Look at a map. Any map. You see that narrow strip of blue? It’s only about 21 miles at the skinniest point between Dover and Calais. People think they know the map england and france layout because they’ve seen it a thousand times in school or on a flight tracker, but there is so much weirdness happening on those borders that most people just glaze over.

Geography is funny like that.

💡 You might also like: Indonesian Currency to Euro: Why Your Money Feels Like It Disappears (And How to Fix It)

The physical distance is tiny, yet the cultural and cartographic shift is massive. If you’re planning a trip or just trying to win a pub quiz, you have to realize that what you see on a standard Mercator projection isn’t the whole story. For starters, the UK and France are basically leaning into each other, like two people trying to overhear a secret, yet the way we map them often makes them look like isolated blocks.

The Mapping of the English Channel: It's Not Just a Gap

When you pull up a map england and france, your eyes probably go straight to the English Channel—or La Manche if you’re asking the French. They call it "the sleeve" because of its shape. This isn't just a watery void. It’s one of the busiest shipping lanes on the planet.

Every year, over 500 ships crawl through that Dover Strait daily. If you were to map the actual traffic density, the blue water would disappear under a thick rug of red GPS pings. We think of the map as static, but it’s actually a vibrating highway.

Then there’s the Channel Tunnel. It’s the invisible line on the map. It’s about 31 miles long, with 23.5 miles of that being under the seabed. When you’re looking at a map, you should imagine a literal umbilical cord connecting Folkestone to Coquelles. It changed everything for European logistics. Before 1994, the map felt "broken" at the coast. Now, it’s a continuous loop for the Eurostar and freight.

