Zinc is weird. It’s one of those metals we take for granted because it’s basically everywhere—from the pennies in your pocket (well, the core of them, anyway) to the "galvanized" steel buckets at the hardware store. But if you’ve ever tried to melt it in a backyard foundry or studied it for a metallurgy project, you know it doesn't behave quite like copper or iron.

The zinc melting point is exactly 419.5 °C, which translates to about 787.2 °F.

That is actually quite low for a structural metal. To put that in perspective, iron doesn't even think about turning into a liquid until it hits 1,538 °C. Zinc is a bit of a lightweight in the heat department. It melts so easily that you can actually liquefy it on a standard kitchen stove if you have the right crucible, though I definitely wouldn't recommend doing that because of the fumes. Seriously. Zinc shakes off its solid form faster than almost any other common transition metal except for cadmium or lead.

Why the melting temperature of zinc matters for industry

Why do we care about these specific 419.5 degrees? Because it makes zinc the king of die casting.

In manufacturing, die casting is basically the process of forcing molten metal into a mold. Since the melting temperature of zinc is so low, it doesn't eat through the steel molds (dies) nearly as fast as other metals would. You save a fortune on equipment maintenance. If you were trying to die-cast something with a higher melting point, like brass, your molds would warp and degrade in no time. Zinc just flows right in, cools down, and pops out with incredible detail. It's why your car's door handles, those tiny gears in your clock, and even some high-end bathroom fixtures are made from zinc alloys like Zamak.

But there is a catch.

Zinc has a "boiling point" that is surprisingly close to its melting point compared to other metals. It boils at 907 °C (1,665 °F). While that sounds like a huge gap, in the world of industrial furnaces, it’s a narrow window. If you overheat zinc just a little bit too much, it starts to vaporize. This creates zinc oxide fumes—white, fluffy clouds that look like "philosopher's wool" but act like a poison. If you breathe that stuff in, you get "metal fume fever." It feels like the worst flu you’ve ever had, complete with chills and body aches. Old-timers in the foundry world call it "the zinc shakes."

The science behind the 419.5 °C mark

At a molecular level, zinc is a bit of an oddball. It sits in Group 12 of the periodic table. Most metals are packed together in a way that makes their bonds incredibly strong, requiring massive amounts of energy (heat) to break. Zinc has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure, but it’s "distorted."

The atoms are slightly further apart in one direction than the others.

Because the bonds aren't perfectly symmetrical or overwhelmingly strong, it takes less thermal energy to agitate those atoms enough to break them out of their rigid lattice. That’s your melting point right there. It’s the moment the thermal vibrations overcome the metallic bonding holding the HCP structure together.

Alloys change the game

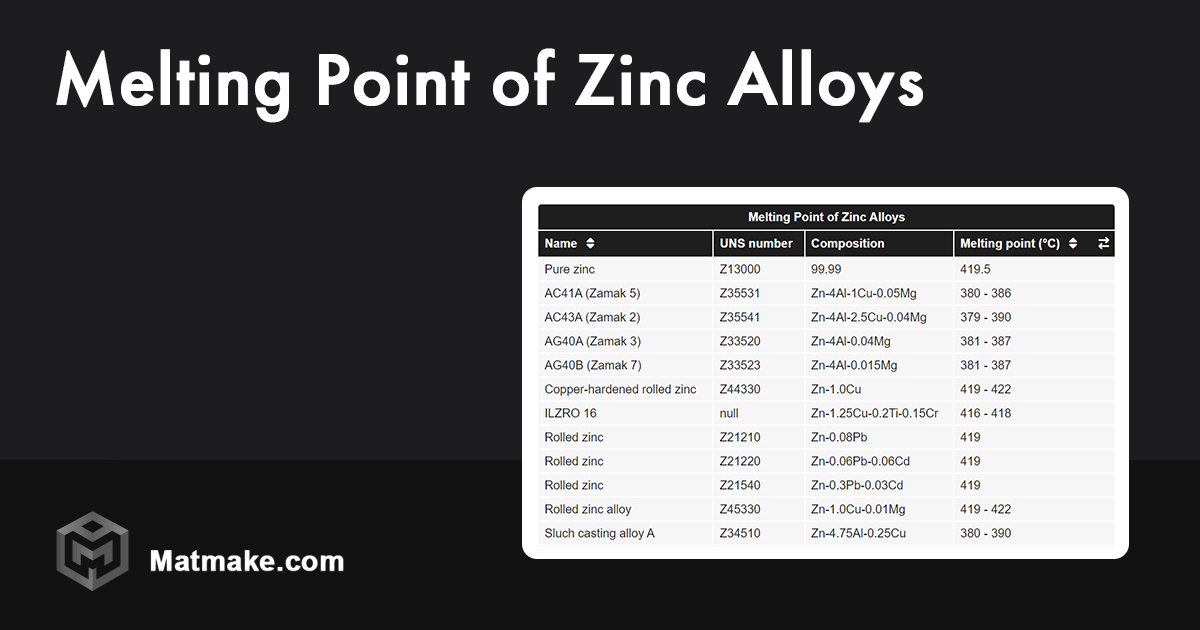

You rarely see pure zinc used in structural engineering. Usually, it's mixed with aluminum, magnesium, or copper. These are the "Zamak" alloys. When you add these other elements, the melting temperature of zinc actually drops further. This is known as eutectic melting. For example, a common zinc-aluminum alloy might start softening at even lower temperatures, making the casting process even more energy-efficient.

