You’re probably looking at a blue-and-green blob on your phone right now. It looks official. It’s pulsing, maybe it’s even got a little play button that shows a storm sweeping across the Midwest or a typhoon swirling near Japan. But here’s the thing: most people using a world weather map live don't realize they aren't looking at "live" data at all. They’re looking at a guess. A very educated, multi-billion-dollar guess, sure, but a guess nonetheless.

Weather data is messy. It’s chaotic. It involves thousands of floating buoys, high-altitude balloons called radiosondes, and satellites like the GOES-R series that sit 22,000 miles above the dirt. When you open a live map, you’re seeing the intersection of massive computing power and raw, terrifying nature. But if you don't know which layer you’re looking at—radar versus satellite versus model—you’re basically reading a map in a language you don't speak.

The Illusion of "Live" and the Reality of Latency

Let's get real for a second. Nothing is truly "live" when it involves a signal traveling from a storm cell to a ground station, then to a server in Virginia, and finally to your smartphone.

When you check a world weather map live, you’re usually seeing radar data that is 5 to 10 minutes old. In a tornadic supercell moving at 60 mph, that 10-minute delay means the "hook echo" you see on your screen is actually a mile or two down the road from where the map says it is. That's a huge gap if you're trying to stay safe.

Satellites are a different story. True global maps rely on "mosaics." This is where developers stitch together data from different sources like the Himawari-8 over Asia and Meteosat over Europe. It’s a Frankenstein’s monster of data points. Sometimes the edges don't line up perfectly. You might see a cloud suddenly vanish at a certain longitude. That’s not a glitch in the atmosphere; it’s just where one satellite’s "eyes" end and another’s begin.

✨ Don't miss: Facebook Political Ads: Why They Are Still Smarter and Messier Than You Think

Radar vs. Satellite: Know the Difference or Get Soaked

Radar is active. It sends out a beam, hits a raindrop, and bounces back. It’s great for local detail. But radar has a range limit. It can’t see over mountains well (that's called beam blockage), and it definitely can't see over the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Satellite data is passive. It just sits there and records what’s happening. Infrared satellite maps are the ones that look like heat signatures. They aren't measuring rain; they're measuring the temperature of cloud tops. If the cloud top is freezing cold, it’s very high up, which usually means a massive thunderstorm is brewing. If you’re looking at a world weather map live and see bright red or purple blobs over the ocean, you’re looking at cold air high in the sky, not necessarily a flood on the ground.

Why Your Phone App and the Local News Disagree

Ever notice how Apple Weather says it's raining but the radar looks clear? Or vice-versa?

It’s all about the models. Most "live" maps use something called the GFS (Global Forecast System) or the ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts). The European model is generally considered the "king" of accuracy, especially for hurricanes. It’s run on some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world in Bologna, Italy.

📖 Related: Latest Hubble Telescope Pictures: Why This 35-Year-Old Legend Still Wins

However, many free apps use the GFS because the data is free from NOAA. The GFS is incredible, but it has a habit of being a bit "excitable" with big storms. It might show a blizzard ten days out that never happens.

Then there are High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) models. These are the "live-ish" ones. They update every single hour. If you want to know if it's going to rain on your BBQ in two hours, stop looking at the 10-day forecast and find a map that displays the HRRR layer. It’s a game changer.

