You’re cruising down a steep hill, tap the pedal, and feel that familiar bite of friction. Most people never think about what’s happening inside that metal bowl behind their rear wheels. But honestly, the drum brake components diagram is a masterpiece of 19th-century engineering that still holds its own in 2026. While disc brakes get all the glory on sports cars, the humble drum is the unsung hero of the trucking industry and budget-friendly commuters alike. It’s a self-energizing system. That means the harder the shoes press, the more they want to stay pressed. It’s efficient. It’s cheap to manufacture. And if you don't understand how the pieces fit together, you’re looking at a very expensive—and potentially dangerous—repair bill.

The Skeleton of the System: The Backing Plate and Drum

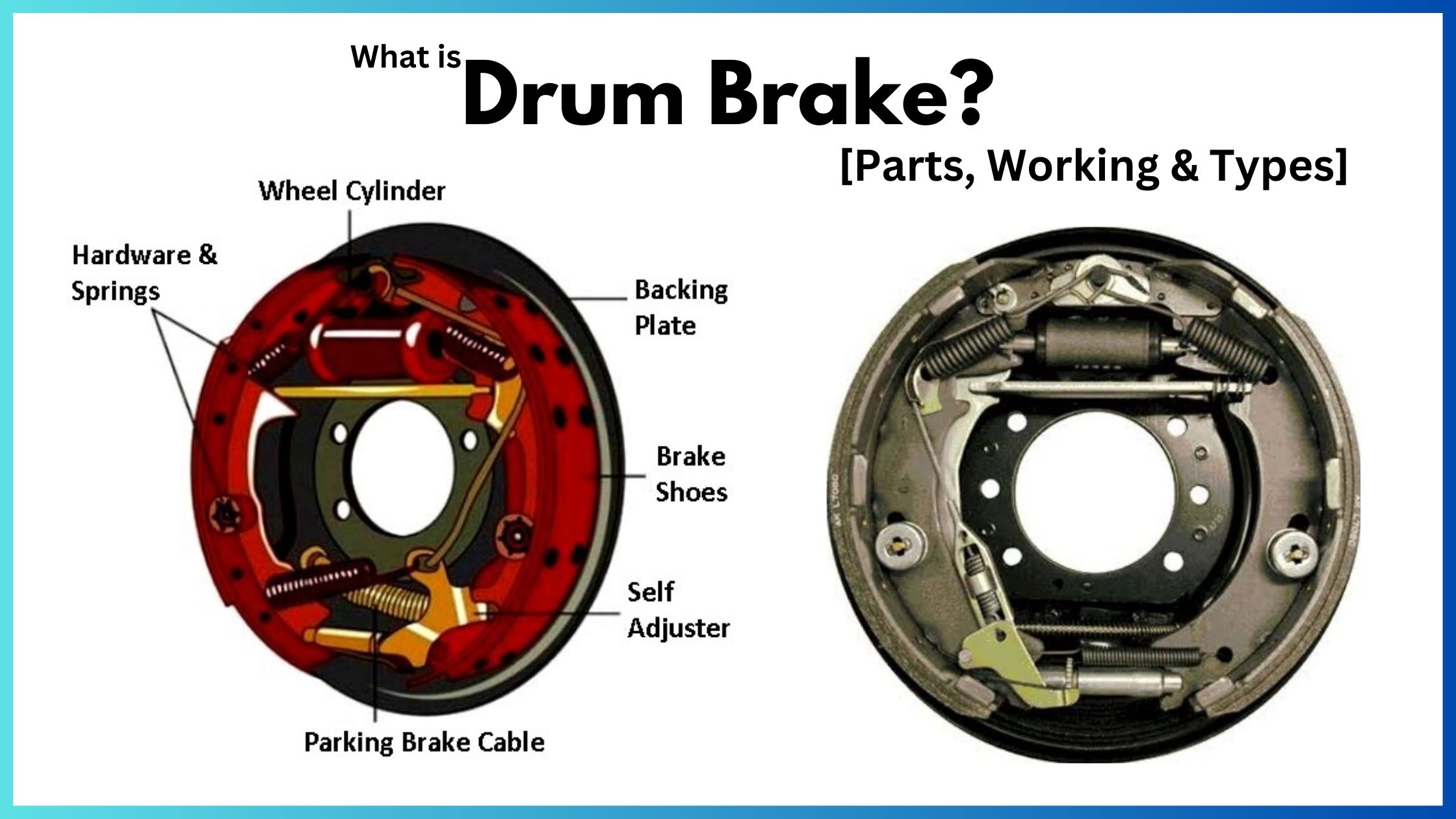

Think of the backing plate as the foundation of a house. Everything bolts to it. If this plate is rusted or warped, the whole system fails. It’s usually a heavy-gauge steel stamping that holds the wheel cylinder, the shoes, and all those pesky springs that like to fly across the garage when you’re trying to fix them. On top of this sits the brake drum itself. The drum rotates with the wheel. When you hit the brakes, the shoes push outward against the inner surface of the drum. This creates friction. Friction creates heat. Lots of it.

Actually, heat is the enemy here. A major drawback often cited by engineers like those at Brembo or Akebono is "brake fade." Because the components are enclosed inside a metal drum, the heat has nowhere to go. If you’re riding your brakes down a mountain pass, that drum expands. Suddenly, the shoes have to travel further to reach the surface. You press the pedal, and... nothing. Or at least, not much. This is why you see massive cooling fins on heavy-duty drum setups. They need to shed that thermal energy or they become useless.

