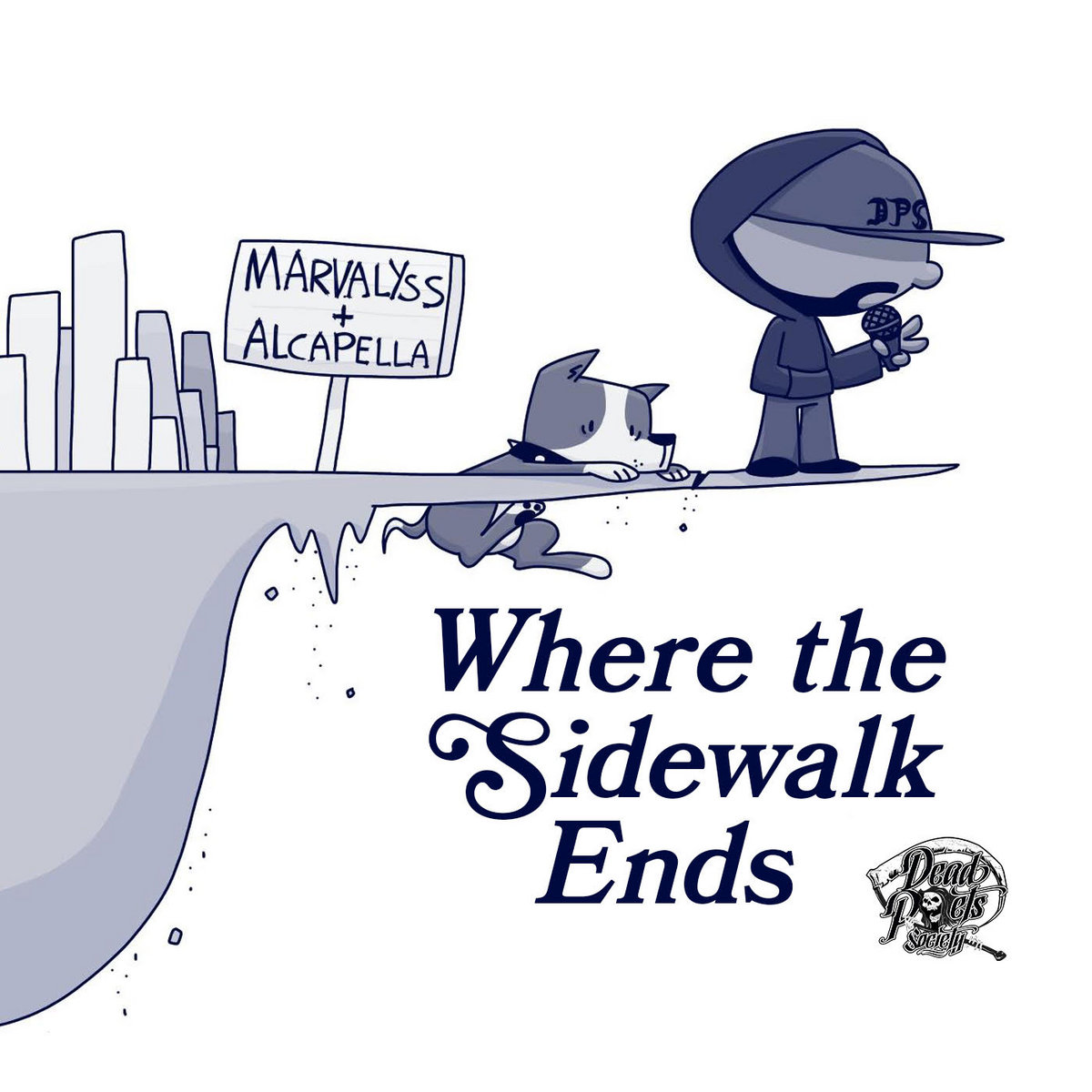

It happened again. You opened the New York Times Games app, sipped your coffee, and stared at a grid of sixteen words that made absolutely zero sense together. Then, you saw it. Tucked between a type of fabric and a random verb was a reference that took you straight back to second grade. If you’ve been searching for where the sidewalk ends nyt clues lately, you aren’t alone. The NYT Connections editor, Wyna Liu, has a specific talent for weaponizing nostalgia to ruin our daily streaks.

Shel Silverstein’s classic poetry collection isn't just a book anymore. It’s a recurring nightmare for word puzzle enthusiasts.

The Where the Sidewalk Ends connection usually pops up in the "Purple" category—the one reserved for the most abstract, "words that follow X" or "words in a title" groupings. It’s tricky because the words themselves—Sidewalk, End, Edge, Path—often fit into three or four other categories simultaneously. That’s the "red herring" strategy that the Times has perfected. One minute you think you’re looking at a category about urban infrastructure, and the next, you realize you’re actually deep in a tribute to 1974 children’s literature.

The Brutal Logic of NYT Connections

Connections is a game of subsets. It looks simple. It isn't.

When where the sidewalk ends nyt becomes the focal point of a puzzle, the difficulty spikes because the book title itself is a phrase. Most players naturally look for synonyms. They see "Sidewalk" and immediately hunt for "Pavement," "Street," or "Curb." But the NYT doesn't always want synonyms. Sometimes, they want you to complete the phrase or identify a shared creator. This is why the game feels more like an IQ test mixed with a trivia night at a bar than a standard word search.

Let's talk about Wyna Liu for a second. As the associate puzzle editor at the Times, she’s become a bit of a cult figure. She understands that our brains are wired to find patterns, so she builds patterns that overlap just enough to be infuriating. If "Where the Sidewalk Ends" is the theme, she might throw in "The Giving Tree" or "A Light in the Attic" just to see if you'll bite on a "Shel Silverstein Books" category. But wait—maybe "Tree" belongs in a category about "Things with Bark," and "Attic" belongs in "Parts of a House."

