It’s a heavy topic. Honestly, it’s one of those things that stops the world in its tracks every single time it happens. When we talk about people that committed suicide, especially those in the public eye, there’s this weird, uncomfortable mix of shock and "I should have seen it coming." But we rarely do. We see the red carpet photos or the sold-out stadium tours and assume everything is fine because, well, why wouldn't it be?

Money doesn't fix your brain.

Take Robin Williams. When the news broke in August 2014, it felt like a collective gut punch. He was the guy who made everyone laugh, the "Genie," the manic energy that seemed bottomless. People couldn't wrap their heads around it. Later, we found out about his struggle with Lewy Body Dementia—a brutal neurological condition—but the initial shock was rooted in the idea that someone so full of "life" could choose to end it. It changed the conversation. It made people realize that depression and terminal illness aren't always visible in a smile.

The Public Fascination and the Reality of Pain

Why do we obsess over this? Part of it is human nature. We want to solve the puzzle. We look for clues in lyrics, old interviews, or social media posts like we’re some kind of amateur detectives trying to find the "why."

But the "why" is usually messy. It’s rarely one single thing.

When Anthony Bourdain died in 2018, it felt different. He had the dream life, right? Traveling the world, eating incredible food, being the coolest guy in the room. His death forced a lot of people to confront the reality that professional success is a terrible shield against mental health struggles. You can be at the top of your game and still feel like you’re drowning.

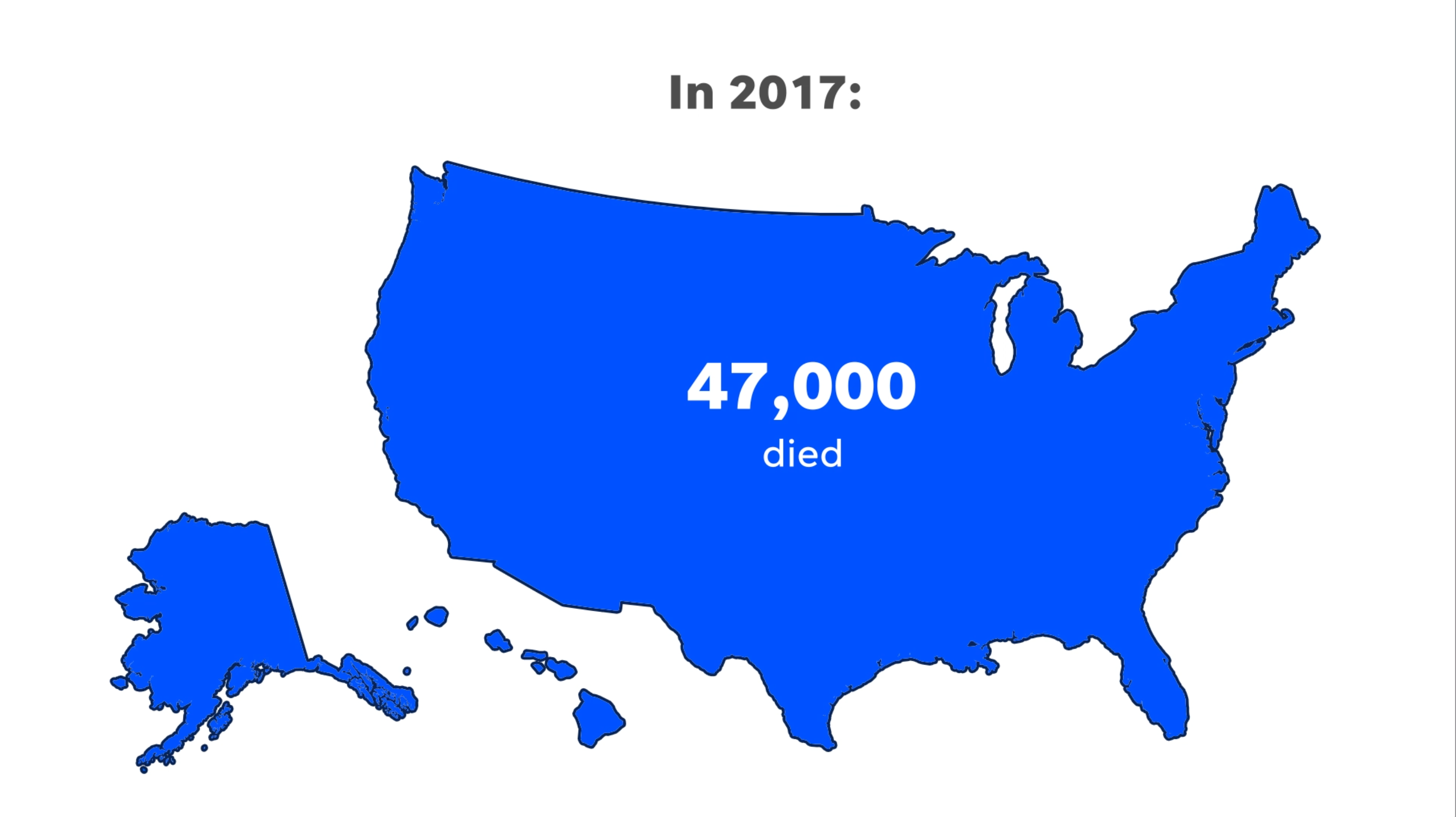

The CDC has reported a steady climb in suicide rates over the last two decades, though there was a slight dip around 2019-2020 before things started trending up again. It’s a public health crisis, not just a celebrity one. But celebrities become the faces of the statistics. They make it real for people who otherwise wouldn't pay attention.

