you squint, you might miss it. It’s smaller than a grain of sand held at arm's length, floating in a vast, dark nothingness. That’s us. Everything you’ve ever known—every war, every first kiss, every boring Tuesday morning—happened on that one-pixel dot.

The picture of earth by voyager 1, famously known as the "Pale Blue Dot," wasn’t even supposed to happen. NASA engineers were actually worried about it. They thought pointing the camera back toward the Sun might fry the sensitive vidicon detectors. It seemed risky. It seemed unnecessary. But Carl Sagan pushed for it. He knew that we needed to see ourselves from the outside, even if we looked insignificant.

The Day the Cameras Turned Around

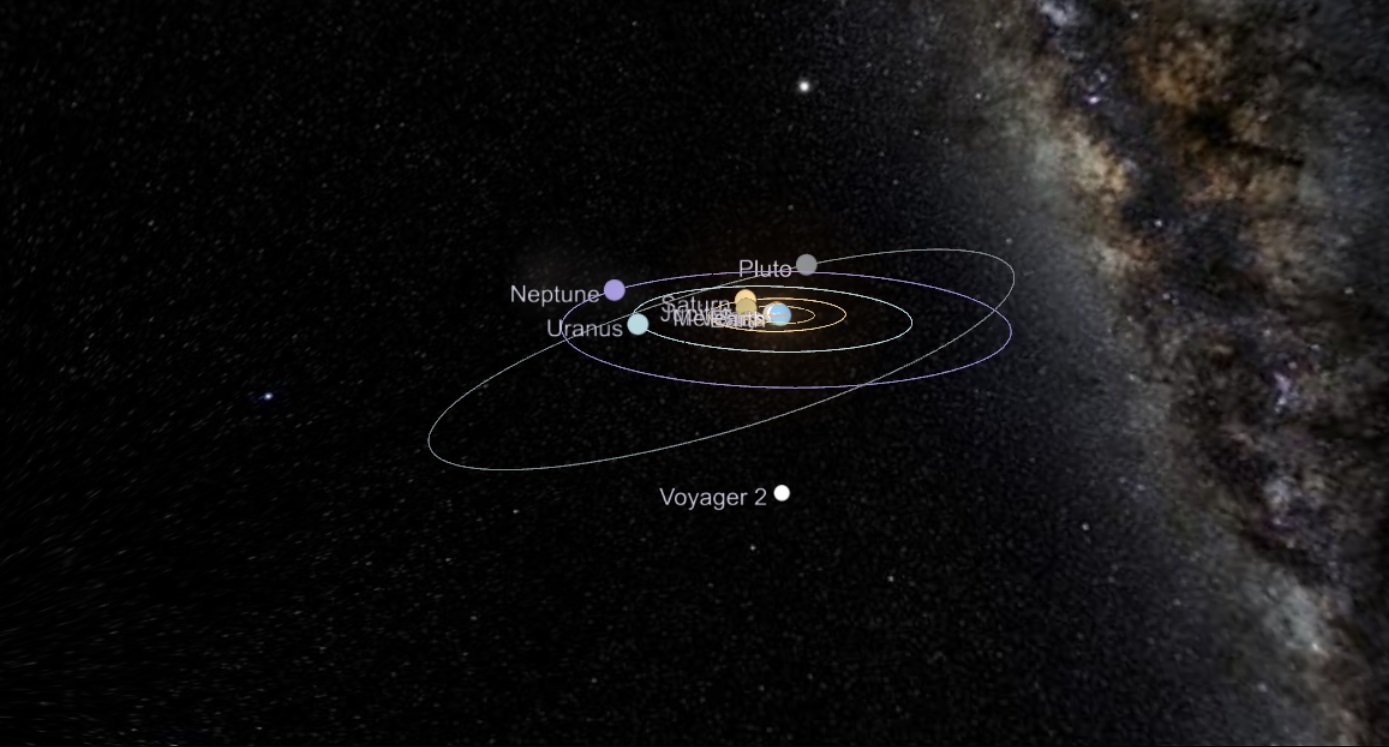

On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 was roughly 3.7 billion miles away. It had already finished its primary mission to Jupiter and Saturn. It was heading out of the solar system forever. Before the cameras were turned off to save power, NASA sent a series of commands to the probe. It turned its neck, snapped 60 frames, and created a "Family Portrait" of our solar system.

The Earth portion of that mosaic is haunting. Because the Earth was so close to the Sun from Voyager's perspective, sunlight scattered across the camera's optics. This created these strange, ethereal beams of light. Earth just happens to be sitting right in the center of one of those rays. It looks like a mistake. Honestly, if a modern AI tried to generate this, it would probably make it look too clean, too "perfect." The real photo is messy, grainy, and heartbreakingly lonely.

Why NASA Almost Said No

The bureaucracy at NASA isn't always keen on "poetic" missions. Candy Hansen-Koharcheck, who worked on the Voyager imaging team, has talked about how they had to weigh the scientific value against the risk to the hardware. Voyager was old. It was cold. It was far away.

