You’re standing on the side of a foggy mountain. You can’t see the peak, and you definitely can’t see the base. All you know is that you want to get to the bottom as fast as possible. What do you do? You feel the ground with your boots. You find the direction where the slope feels the steepest under your feet and you take a step that way.

That’s a gradient. Honestly, it’s that simple.

In the world of multivariable calculus and the engines that drive modern AI, the gradient vector is essentially the compass that points you toward the steepest "uphill" climb. If you’re a developer or a student, you've probably seen the symbol $

abla f$. It looks intimidating. It’s not. It’s just a collection of partial derivatives packed into a single arrow.

The Gradient Vector: It’s Just a Directional Arrow

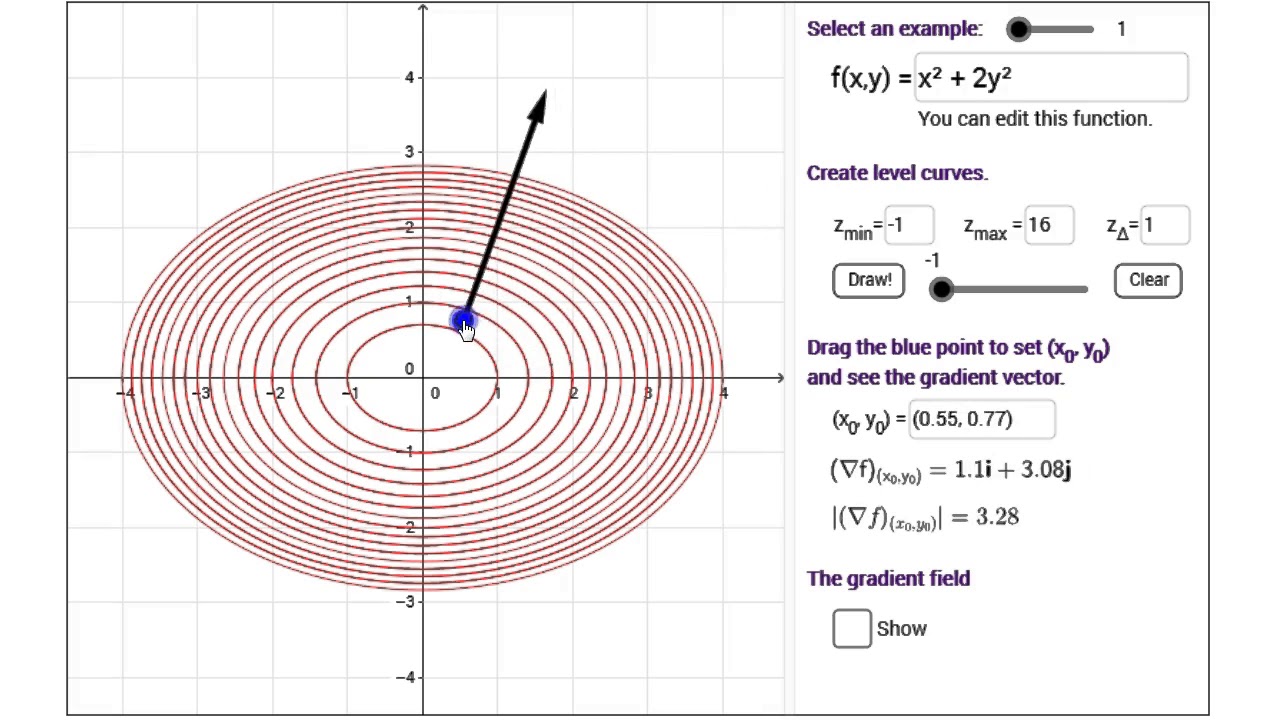

If you have a function—let’s call it $f(x, y)$—it describes a surface. Maybe it’s a heat map of a room or the topographical layout of a valley. The gradient vector at any specific point $(x, y)$ is a vector that tells you two crucial things: which way to move to increase the value of $f$ the fastest, and how steep that increase actually is.

Think of it as a pointer. If you're looking at a weather map and you want to find where the temperature is rising most aggressively, the gradient is your best friend. It doesn't point along the surface; it sits in the input space. If your function depends on $x$ and $y$, the gradient lives in the $xy$-plane.

The formula is straightforward:

$$

abla f = \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \right)$$

It’s just the rate of change in the $x$ direction and the rate of change in the $y$ direction. Together, they create a single force.

Why Everyone Gets the Geometry Wrong

Most people think the gradient points "up" the mountain. While that’s true in a metaphorical sense, the math is more specific. The gradient vector is always perpendicular (orthogonal) to the level curves of a function.