Those Tiny Islands That Confuse Everyone

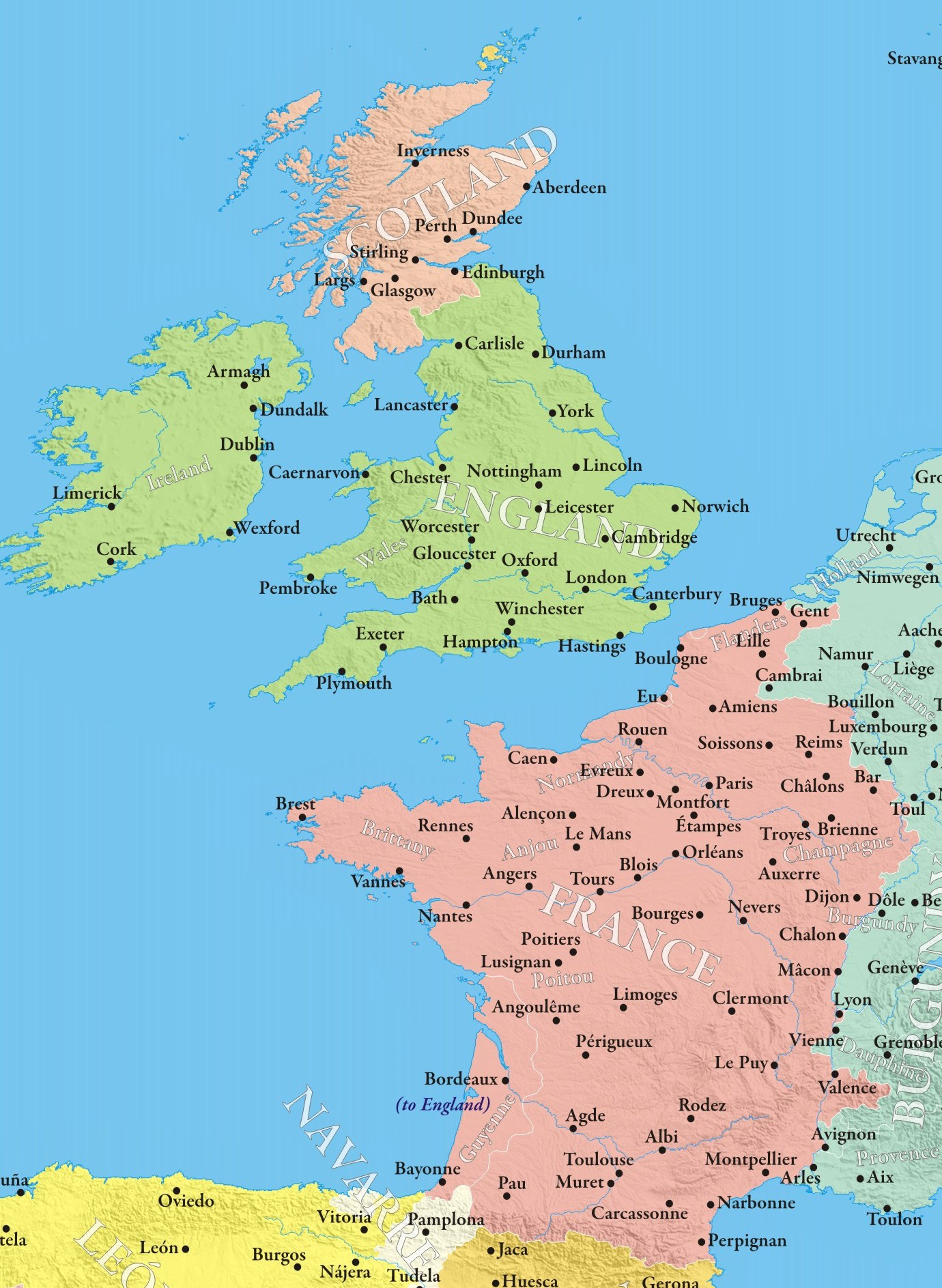

Okay, let’s talk about the Channel Islands. Look at a map of the French coast, specifically near Normandy and Brittany. See those little dots like Jersey and Guernsey? They look like they should be French. They are physically huddled right against the French mainland, sometimes just 12 miles away.

But they aren't French.

They are British Crown Dependencies. This creates a cartographic nightmare for people who like clean borders. You have British-aligned territory sitting deep within what looks like French territorial waters. If you’re navigating these waters, your map needs to be incredibly precise because the tidal range here is one of the highest in the world. In places like Saint-Malo or the Jersey coast, the map literally changes twice a day. The "land" grows and shrinks by miles as the tide goes out.

Why the Map England and France Relationship is Tilted

Most people assume London is north of Paris. And it is. But look closer at the alignment. If you draw a straight line south from London, you don’t hit Paris. You actually end up way west of it, closer to Le Mans. Paris is significantly further east than most casual map-readers realize.

This tilt matters for weather, for flight paths, and for understanding why the sun sets at different times even though the "distance" seems short.

- Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the standard in the UK.

- France is one hour ahead (CET), despite being at almost the exact same longitude.

- This means that when you cross that tiny gap on the map, you’re technically "jumping" through time, even if your physical location hasn't moved much to the east.

It's a political choice, not a geographic one. France decided to stay on Central European Time to be in sync with its neighbors like Germany and Italy. So, the map tells you one thing about proximity, but the clocks tell you another.

The Brittany-Cornwall Mirror Image

If you ever feel like you're seeing double, look at the "toes" of both countries. Cornwall in England and Brittany in France. On a map england and france, they look like mirror images of each other. Both are rugged, granite-filled peninsulas jutting out into the Atlantic.

Even the names are linked. "Brittany" comes from the Britons who fled there from England centuries ago. If you look at a linguistic map, you’d find that the ancient Cornish language and the Breton language are cousins. The map isn't just showing dirt and rocks; it's showing a history of migration that ignored the water entirely.

Cartography and the "Invisible" Borders

Back in the day, mapping these two was a matter of war.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey wasn't just for fun. In the late 1700s, General William Roy started the work that would become the Ordnance Survey. He actually worked with French cartographers, like Cassini, to link the observatories of Greenwich and Paris. They used giant theodolites and lights across the Channel to make sure their maps finally lined up.

Before this, the distance between the two countries was basically a guess. They were literally shouting across the water with lights to measure the world.

Today, we use LiDAR and satellite imagery. We know exactly where the continental shelf drops off. But we still struggle with the "Exclusive Economic Zones" (EEZ). If you look at a modern fishing map of the area, it's a mess of overlapping claims and "grey zones" that have caused real-world tension since Brexit. The map is a battlefield again, just with fishing trawlers instead of warships.

