You’ve seen the images. A ghostly white hand, a jagged break in a tibia, or maybe that grainy airport security scan of your carry-on. We all know what they do, but most people treat x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum like some kind of magic camera flash. It isn't magic. It's actually a violent, high-energy event that happens at the atomic level, sitting in a very specific, very crowded neighborhood between ultraviolet light and gamma rays.

Honestly, the way we teach the spectrum in school is kinda misleading. We see those neat little rainbow charts where everything has its own tidy box. In reality, the spectrum is a messy, overlapping continuum. X-rays are the middle children of the high-energy world. They have enough "oomph" to punch through your skin, but they aren't quite the world-ending monsters that gamma rays can be.

Wilhelm Röntgen stumbled onto them in 1895 while messing around with a vacuum tube in his lab. He noticed a screen across the room started glowing, even though his tube was covered in black cardboard. He called them "X" rays because he had no clue what they were. Today, we know exactly what they are: photons with wavelengths roughly between 0.01 and 10 nanometers. To put that in perspective, an X-ray wavelength is about the size of an atom.

Where X-rays Actually Sit and Why the "Gap" Matters

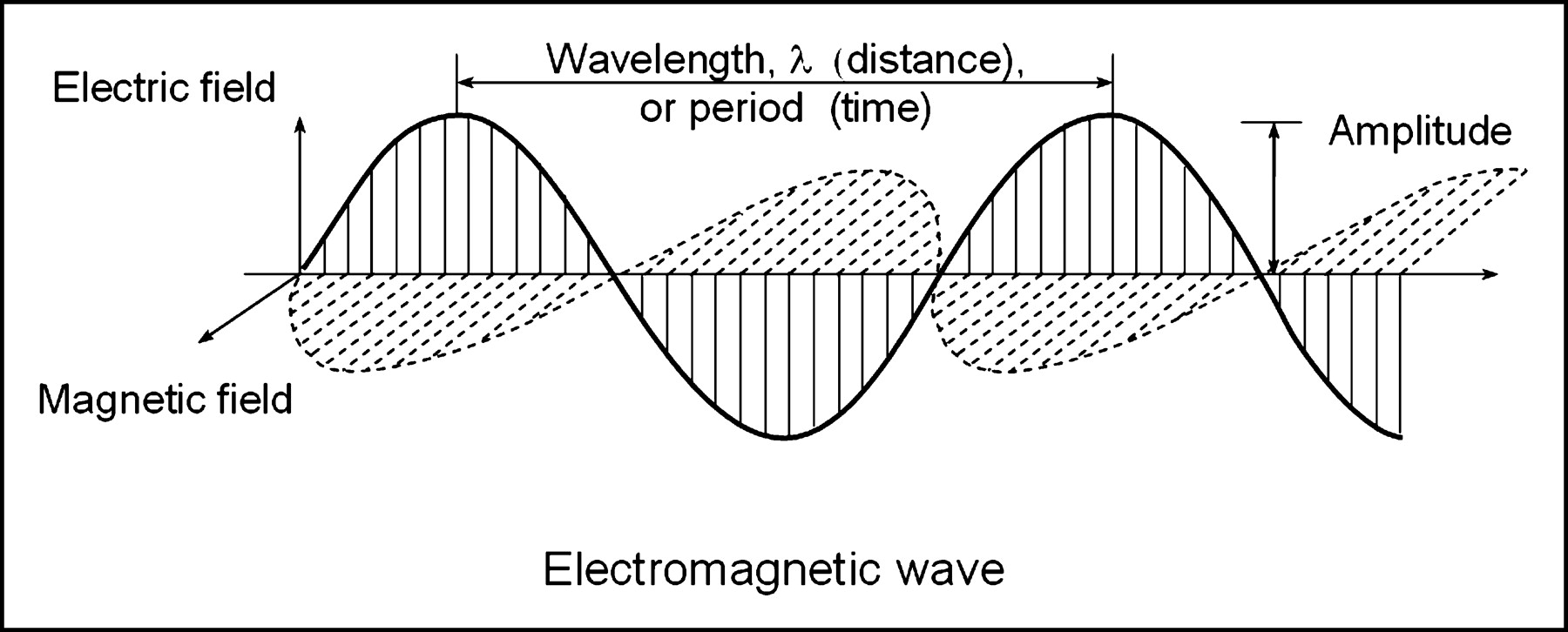

When we talk about x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum, we have to talk about energy. Light is basically just a delivery service for energy. The shorter the wavelength, the more "packetized" energy a photon carries. X-rays are high-frequency, short-wavelength radiation. They exist in a range where they stop acting like waves (the way radio waves do) and start acting more like little bullets (particles).

🔗 Read more: Uses for Neon: It Is Way More Than Just Gas for Dive Bar Signs

Physicists usually split them into two camps: "soft" X-rays and "hard" X-rays. Soft X-rays have longer wavelengths and lower energy; they’re the ones that get absorbed by things like air or thin biological tissue. Hard X-rays are the heavy hitters used in industrial NDT (non-destructive testing) to look for cracks in jet engines. They have frequencies reaching up to $10^{19}$ Hz.