Sagan had to lobby the NASA Administrator, Richard Truly, to get the shot approved. He argued that the image wouldn't provide much "science" in the way of data or atmospheric measurements, but its "philosophical value" was immeasurable. He was right. We have high-definition photos of Earth from the International Space Station every day now, but none of them carry the weight of that 1990 image. It’s the difference between a selfie in your bathroom mirror and a photo of your house taken from an airplane. One shows your face; the other shows your context.

It’s Not Just a Photo, It’s a Reality Check

When you look at the picture of earth by voyager, you realize how small our "big" problems actually are. Think about the kings and conquerors who spilled rivers of blood just so they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of that dot. It sounds dramatic because it is.

The technical specs of the camera are almost laughably primitive by today’s standards. We’re talking about an 800x800 pixel fanned-out imaging system. The data took hours to travel back to Earth at a bit rate that would make dial-up look like fiber optic. Each pixel represents a massive amount of space, and yet Earth is less than one single pixel in size ($0.12$ pixel to be exact).

- The Earth is 3.7 billion miles away in the shot.

- The light took about 5.5 hours to reach the spacecraft.

- The image was part of a final sequence before the cameras were shut down for good.

Some people think the "Blue Marble" photo from Apollo 17 is the definitive Earth shot. That one is beautiful, sure. It shows the clouds and the continents. But the Voyager shot is more honest. It shows the vacuum. It shows that there is no help coming from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. It’s just us.

The 2020 Remastering

For the 30th anniversary back in 2020, NASA JPL processed the image again. They used modern image-processing software to clean up the "noise" while staying true to the original data. Kevin Gill, an engineer at JPL, led the effort. The new version is crisper, and the pale blue color of Earth is slightly more distinct against the sunbeams. It didn't change the message, but it made that tiny speck look even more fragile.

I think about the "Overview Effect" often. It’s that cognitive shift astronauts get when they see Earth from orbit. They stop seeing borders and start seeing a biological system. The picture of earth by voyager is the ultimate version of that. You don't just see a lack of borders; you see a lack of presence. The universe is so big that we are effectively invisible.

Technical Hurdles of Deep Space Photography

Taking a photo from 6 billion kilometers away isn't like hitting the shutter on your iPhone. Voyager 1 was moving at about 40,000 miles per hour. The "pointing" had to be precise. If the camera was off by even a fraction of a degree, it would have been staring at empty blackness.

The image was captured through three different filters: violet, blue, and green. When these were recombined on Earth, they produced the color image we see today. The scattering of light that created the "rays" was actually a result of the Sun being so close to the Earth's position in the sky. To the camera, the Sun was still incredibly bright, even from that distance. It’s a bit of a miracle the Earth wasn’t completely washed out by the glare.

📖 Related: DALL-E 3 Image Generator: Why It Still Feels Like Magic (And Where It Struggles)

The Misconceptions

People often think Voyager 1 is the furthest thing humans have ever made. That part is true. But people also think it’s currently taking photos. It’s not. The cameras were turned off shortly after the Family Portrait was taken to save power and memory for the instruments that actually matter now—the ones measuring magnetic fields and plasma. Voyager is currently a "blind" traveler. It feels, but it doesn't see.

Another weird myth is that you can see continents in the Pale Blue Dot. You absolutely cannot. You can barely see Earth. It is a "point source" of light. The blue color comes from the Rayleigh scattering of sunlight in our atmosphere, the same reason our sky looks blue from the ground. We are literally a blue lightbulb in a dark basement.

Why This Matters Today

In 2026, we are more divided than ever. We have social media bubbles and geopolitical tension. We have climate anxiety. Looking at the picture of earth by voyager acts as a reset button for the ego.

There is a certain "cosmic humility" that comes with this perspective. It’s hard to stay angry at your neighbor when you realize you both live on a microscopic dust mote. Sagan’s writing on this remains the gold standard of scientific prose. He called it a "hint of our imagined self-importance." He wasn't trying to be a downer; he was trying to tell us to be kinder to one another.

Actionable Insights: How to Use the "Pale Blue Dot" Perspective

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the news or the general chaos of life, there are actual ways to apply this "Voyager Mindset" to your day-to-day existence.

- Practice the "Zoom Out" Technique: When faced with a stressful situation, mentally visualize yourself from 10 feet up, then 1,000 feet, then from orbit, then from Voyager’s perspective. It usually shrinks the problem down to its actual size.

- Audit Your Priorities: Most of the things we stress about don't matter on a one-year timescale, let alone a cosmic one. Use the image as a visual reminder to focus on what actually sustains life and community.

- Read the Source Material: Don't just look at the photo. Read Carl Sagan’s "Pale Blue Dot" speech. It’s one of the few pieces of 20th-century literature that remains 100% relevant regardless of your political or religious beliefs.

- Support Space Exploration: The only way we get more perspectives like this is by continuing to send "eyes" into the dark. Follow current missions like the James Webb Space Telescope or the upcoming Europa Clipper to stay connected to the "big picture."

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is currently over 15 billion miles away from us. It is entering the true interstellar medium. It carries a Golden Record with our sounds and our music, but its most important gift was probably that one grainy photograph. It told us exactly where we stand. We are small, we are vulnerable, and we are all we’ve got.