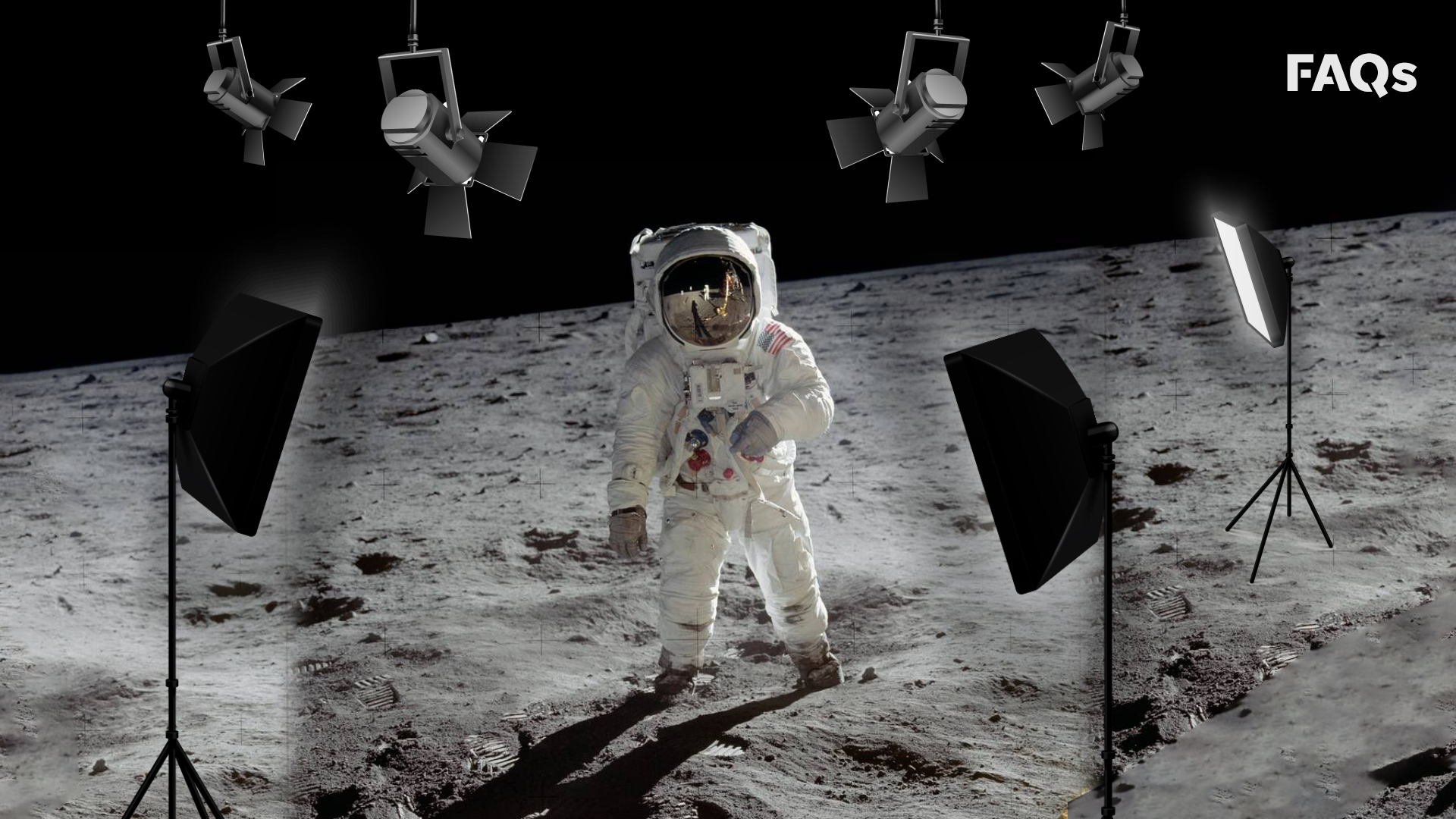

It’s the middle of the night. You’re doom-scrolling, and suddenly you hit a grainy video claiming that Stanley Kubrick directed the whole thing on a soundstage in Nevada. It’s a compelling story, right? The flag ripples when it shouldn't. There are no stars in the photos. The shadows look funky. But when you actually dig into the physics, the logistics, and the sheer scale of the Apollo program, the conspiracy falls apart faster than a cheap suit. Honestly, the reality is way more impressive than any Hollywood hoax could ever be.