The Ripple Effect

There’s a concept in psychology called the "Werther Effect." Basically, it’s the idea of copycat suicides. It’s named after a 1774 novel by Goethe where the protagonist kills himself, and supposedly, a bunch of young men in Europe did the same.

It’s scary stuff.

This is why organizations like the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) are so strict about how the media reports on people that committed suicide. If you glamorize it, or go into too much detail about the "how," it can actually trigger vulnerable people. It’s a delicate balance between raising awareness and accidentally encouraging more tragedy.

High Stakes and High Pressure

Let’s look at the fashion world for a second. Alexander McQueen. Kate Spade. These were people who built empires.

McQueen was a genius, but he was also deeply lonely and struggling with the death of his mother. He died by his own hand in 2010, just days before her funeral. It’s heart-wrenching. His work was often dark and provocative, and in hindsight, people point to that as a sign. But was it? Or was it just art?

✨ Don't miss: Was John Denver a Christian? What Really Happened with the Legend's Faith

Kate Spade’s death in 2018 was another shocker. She was the queen of bright colors and whimsical handbags. Her brand was literally built on "joy." When her husband, Andy Spade, released a statement later, he mentioned she had been suffering from depression and anxiety for many years. She was actively seeking help. She was taking medication. And yet, it still happened.

It tells us that "getting help" isn't a magic wand. It’s a process. Sometimes the process fails.

The Music Industry’s Heavy Toll

If you grew up in the 90s or early 2000s, the names Kurt Cobain, Chris Cornell, and Chester Bennington carry a lot of weight.

Cobain’s death in 1994 basically defined a generation’s grief. He was the reluctant voice of a movement. His suicide note—which, by the way, shouldn't be picked apart for entertainment—spoke about losing the "fever" for music. He felt like a fraud.

Decades later, Chris Cornell of Soundgarden and Chester Bennington of Linkin Park died within months of each other in 2017. They were close friends. Chester even sang at Chris’s funeral. Their deaths hit the rock community hard because they had both been so open about their demons in their music. You listen to a song like "Numb" or "Black Hole Sun" now, and it hits differently.

It’s a reminder that talent doesn't exempt you from the struggle. If anything, the pressure of maintaining that talent while the world watches can make things worse.

Breaking the Stigma (For Real This Time)

We keep saying "break the stigma," but what does that actually look like?

It looks like not calling suicide "selfish." That’s a big one. When people talk about people that committed suicide, that word pops up a lot. But experts like Dr. Thomas Joiner, who wrote Why People Die by Suicide, argue that it’s not about selfishness. It’s about a "perceived burdensomeness"—the feeling that the world (and your loved ones) would be better off without you.

It’s a glitch in the brain’s survival instinct.

We also need to stop treating mental health like a side project. It’s the main project.

What the Data Actually Says

Most people think they know who is at risk, but the data can be surprising.

- Middle-aged white men actually have the highest suicide rates in the U.S.

- Rural areas often see higher rates than cities, partly due to isolation and lack of access to care.

- Access to lethal means is a huge factor—having a firearm in the home significantly increases the risk during a crisis.

It's not just "tortured artists." It's your neighbor, your coworker, the guy at the hardware store.

What We Can Actually Do

If you're worried about someone, or if you're struggling yourself, the advice is usually "reach out." But that’s hard. It’s really hard.

If you're the one looking in from the outside, don't be afraid to be direct. Asking someone, "Are you thinking about hurting yourself?" doesn't "put the idea in their head." That’s a myth. In fact, it often provides a massive sense of relief for the person who’s been carrying that secret.

Actionable Steps for Support

- Save the number. 988 is the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the US and Canada. It’s not just for people on the ledge; it’s for anyone in emotional distress.

- Remove the means. If someone is in a dark place, help them clear the house of anything dangerous. It creates a "speed bump" that can save a life during a momentary impulse.

- Listen without "fixing." Sometimes people just need to say the dark stuff out loud without being told to "look on the bright side." The bright side feels like a lie when you're in a hole.

- Follow up. The period right after someone leaves a psychiatric hospital or starts a new medication is actually a high-risk time. Don't disappear after the initial crisis.

- Educate yourself on QPR. It stands for Question, Persuade, Refer. It’s like CPR for mental health. Many communities offer free training.

The stories of people that committed suicide aren't just tragedies to be consumed as news. They are warnings. They are reminders that we have no idea what’s happening behind closed doors, or inside someone’s mind.

We lost Naomi Judd in 2022. She was a country music icon. Her daughter, Ashley Judd, has been incredibly brave about speaking out regarding the trauma of finding her mother and the reality of Naomi's long-term depression. She’s pushed for better privacy laws regarding death scenes, but also for more honest conversations about the "disease of the mind."

That’s what it is. A disease.

It’s not a character flaw. It’s not a lack of willpower. And it’s certainly not something that only happens to "other people."

If we want to change the trajectory, we have to keep talking—not just when a celebrity dies, but on the quiet days too. We have to make it okay to not be okay. Because by the time it reaches the point of a headline, it's already too late for one more person.

Next Steps for Awareness and Safety

Check in on that one friend who has been "quiet" lately. Not a text that says "How are you?"—because they'll just say "Fine." Try something more specific, like "I’ve been thinking about you and wanted to see how you're actually holding up." If you are the one struggling, reach out to the 988 lifeline or text HOME to 741741. These services are free, confidential, and available 24/7. Understanding the signs—like giving away possessions, increased substance use, or withdrawing from friends—can be the difference between a tragedy and a recovery.