The Tech Behind the Beauty

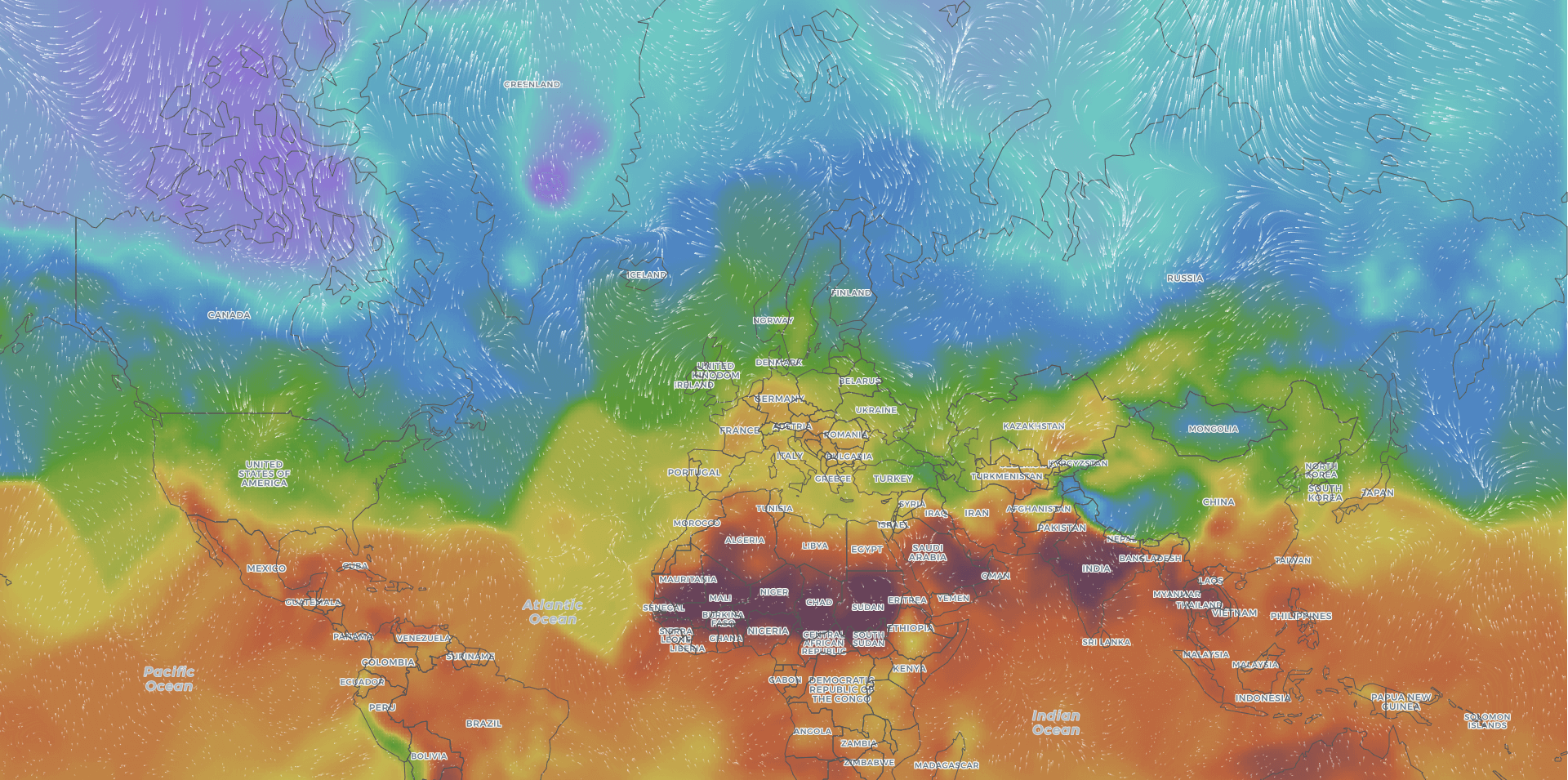

The visuals we see now are insane compared to ten years ago. Websites like Windy.com or Ventusky have turned meteorological data into high-art. They use "particle animation" to show wind flow.

Those flowing white lines? They’re basically just math. The computer takes wind speed and direction data points and connects the dots with moving tracers. It makes a world weather map live feel alive, but remember, those lines are a visualization of a data field, not individual gusts of wind being tracked by a camera.

👉 See also: Zenith TV Remote Control: Why These Vintage Clickers Are Still Kicking Around

The Role of AI in 2026

Honestly, AI has changed everything about how these maps function. Companies like Google (with GraphCast) and NVIDIA are now producing weather models that can run on a desktop computer in seconds, whereas the old-school models took hours on a supercomputer.

This means the "live" part of the map is getting faster. We’re moving toward "nowcasting," where the AI looks at the last three hours of radar and predicts exactly where the rain will be in 15 minutes with terrifying precision. It’s not perfect, but it’s getting harder to catch the machines in a lie.

How to Read a Weather Map Like a Pro

If you want to actually use a world weather map live without getting confused, you need to look at the pressure lines—the isobars.

- Tight lines: If the lines are packed close together like a topographical map of a steep mountain, it’s going to be windy. Very windy.

- The "L" and "H": Low pressure (L) usually means "Lousy" weather. Air is rising, cooling, and condensing into rain. High pressure (H) means "Happy" weather. Air is sinking, which prevents clouds from forming.

- The Blue Spikes and Red Semicircles: These are fronts. A cold front (blue spikes) acts like a snowplow. It pushes under the warm air and kicks up storms. If you see those spikes heading your way on a live map, expect a sudden temperature drop and a quick, violent burst of rain.

Don't Ignore the Dew Point

Temperature is a liar. A 90-degree day in Vegas is fine. A 90-degree day in New Orleans is a death march. When you’re looking at your weather map, toggle the "Dew Point" layer.

If the dew point is over 70, it doesn't matter what the temperature says—you’re going to be miserable. If it’s over 75, you’re in "tropical soup" territory where storms can explode out of nowhere because there’s so much fuel (moisture) in the air.

The Limitations of Global Coverage

We have huge "blind spots." The ocean is the biggest one. While we have satellites, we don't have enough physical sensors on the water. This is why hurricane intensity is so hard to predict. We know where the storm is, but we don't always know exactly how fast the wind is blowing at the surface unless a "Hurricane Hunter" plane flies directly into the eye.

Similarly, in parts of Africa and South America, ground-based radar is sparse. If you look at a world weather map live for those regions, you’re seeing mostly satellite estimates. It’s a "best guess" based on cloud brightness. It’s impressive technology, but it’s not the same as the high-density NEXRAD radar coverage we have in the US or Europe.

Actionable Steps for Better Tracking

Stop relying on the pre-installed weather app on your phone for anything serious. It’s usually a simplified version of a secondary model.

- Get a Pro-Level Viewer: Download an app like RadarScope or use Windy.com. These allow you to see the raw data, not the "cleaned up" version.

- Check the Timestamp: Always look at the bottom corner of your world weather map live. If it says "14:15Z," that’s Zulu time (UTC). You need to convert that to your local time to see how old the data actually is.

- Look at "Vorticity": If you’re a real weather geek, look for the vorticity layer. It shows the "spin" in the atmosphere. High vorticity usually means a storm system is strengthening.

- Compare Two Models: If the GFS shows a storm and the European (ECMWF) doesn't, don't buy the milk and bread yet. Wait for "model agreement." When they both start showing the same thing, that’s when you should actually worry.

- Use Webcam Layers: Many live maps now let you toggle on traffic or weather cameras. If the radar says it’s pouring rain but the live camera 10 miles away shows dry pavement, the storm might be elevated—meaning it’s raining in the sky but evaporating before it hits the ground (a phenomenon called virga).

Weather is the ultimate chaotic system. A butterfly in Brazil might not actually cause a tornado in Texas, but the math behind weather prediction is just as delicate. By understanding that your world weather map live is a mix of delayed radar, satellite imagery, and AI-driven models, you can stop being a victim of the forecast and start reading the sky for yourself.