The Scale Problem

One thing that trips people up is the sheer size difference. England is about 50,000 square miles. France is over 210,000. You could fit England into France four times and still have room for a few Belgiums.

When you see them on a map together, the UK often looks "bigger" because it's further north, and certain map projections (like Mercator) stretch things near the poles. In reality, France is a massive landmass—the "Hexagon"—while England is a relatively small, densely populated corner of a much larger island.

Practical Mapping: Getting Around

If you’re actually using a map england and france to plan a trip, stop looking at the whole countries. Zoom in.

The real action is in the "Transmanche" region. This is the area covering the Nord-Pas-de-Calais in France and Kent/Sussex in England. There are regional maps specifically designed for "cross-border" life. People live in Lille and work in London. People in Dover go to Calais for lunch.

- Ferry Routes: Look for the lines between Portsmouth and Caen, or Newhaven and Dieppe. These are often cheaper and more scenic than the tunnel.

- Driving: Remember the map doesn't show you the biggest hurdle—switching sides of the road. The second you roll off that ferry or train, the "map" stays the same, but your brain has to flip.

- Topography: The "White Cliffs of Dover" are famous, but did you know France has them too? Cap Blanc-Nez is the French side of the same geological formation. It’s the same chalk. The map shows a break, but the geology shows it’s all one piece of land that just happened to get flooded when the ice caps melted 8,000 years ago.

The Doggerland Factor

Wait, let's go back 8,000 years. If you were looking at a map england and france back then, there was no water.

✨ Don't miss: Jesse Brewer Jr Park: What Most People Get Wrong

There was a massive land bridge called Doggerland. You could walk from London to Paris without getting your feet wet. You could walk to Denmark. When the Storrega Slide (a massive underwater landslide) happened and sea levels rose, the "map" we know today was born.

Thinking about this makes you realize how temporary these borders are. The North Sea and the Channel are relatively shallow. If the sea level dropped by just 100 meters, the map would revert, and England and France would be one continuous landmass again.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Look at the Map

Don't just stare at the screen. Use the map to actually understand the logistics of the region.

First, check the ferry ports beyond the "Short Sea" (Dover/Calais). If you’re heading to Western France (Brittany or the Loire Valley), mapping a route from Plymouth or Portsmouth saves you hours of driving on the other side.

Second, look at the rail maps. The LGV (Ligne à Grande Vitesse) in France is a different beast than the UK rail network. You can get from London to Marseille in about 6.5 hours. That’s a huge distance on the map, covered in a fraction of the time you’d expect.

Third, pay attention to the "empty" spaces. The map of England is cluttered. High population density everywhere. Once you cross into France and look at the map of the "Diagonal of Emptiness" (la diagonale du vide), you see huge swaths of land with almost no one in them.

Fourth, use nautical charts if you're curious about the "real" border. Territorial waters extend 12 nautical miles from the coast. In the Dover Strait, where the gap is only 18 nautical miles, the countries have to split the difference. There is a literal line in the water that coast guards monitor.

💡 You might also like: Whistler Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About January

Final Mapping Tips

- Offline Maps: If you're traveling between the two, download Google Maps for the entire northern coast of France and southern coast of England. Signal can get spotty when you're transitioning between international towers on a boat or train.

- Check the Tides: If you're visiting places like Mont Saint-Michel or the islands off the coast of Jersey, the map is a lie. The "land" disappears. Always check a local tide table.

- Scale Matters: Don't underestimate the drive from Calais to the south of France. It looks like a "quick trip" on a map of Europe, but it's a solid 10-hour slog.

The map england and france is more than just two shapes on a screen. It's a record of rising seas, ancient wars, and modern high-speed engineering. Next time you see that blue gap, remember that it’s both a barrier and a bridge.

To get the most out of your geographic research, try looking at topographic maps rather than just political ones. You'll start to see the shared ridges and valleys that ignore the flags and the fences. Look at the seabed maps, too. They reveal a hidden world of valleys and plains that used to be home to humans before the water took over.

Essentially, don't trust the first map you see. Zoom in, look at the layers, and realize that England and France are a lot closer—historically, geologically, and literally—than a simple 2D drawing suggests.