Honestly, it’s brilliant. It’s also why your group chat is probably full of people complaining about their "One Away" notifications at 8:00 AM.

Why Shel Silverstein is the Perfect Puzzle Subject

Silverstein was a polymath. He wasn't just a poet; he wrote songs like "A Boy Named Sue," drew cartoons for Playboy, and composed screenplays. This vast body of work provides a goldmine for puzzle makers. When you see a hint related to where the sidewalk ends nyt, the puzzle is often testing your ability to categorize a specific era of cultural literacy.

- The "Ending" Hook: Often, "End" is the word that connects everything. The "End of a Sidewalk," the "End of the World," the "End of the Line."

- Visual Cues: Silverstein’s iconic line drawings are so distinct that even seeing a word like "Beard" (think Uncle Shelby's ABZ Book) or "Bandage" can trigger a memory of his sketches.

- The Poetry Connection: Sometimes the category isn't the book, but the type of literature. "Where the Sidewalk Ends" might be grouped with "Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats" or "A Child's Garden of Verses."

The challenge is that the NYT audience is broad. You have Gen Z players who might only know Silverstein from a stray meme and Boomers who read the original 1974 edition to their kids. The puzzle sits right in that sweet spot of universal but specific knowledge.

Navigating the "Red Herring" Minefield

The most common mistake people make when they see a potential where the sidewalk ends nyt connection is committing too early. You see "Sidewalk" and "End" and you click them immediately. Big mistake. Huge.

In the world of professional puzzling, this is known as a "trap." Before you click a single tile, you have to look for the fifth word. If there are five words that seem to fit a category, none of them are safe yet. For instance, if you have "Sidewalk," "End," "Edge," "Border," and "Margin," you have to figure out which one belongs to a completely different group—maybe "Margin" goes with "Profit" and "Spread" in a business category.

Basically, the NYT wants you to be impulsive. The "Submit" button is a lure.

The complexity of these puzzles has actually sparked a massive secondary economy of "Hint" websites. People aren't just looking for the answers; they want to understand the why. They want to know why "Where the Sidewalk Ends" was grouped with "The Twilight Zone" (both are titles involving a physical/metaphorical place).

How to Beat the NYT Games at Their Own Strategy

If you want to stop losing your streak, you have to change how you look at the grid. Stop reading the words. Start categorizing the parts of speech. Is "End" a noun or a verb? If it’s a verb, it means "to finish." If it’s a noun, it’s a "point of termination."

The NYT loves to mix these up. They’ll give you three nouns and one verb that looks like a noun.

Regarding where the sidewalk ends nyt specifically, keep the following literary tropes in mind:

- Titles that start with "Where": Where the Wild Things Are, Where the Red Fern Grows.

- Infrastructure: Sidewalk, Bridge, Tunnel, Overpass.

- Silverstein Classics: The Giving Tree, Falling Up, Runny Babbit.

When you find yourself stuck, try the "Long Press" trick. Most people don't realize that if you just stare at the words without clicking, your brain starts to desaturate the primary meanings and looks for the secondary ones. "Sidewalk" isn't just a place to walk; it's a compound word. Does "Side" or "Walk" fit somewhere else? Could "Side" go with "Order," "Kick," and "Show"?

Probably.

The Cultural Significance of the NYT Word Play

Why do we care this much? It’s just a game. But the where the sidewalk ends nyt phenomenon proves that these puzzles are the new "water cooler" for the digital age. They provide a brief, shared linguistic struggle. In a world of infinite scrolling and AI-generated noise, a curated, human-made puzzle offers a rare moment of intentionality.

Wyna Liu and the NYT team aren't just picking words out of a hat. They are mapping the collective consciousness of their readership. They know we remember the weird, slightly creepy drawings of the guy with the long beard and the bare feet. They know that "The Sidewalk Ends" represents a certain childhood boundary between the known world and the imagination.

🔗 Read more: Getting Borderlands 4 SHiFT Codes Before Everyone Else

That’s why the puzzle feels personal. When you miss it, you don't just feel like you failed a game; you feel like you forgot something you were supposed to know.

Actionable Steps for Tomorrow's Grid

Next time you open the app and suspect a where the sidewalk ends nyt theme or something similar, follow this workflow to save your lives:

- The "Five-Word" Rule: Never submit a category if you can find five words that fit it. One of them is a mole. Identify the mole first.

- Verbs over Nouns: Always check if a word can be used as an action. "End" is the biggest culprit here.

- Say it Out Loud: Many NYT Connections categories are phonetic. "Sidewalk" doesn't have a rhyme, but many of its neighbors might.

- Reverse Engineer the Purple: If you can solve the Yellow (easiest) and Green (straightforward) categories, stop. Don't guess the Blue. Look at the remaining eight words and try to find the "Purple" connection between four of them. This makes the final category a default win.

- Check the Date: The NYT often hides "Easter eggs" related to the date. If it’s Shel Silverstein’s birthday (September 25) or the anniversary of a book's release, the where the sidewalk ends nyt connection isn't a coincidence—it’s a hint.

The sidewalk might end, but the obsession with these puzzles definitely doesn't. Keep your eyes on the grid, watch out for those red herrings, and remember that sometimes a sidewalk is just a sidewalk—but in the New York Times, it's usually a trap.

Next Steps for Success:

Open your "Connections" archive and look for past puzzles featuring literary titles. Practice identifying the "extra" word in groups of five to train your brain to spot red herrings before you burn through your four mistakes. Check the official NYT Gameplay blog for "Wordplay" columns where editors explain the logic behind the most controversial "Purple" categories. This will give you a direct look into the "logic gaps" they like to exploit.