Understanding why was the moon landing real isn't just about winning an argument with your uncle at Thanksgiving. It’s about appreciating one of the most insane engineering feats in human history. We’re talking about 400,000 people working together to throw three guys at a rock 238,000 miles away using computers that had less processing power than your modern toaster.

The Cold War was the ultimate fact-checker

Let’s be real for a second. If the United States had faked the 1969 moon landing, who would have been the first person to call them out? The Soviet Union.

We were in the middle of a space race. It wasn't a friendly jog; it was an existential competition for global dominance. The Soviets had their own tracking stations. They were listening. If NASA had just broadcasted a pre-recorded signal from a basement in Houston, the KGB would have known within minutes. They had every incentive in the world to humiliate the U.S. on the global stage. Instead, they sent a congratulatory telegram.

Think about that. The people who hated us most at the time admitted we did it.

Those "missing" stars and "waving" flags

People always point to the photos. "Why can't you see stars?" basically becomes the go-to "gotcha" moment. But any photographer will tell you exactly why: exposure settings. The lunar surface is bright. It’s basically a giant reflector sitting in direct sunlight. If you want to take a clear picture of an astronaut in a white suit standing on a glowing white landscape, you have to set your shutter speed fast. If you kept the shutter open long enough to capture the faint light of distant stars, the astronauts would have looked like glowing blobs of overexposed light.

And the flag? It didn't "wave" because of wind. There’s no air on the moon. NASA knew this, so they designed a flag with a horizontal telescopic crossbar to keep it extended. In the footage, the flag only moves when the astronauts are literally wrestling it into the ground. Once they let go, it vibrates—because there’s no air resistance to stop the motion—and then stays perfectly still.

The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment

If you’re still wondering why was the moon landing real, you can literally prove it yourself tonight if you have a powerful enough laser and a high-end observatory.

The Apollo 11, 14, and 15 crews left behind something called retroreflector arrays. These are basically high-tech mirrors. For over fifty years, scientists at places like the McDonald Observatory in Texas have been bouncing lasers off these mirrors to measure the exact distance between the Earth and the Moon.

You can't bounce a laser off "nothing." Those mirrors are still sitting there in the lunar dust.

842 pounds of evidence

NASA didn't just bring back photos; they brought back rocks. A lot of them. Specifically, 382 kilograms (842 pounds) of lunar material.

These aren't just Earth rocks that look a little weird. Lunar samples have been studied by thousands of scientists from dozens of countries for decades. These rocks have zero water trapped in their crystal structures. They are riddled with tiny "zap pits" from micrometeoroid impacts—something that doesn't happen on Earth because our atmosphere burns those tiny pebbles up.

Geologists like Dr. Farouk El-Baz have spent their lives proving these samples are unique. If they were faked, someone would have noticed a terrestrial signature by now. Instead, we found that the chemical composition of these rocks matches the moon's unique geological history perfectly.

The sheer scale of the secret

Could you keep a secret? Most people can't keep a secret for a week.

Now imagine keeping a secret that involves 400,000 employees. That’s how many people worked on Apollo. We’re talking about janitors, seamstresses who hand-sewed the spacesuits, fuel technicians, and software engineers.

To fake the moon landing, you would need every single one of those people to lie for the rest of their lives. No deathbed confessions. No disgruntled employees leaking documents for a payday. No whistleblowers. In a world where a White House intern can bring down a presidency, the idea that nearly half a million people maintained a perfect conspiracy for fifty years is statistically impossible.