The Ionization Problem

This is where things get serious. Because X-rays carry so much energy, they are "ionizing." This means when an X-ray hits an atom, it doesn't just bounce off or warm it up like microwave radiation does. It has enough kinetic energy to rip electrons straight out of their orbits.

This creates ions. In a piece of steel, that’s no big deal. In your DNA? That’s a potential mutation. This is why the technician leaves the room or hides behind a lead shield while you’re getting your teeth checked. Lead is incredibly dense—its atoms are packed so tightly and have so many electrons that the X-ray photons essentially get "lost" in the crowd and can't make it through to the other side.

How We Actually Make These Things

You can't just flip a switch and get an X-ray like you do with a LED bulb. Generating x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum requires a brutal process called Bremsstrahlung. That’s a German word meaning "braking radiation."

Basically, you take a bunch of electrons, accelerate them to ridiculous speeds using high voltage, and then slam them into a metal target—usually tungsten. When those electrons hit the tungsten atoms, they stop or change direction so fast that they "scream" out energy in the form of X-rays.

It's incredibly inefficient. About 99% of the energy used in an X-ray tube turns into heat. Only 1% actually becomes the X-rays we use for imaging. This is why X-ray machines need massive cooling systems; if they didn't, the tungsten would literally melt into a puddle within seconds.

Beyond the Hospital: X-ray Astronomy

We often forget that the universe is screaming in X-rays. Earth’s atmosphere is great at blocking them—which is lucky for our skin—but it's annoying for scientists. To see x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum coming from space, we have to put telescopes in orbit.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is the gold standard here. It looks at black hole accretion disks and supernova remnants. These are places where matter is being heated to millions of degrees. When gas gets that hot, it stops glowing in visible light and starts blasting out X-rays. If you only looked at the sky with your eyes, you’d miss the most violent, interesting parts of the cosmos.

✨ Don't miss: That Wild Jet Powered Smart Car: Why Bill Berg’s 220 MPH Custom Build Still Breaks the Internet

The Modern Tech You Didn't Realize Uses X-rays

It isn't just about broken bones anymore. The technology has evolved into something called "Backscatter" and "CT" (Computed Tomography).

- CT Scans: Instead of one flat picture, a CT scanner spins an X-ray source around you 360 degrees. It takes thousands of "slices" and a computer stitches them into a 3D model. It’s like looking at a loaf of bread by taking a picture of every individual slice.

- Lithography: In the world of microchips, we are hitting a wall. We can't use visible light to "print" circuits anymore because light waves are too fat. We need the tiny, tiny wavelengths of X-rays to etch patterns onto silicon that are only a few nanometers wide. Without X-rays, your smartphone would be the size of a brick.

- Art Authentication: Curators use X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to see what’s under a painting. They can identify the chemical signature of the pigments. If a "17th-century" painting has titanium white—a pigment not invented until the 20th century—the X-rays will catch the fraud instantly.

Why We Should Stop Being Terrified of Them

There is a lot of "radiophobia" out there. People hear "radiation" and think Chernobyl. But context matters. The dosage of x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum you get from a standard chest X-ray is about 0.1 mSv.

For comparison, you get more radiation than that just by living at a high altitude for a year (cosmic rays) or by eating a lot of bananas (which contain radioactive potassium-40). The risk is cumulative, sure, but for a one-off diagnostic tool, the benefit of seeing a tumor or a fracture far outweighs the microscopic risk of cellular damage.

The real danger is in prolonged, unprotected exposure, which is why the history of X-rays is littered with "Radium Girls" and early researchers who lost fingers because they didn't realize these invisible rays were cooking their tissues at a microscopic level.

Looking Ahead: Phase-Contrast Imaging

The future of x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum isn't just about "shadows." Traditional X-rays rely on absorption—dense stuff blocks the light. But new "Phase-Contrast" imaging looks at how X-rays bend (refract) as they pass through tissue.

This is huge because it allows us to see soft tissues—like lungs, brains, and cartilage—with the same clarity we currently get for bones. It could mean catching cancers years earlier than we do now, without needing invasive biopsies.

Actionable Insights for the Next Time You're at the Doctor

If you're heading in for imaging, here is how to handle it like an expert:

- Ask for the "Thyroid Shield": If you’re getting dental X-rays or an extremity scan, ask for a lead thyroid collar. Your thyroid is one of the most radiation-sensitive parts of your body.

- Keep a Digital Log: Don't rely on your doctor's office to keep your history forever. Keep a folder of when you had scans. It helps avoid "double-scanning" if you switch doctors, which reduces your lifetime cumulative dose.

- Understand the "ALARA" Principle: This stands for "As Low As Reasonably Achievable." It’s the gold standard for radiologists. If a doctor orders a scan, ask if it’s the lowest dose method available to get the necessary information.

- Check for Digital Radiography: Older film-based X-rays require higher doses of radiation to get a clear image. Modern digital sensors are much more sensitive, meaning they need a shorter "burst" to get the same quality picture. Most modern clinics use digital, but it’s always worth asking if you’re concerned about exposure.

X-rays aren't just a tool for the ER; they are a fundamental part of how we understand the very small and the very large. From the atoms in your phone's processor to the black holes at the center of our galaxy, x-rays in the electromagnetic spectrum provide the "high-energy eyes" we need to see the invisible world.