💡 You might also like: Artificial intelligence data annotation: Why your model is only as good as the person labeling it

The Muscle: Wheel Cylinders and Hydraulic Force

Ever wondered how a light tap of your foot turns into enough force to stop a two-ton SUV? It’s all about Pascal’s Principle. Fluid doesn't compress. When you step on the pedal, brake fluid is pushed through the lines into the wheel cylinder. Inside that cylinder sit two pistons. They move outward. These pistons shove the brake shoes against the drum.

The Anatomy of a Leak

You've gotta watch out for those rubber dust boots. If they crack, grit gets into the cylinder. This scores the bore. Then, the fluid leaks out. If you see a wet spot on the inside of your tire, don't ignore it. That’s hydraulic fluid, and once it coats your brake shoes, they’re basically toast. Brake linings are porous; they soak up oil and fluid like a sponge. You can’t just "clean" them with a can of spray. You have to replace them.

The Friction Makers: Shoes and Linings

The brake shoes are the crescent-moon shaped pieces of metal that do the dirty work. They are coated in a high-friction material. In the old days, this was asbestos. We don't do that anymore for obvious reasons. Modern linings are semi-metallic or ceramic.

There is a weird nuance here: leading and trailing shoes. In many drum brake components diagrams, you’ll notice the shoes aren’t identical. The "leading" shoe is pulled into the rotation of the drum, which actually increases the braking force. This is that "self-energizing" effect I mentioned. It’s clever. It uses the car's own momentum to help stop the car. However, this also means the leading shoe wears out faster than the trailing one. If you’re doing a DIY brake job and you swap them by mistake, your braking balance will be completely wonky.

The Chaos of Springs and Adjusters

This is the part that drives mechanics crazy. The "hardware kit." You have return springs, hold-down pins, and the star wheel adjuster.

- Return Springs: These are heavy-duty coils that pull the shoes back away from the drum when you let go of the pedal. If these get weak, your brakes will "drag," killing your fuel economy and overheating the drum.

- The Star Wheel (Self-Adjuster): As the linings wear down, the gap between the shoe and the drum gets bigger. To keep the pedal feeling firm, the star wheel clicks around to push the shoes out slightly. Most of these only work when you're braking in reverse. So, if your pedal feels low, find an empty parking lot and do a few reverse stops. It might just save you a trip to the shop.

The sheer number of small clips and springs is why most experts recommend taking a photo of your specific setup before you pull anything apart. Every manufacturer—be it Ford, Toyota, or GM—has a slightly different way of routing these wires and springs. One wrong hook and the whole thing can bind up.

Why We Haven't Abandoned Drums Yet

You’d think in 2026 we’d all be on carbon ceramics, right? Nope. Drum brakes are incredibly effective as parking brakes. Because of that self-wedge action, they hold a heavy vehicle on a hill much better than a simple disc caliper can. Plus, they are sealed. If you're driving an off-road rig through deep mud, a drum brake keeps most of that grit away from the friction surfaces. Discs are exposed. Mud eats disc pads for breakfast.

Also, cost matters. For the rear wheels of a small car, the braking requirements are minimal—maybe 20% to 30% of the total stopping power. Using a drum saves the manufacturer money, which (theoretically) keeps the car price down for you.

Troubleshooting Common Drum Noises

If your brakes are squealing, it’s usually a "wear indicator" or just plain old brake dust trapped inside the drum. Since the dust has no way to escape, it builds up. Every once in a while, it’s a good idea to have them cleaned out.

- Grinding: Your linings are gone. Metal-on-metal. Stop driving immediately. You're destroying the drum.

- Thumping: This usually means the drum is "out of round." It’s warped. A machinist can sometimes "turn" the drum on a lathe to make it circular again, but if it's too thin, it's scrap metal.

- Chirping: Often a sign that the backing plate needs a tiny bit of high-temp grease where the shoes touch the metal.

Moving Forward With Your Repair

If you're staring at a drum brake components diagram trying to figure out why your car won't stop, start with the basics. Check your fluid levels. Look for leaks at the wheel cylinder. If you decide to dive in and replace the shoes yourself, buy a dedicated "brake spring tool." It costs twenty bucks and will save you three hours of swearing and bruised knuckles.

Always work on one side at a time. That way, if you forget where a spring goes, you can walk around to the other side of the car and look at the assembled version. It’s the ultimate "cheat sheet" that no manual can beat. Once you've got the new shoes on, make sure you manually adjust the star wheel until the drum just barely slides over the shoes with a slight bit of drag. Bleed the air out of the lines—starting from the wheel furthest from the master cylinder—and you're back in business.

Don't overthink it. It's just a set of levers and friction. Keep it clean, keep it lubricated at the contact points, and those drums will probably outlast the rest of the car.

Actionable Next Steps

💡 You might also like: The Big Big Big Black Hole: What We Actually Know About M87\*

Verify your brake fluid condition; if it's tea-colored or darker, it’s absorbed water and needs a flush. Pull your rear wheels and inspect the dust boots on the wheel cylinders for any dampness. If you're replacing hardware, always buy a complete kit rather than reusing old, heat-cycled springs that have lost their tension. For those performing a full rebuild, ensure you use a dedicated brake cleaner to remove the protective oil coating found on new drums before installation to prevent immediate lining contamination.