Interestingly, the purity of the zinc changes the result. Special High Grade (SHG) zinc is 99.995% pure. If you have "Prime Western" grade zinc, which has more lead or iron in it, the melting behavior gets "mushy." Instead of a sharp transition at 419.5 °C, it goes through a semi-solid phase. This is annoying for precision casting but sometimes useful for certain soldering applications.

Real-world applications of the low melting point

Think about galvanization. This is the process of dipping steel into a bath of molten zinc to prevent rust. Because the melting temperature of zinc is relatively low, you can keep a massive "kettle" of liquid zinc hot 24/7 without spending an absolute fortune on electricity or gas. The steel gets dunked in, the zinc reacts with the iron to form a series of zinc-iron alloy layers, and then a bright, shiny coating of pure zinc forms on the outside.

🔗 Read more: Unlock iPhone with iCloud: What Most People Get Wrong About Activation Lock

If zinc melted at 1,000 °C, we probably wouldn't have galvanized steel everywhere. It would be too expensive. Our bridges, guardrails, and boat trailers would all be rusting away much faster.

- Precision Die Casting: Used for toys (like Matchbox cars), electronics housings, and automotive parts.

- Sacrificial Anodes: Boat owners bolt chunks of zinc to their engines. Since zinc is more "active" than the steel or aluminum of the boat, it corrodes first. This works best when the zinc is cast into specific shapes, made possible by its easy-to-reach melting point.

- Batteries: The casing of traditional alkaline batteries is actually a zinc can. The manufacturing process relies on the metal's malleability and low-heat processing.

Surprising facts about zinc and heat

Most people think all metals get stronger as they get thicker, but zinc’s relationship with temperature is finicky. Zinc is actually brittle at room temperature. If you hit a piece of zinc with a hammer at 20 °C, it might shatter. But if you heat it up to just 100 °C—well below its melting point—it becomes incredibly malleable. You can roll it into sheets or pull it into wires.

Then, once you cross that 419.5 °C threshold, it becomes a very "thin" liquid. It has low viscosity. This is a fancy way of saying it flows like water, not like maple syrup. This allows it to fill incredibly thin sections of a mold, which is why zinc parts can have such complex, paper-thin walls.

Safety first: The "Boil-Over" risk

One thing amateur blacksmiths often get wrong about the melting temperature of zinc is moisture. Because zinc is often recycled (from old pipes or scrap), it can have "pockets" of moisture or grease. If you drop a wet piece of scrap into a pot of molten zinc at 420 °C, the water turns to steam instantly. Steam expands to 1,600 times its liquid volume. This causes a "steam explosion" that sprays liquid zinc everywhere. Given that it's over 400 degrees, it’ll go through clothing and skin in a heartbeat.

💡 You might also like: iPad 11th Gen Case: What Most People Get Wrong

What to do if you are working with zinc

If you’re planning on melting zinc for a project or studying it for a materials science exam, keep these actionable steps in mind.

First, verify your alloy. If you are using scrap, it’s probably not pure. This means your melting point won't be exactly 419.5 °C. It might be lower, or it might be a range. Use a digital pyrometer with a K-type thermocouple to get an accurate reading. Cheap infrared thermometers often struggle with shiny liquid metal surfaces because of "emissivity" issues—basically, the shine tricks the laser.

Second, ventilation is non-negotiable. Even if you stay well below the boiling point, small amounts of zinc can oxidize. Work outdoors or under a high-CFM fume hood.

Third, pre-heat your molds. If you pour 420 °C zinc into a cold steel mold, the metal will freeze (solidify) too fast, leaving you with "cold shunts" or bubbles in your cast. Heating the mold to around 150-200 °C ensures the zinc flows smoothly into every nook and cranny.

Finally, keep it clean. Zinc dross (the "scum" that floats on top of the molten metal) is mostly zinc oxide. You can reduce this by using a flux like ammonium chloride, which helps the impurities separate so you can skim them off, leaving you with a clean, mirror-like pool of liquid metal.

Zinc might not be as "glamorous" as gold or as "tough" as titanium, but its unique thermal properties—centered right at that 419.5 °C mark—make it one of the most useful elements on the planet. Honestly, without its low melting point, the modern world would look a lot more orange and rusty.

Next Steps for Success:

- Calculate your heat load: Ensure your furnace can reach at least 500 °C to account for heat loss during pouring.

- Source High-Grade Zinc: For the most predictable melting behavior, stick to 99.9% pure ingots rather than mystery scrap.

- Safety Check: Always wear a face shield and leather apron; at 419.5 °C, zinc is thin enough to penetrate standard fabric easily.