The "It was too hard to go" myth

A common argument is that we didn't have the technology. It’s true, the tech was primitive by our standards. The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) ran at about 1 MHz. Your smartphone is thousands of times faster.

But here’s the kicker: it was actually easier to go to the moon than it was to fake the footage convincingly in 1969.

The way light behaves on the moon is unique. There is only one light source: the sun. This creates perfectly parallel shadows. In a film studio, you use multiple lights, which creates diverging shadows. To recreate those parallel shadows on a soundstage, you would need a wall of millions of tiny lasers or a single light source so powerful and so far away that it didn't exist in 1969.

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Series 10 Charger: What Most People Get Wrong About Fast Charging

Furthermore, look at the dust. When the Lunar Roving Vehicle (the moon buggy) kicks up dust, it follows a perfect parabolic arc and falls immediately to the ground. On Earth, dust clouds linger and float because of air. To fake that in 1969, you would have had to build a massive, several-acre vacuum chamber and suck every molecule of air out of it. We couldn't do that then. We can barely do it now.

Shadow play and perspective

Conspiracy theorists love to point at "non-parallel" shadows in Apollo photos as proof of studio lighting. But it's just basic perspective. If you take a photo of a long road, the lines seem to converge in the distance. If the ground is uneven—which the moon definitely is—shadows will look like they are going in different directions because they are being draped over craters and hills.

Tracking the ghosts of Apollo

In the 2000s, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) started orbiting the moon. It has a high-resolution camera. It has taken photos of the Apollo landing sites from a low altitude.

You can see the descent stages of the Lunar Modules. You can see the tracks left by the moon buggy. You can even see the footpaths where the astronauts walked. These aren't grainy blobs; they are clear, identifiable pieces of hardware exactly where they were left. Unless you think NASA launched a secret mission just to drop props on the moon to cover up a lie from forty years ago, the evidence is pretty definitive.

The Van Allen Radiation Belts

People ask how the astronauts survived the radiation. The Van Allen belts are zones of intense radiation trapped by Earth's magnetic field.

NASA didn't just fly blindly through the thickest part. They calculated a trajectory that skirted the edges of the belts at high speeds. The astronauts spent less than two hours passing through them. Their total radiation dose was about the same as a couple of chest X-rays. It wasn't healthy, sure, but it wasn't a death sentence.

Why it actually matters

The reason why was the moon landing real is because it represents the peak of human capability when resources and will align. If we dismiss it as a hoax, we dismiss the hard work of people like Margaret Hamilton, who led the team that developed the on-board flight software, or the "Hidden Figures" like Katherine Johnson who calculated the trajectories.

It’s easy to be cynical. It’s harder to accept that humans, using slide rules and sheer grit, managed to leave the planet.

How to verify the facts yourself

If you're still on the fence or just want to dive deeper into the technical "how," there are several ways to engage with the evidence directly.

- Visit a Museum: Go to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Look at the Command Module Columbia. Look at the heat shield. You can see the actual scorch marks from re-entry. That kind of damage can't be painted on; it’s the result of hitting the atmosphere at 25,000 miles per hour.

- Read the Source Code: The Apollo 11 guidance computer source code is public on GitHub. Programmers have combed through it for years. It’s a masterpiece of efficiency, designed to handle "restarts" in case of overflow—which actually happened during the landing.

- Study the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Images: You can browse the LRO image gallery online. It’s public data. Look for the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 sites.

- Check the Amateur Radio Records: In 1969, ham radio operators around the world pointed their antennas at the moon and picked up the transmissions. They didn't point them at a secret base in the desert; they pointed them at the moon.

The moon landing wasn't just a TV show. It was a massive, messy, dangerous, and ultimately successful attempt to do the impossible. The evidence isn't just in one photo or one rock—it’s in the thousands of tons of hardware, the millions of pages of documents, and the global scientific consensus that hasn't wavered in over half a century.