Imagine a map with contour lines. Those lines show where the elevation is the same. If you are standing on a contour line, the fastest way to gain height is to move exactly 90 degrees away from that line. You don't walk along the ridge; you go straight up the face.

This perpendicularity is a foundational rule. James Stewart, whose calculus textbooks have tortured and educated millions, emphasizes this because it’s how we find tangent planes. If you know the gradient, you know the orientation of the entire surface at that point.

The Real-World Engine: Gradient Descent

You can't talk about a gradient vector without talking about how it’s used in Neural Networks. This is where it gets practical. When you train a model—say, a Large Language Model like the ones we use every day—the "loss function" measures how wrong the model is.

We want that "wrongness" to be zero.

Since the gradient points toward the steepest increase, we do the opposite. We move in the direction of the negative gradient. This is Gradient Descent.

It’s a repetitive process.

- Calculate the gradient.

- Take a small step in the opposite direction.

- Repeat until you hit a minimum.

Without the gradient vector, we’d be guessing. We would be throwing random numbers at weights and biases in a trillion-parameter model, hoping something sticks. Instead, the gradient gives us a mathematical "downward" pull. It’s the gravity of data science.

The Nuance: When Gradients Lie

Gradients are local. They only know about the immediate vicinity. This is the "Local Minimum" problem that researchers like Yann LeCun and Geoffrey Hinton have spent decades solving.

✨ Don't miss: Don't Listen to Them ML: Why the Experts Are Often Wrong About Your Models

Sometimes, the gradient leads you into a small dip in the mountain, but there’s a much deeper valley just over the next ridge. The gradient vector doesn't know about that ridge. It only knows that, right here, every direction goes up, so this must be the bottom.

To fix this, we use "momentum." It’s like a heavy ball rolling down a hill; it has enough speed to roll over small bumps (local minima) to find the true bottom (the global minimum).

Breaking Down the Math

If you’re looking at a function $f(x, y, z) = x^2 + \sin(yz)$, the gradient vector is:

$$

abla f = \langle 2x, z\cos(yz), y\cos(yz) \rangle$$

Notice how the $x$-component only cares about $x$. But the $y$ and $z$ components are tangled up. This is why gradients are powerful; they capture the relationship between variables. If you change $y$ just a little bit, it might have a huge impact on the result because of that $z$ multiplier.

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

If you’re working in Python, you aren't usually calculating these by hand. Libraries like PyTorch and TensorFlow do it for you using something called "Autograd" or automatic differentiation.

But you still need to understand the magnitude.

If the magnitude of your gradient vector is near zero, your model has stopped learning. This is the "vanishing gradient" problem. It’s like trying to find the bottom of a hill when the ground is perfectly flat. You’re stuck. On the flip side, if the gradient is too large (exploding gradients), your model will bounce around the valley like a pinball, never actually settling at the bottom.

Understanding the gradient isn't about passing a calculus midterm. It's about knowing how to tune the "learning rate" in a model. The learning rate is just a multiplier for the gradient. A big learning rate means you're taking giant leaps in the direction the gradient suggests. A small one means you're shuffling your feet.

Steps to Master Gradient Intuition

First, visualize level sets. Look at a topographic map and try to draw arrows perpendicular to the lines. That's your gradient field.

Second, play with a simple function in Desmos or a 3D plotter. Look at $z = x^2 + y^2$. The gradient at $(1, 1)$ is $(2, 2)$. It points directly away from the origin because that's the fastest way to get "higher" on the bowl-shaped surface.

Third, apply it to error. In any project, identify your "cost." If you're running a business, your cost might be "customer churn." The gradient would be the combination of factors (price, speed, support) that increase churn the fastest. To save the business, you move in the opposite direction.

The gradient vector is more than a math term; it’s the logic of optimization. Whether you are navigating a mountain in the fog or fine-tuning a multi-billion parameter AI, you are just following the vector.

Stop thinking of it as a formula. Start seeing it as a direction.

Immediate Next Steps for Implementation:

- Audit your Learning Rate: If your loss curve is oscillating wildly, your steps are too large relative to your gradient vector's magnitude.

- Visualize the Manifold: Use tools like Matplotlib to plot the "gradient field" of your loss function to see where the "stagnant" zones are.

- Check for Vanishing Points: If you're building deep networks, use ReLU activation functions to keep the gradient from shrinking to zero as it passes through layers.

- Apply Vector Thinking: In any optimization problem, identify your independent variables and calculate their partial influence to determine your own "steepest" path to improvement.